Cho Chikun: Carrying the Tiger’s Spirit

Cho Chikun (조치훈) is celebrated worldwide for his success as a professional Go player, particularly in Japan, where he studied and achieved professional status as a member of the Nihon Ki-in (Japan Go Association). His bright character and career has made him a legend in the Go community. Watch Cho’s tea-suji — the first of its kind — here.

In 2019, the Japanese government awarded Cho the prestigious Medal with Purple Ribbon, which recognizes individuals for achievements in the arts and athletics. Reflecting on this honor, Cho told the South Korean newspaper Dong-A Ilbo in Korean, “I had a special feeling. I could be even more happy if I could encourage Koreans living in Japan.”

The Legend

Cho Chikun was born in 1956 in Busan, South Korea, as the youngest of seven siblings. Initially named Pung Yeon to match the names of his brothers, the character ‘Yeon’ (연) means ‘‘lotus’ or ‘water lily’ in Korean.

However, a fortune teller told his father, Cho Nam-seok, that keeping the name would lead to his mother’s death while changing it would bring Pung Yeon fame but result in his infant brother’s death. Cho’s father renamed his son to Chikun. The fortune teller’s prophecies came true with the passing of Cho’s infant brother.

Cho’s family was once wealthy. His grandfather was a bank director. During the Korean War (1950-1953), Cho’s father was forced at gunpoint to burn the family’s money.

Discovering Go

Cho does not remember who taught him the game. It was likely his father or grandfather. Cho soon beat his father, grandfather and neighbor’s uncle. After one year, at age 6, Cho was already a 5 Dan in South Korea.

At the time, Japan dominated the Go world.

Japan’s Edo Period (1603-1868) saw the rise of hereditary Go schools that competed for the honor of playing Go before the Shogun at Edo Castle. According to the International Go Federation, “State support of Go, in the form of stipends for professional players, made possible great advances in the level of Go skills and theory during the Edo Period, and this laid the basis for the modern prosperity of the game.” In 1924, the establishment of the Nihon Ki-in spurred the game’s popularity among professional and amateur players.

According to an article from The Japan News, one of Cho’s older brothers had gone to Japan to study Go, where he was astounded by the disparity in skill levels between Japanese and Korean players. Cho’s older brother encouraged his parents to send Cho to Japan.

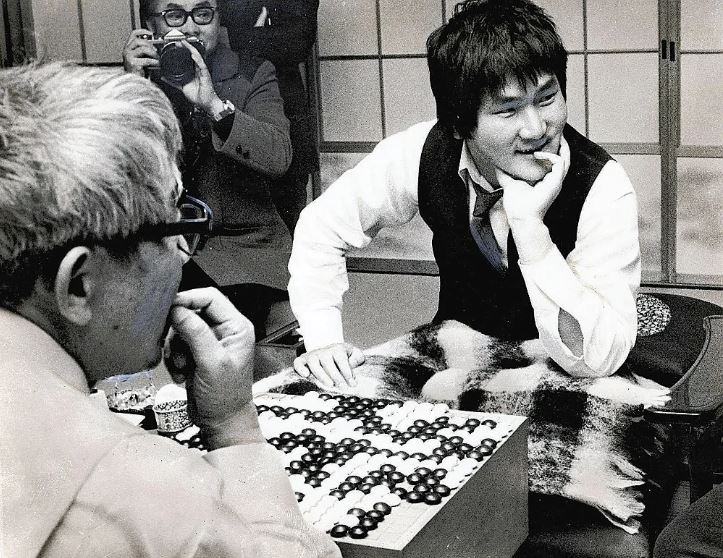

On August 1, 1962, the 6-year-old Cho Chikun landed at Haneda Airport in Japan, accompanied by his uncle Cho Nam-ch’eol and Cho Shoen. He was welcomed by Minoru Kitani 9P, along with his wife Miharu Kitani, their daughter Reiko Kitani and Kitani’s pupil Chizu Kobayashi 6P.

The next day, Cho Chikun played a five-stone game against Taiwanese native Rin Kaiho (Lin Haifeng) 9P, then 6 Dan, who would amass more than 35 titles between the 1960s and 1990s. Cho won the game.

Apprenticeship

Cho spent his first year in Japan as Kitani’s pupil, number 36. The next year, he joined the Nihon Ki-in as a 10 Kyu Go insei (apprentice). In his book Go: A Complete Introduction to the Game, Cho said, “Most apprentices have a teacher, usually a high-ranking professional, who guides them in their Go studies. Every afternoon after school the usual routine for a student is to analyze games with his fellow students or to study Go by himself.”

Despite this structured environment, Cho slacked in his studies. This became more apparent with the arrival of his future friend-rival Koichi Kobayashi, a younger but more diligent student.

Labeled as a ‘trouble-maker’ and ‘difficult,’ Cho faced additional challenges as a Korean in 1960s Japan, a time marked by post-Korean War (1950-1953) discrimination. The Alien Registration Law of 1953 in Japan removed ethnic minorities from their Japanese nationality, limiting their employment opportunities in government and corporations. Koreans could not legally reside in Japan until 1965, and even then, securing rights remained difficult. This context likely impacted Cho’s studies, with some classmates bullying him for his non-Japanese background.

Yet, Cho remained a lively 7-year-old boy, much beloved by Miharu Kitani and others.

That same year, Cho’s mother, Ok-sun, came to Japan to comfort Cho and decided it was time for him to return home. But a tiger painting would keep Cho in Japan.

The Tiger Painting

One day, Cho visited the home of Obayashi-gumi, the executive director of Takeoka Shiro and a wealthy patron of his master. There, Cho noticed a tiger painting hanging on the wall. Shiro offered to let him keep the painting. But Cho’s master intervened, saying that Cho could only have the painting if he became professional by age 10.

This incident motivated Cho to forge ahead.

Four years later, in 1968, Cho became a professional at 11 years and 10 months, setting the record as the youngest-ever professional in Japan. Within a few months, Cho was promoted to 2 Dan. His competitive career looked promising.

The tiger painting embodies Cho’s fortitude in adapting to a new country to achieve his dream. This strength is reflected in his Go. His playing style, centered on territorial control, explodes in creativity.

As Cho said himself, “I try to match strength with strength, lightness with lightness. My ideal is to play in such a way that no one can tell who the player was. There are various elements in my game and it is somewhat chaotic. I have no special preference in the fuseki. And if possible, I’d like to master every style.”

Roaring to the Top

In 1975, Cho achieved his first major tournament milestone. After narrowly missing winning the 22nd Nihon Ki-in Championship to Sakata Eio 9P, Cho bounced back by sweeping the 12th Asahi Professional Top Ten tournament, making him the youngest-ever titleholder in Japan.

Following this milestone, Cho faced another challenge. His mentor and master, Kitani Minoru, passed away on December 19, 1975.

In 1976, Japan’s Go world transformed with the replacement of the Asahi Professional Top Ten tournament by the Kisei and Gosei tournaments, leaving Cho unable to defend his title. Once again, Cho had to be resilient to face his master’s passing and the professional upheaval.

Cho proved himself ready.

In 1983, Cho claimed Japan’s most prestigious Kisei title, making him the first player to hold Japan’s top four titles — Meijin (1980), Honinbo (1981), Judan (1982) and Kisei (1983) — simultaneously.

The Accident

On January 8, 1986, as Cho was getting out of his car, a motorcycle swerved around his blind spot. The motorcyclist managed to avoid Cho’s car but slid and overturned. Cho helped the man up and went to retrieve his motorcycle. Just then, Cho got struck by a vehicle. Cho sustained injuries requiring three months to heal, including a fracture from the knee of his right leg to his ankle, a left-hand fracture and trauma to the head.

Despite his injuries, Cho was determined to defend his Kisei title in his upcoming match against Koichi Kobayashi. Although rivals on the board, they shared profound respect for each other.

From his wheelchair, Cho played well, losing the first match by 2.5 points. Ultimately, he lost his Kisei title, leaving him without a title for the first time in eight years. But not for long.

On July 7, 1986, Cho dominated Otake Hideo 3-0 for the 11th Gosei title.

Staying Strong

Over the decades, Cho continued to excel in his competitive career and make meaningful contributions to the Go community. In 1988, Cho published The Magic of Go, later revised and republished as Go: The Complete Introduction to the Game in 1997. This book covered Go’s basic rules while exploring the game’s relevance to education, history, literature, philosophy and artificial intelligence.

Cho’s competitive spirit remains unwavering despite the rise of younger challenges. A striking example was his performance in the 8th Samsung Cup Finals against rising star Park Yeonghun 9P, known as the ‘Little God of Endgame.’ Cho’s ability to maintain focus under time pressure and use of Park’s attacking weakness led to his hard-fought victory.

While Cho craves winning, his love for his wife Kyoko cannot be beaten. In 2015, Kyoko began losing her battle with pancreatic cancer. Cho forfeited his match to be by her side. “Almost 38 years of married life. She was an irreplaceable wife,” Cho told Dong-A Ilbo, “Whenever I called home after winning or defending a title, she would always say, ‘Well done.’ I feel like I’m striving to hear those words.”

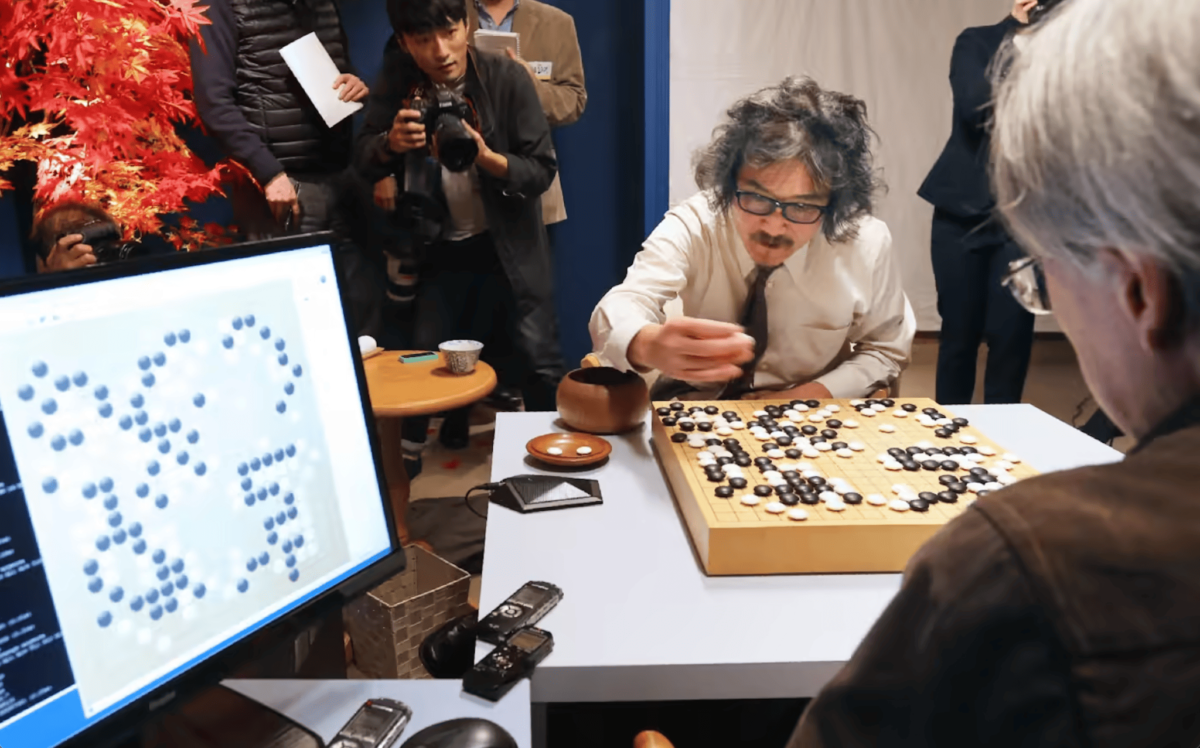

Amid these challenges, Cho continued to make headlines. On November 23, 2016, he defeated artificial intelligence DeepZenGo in a best-of-three series. Both opponents managed to win one game. Cho won the final match, forcing Zen developer Hideki Kato into resignation after 167 moves.

On December 25, 2023, Cho achieved his 1600th win, again breaking the record for the most wins in Go history. This milestone cements his status as a powerhouse in the Go world. Beloved for his wild wit, Cho continues to be a rock of inspiration, showing that we can accomplish anything we set our minds and hearts to.

Оставить комментарий