Finding Go, Finding Community: A Conversation with Devin Fraze

This article is an editorial adaptation of a conversation from the All Things Go podcast, featuring Devin Fraze—an organizer, community builder, and long-time advocate for in-person Go culture.

Rather than focusing on rankings or competitive results, the discussion explores a different side of the game: how people discover Go, why they stay, and what allows a community to survive long after the novelty of learning the rules has faded.

Through stories of chance encounters, long-distance travel, local clubs, and shared spaces, Fraze reflects on Go not simply as a game to be mastered, but as a practice shaped by human connection.

Who Is Devin Fraze

Devin Fraze is a long-time organizer within the North American Go community and one of the people who has consistently worked behind the scenes to create spaces where players can meet, learn, and play together.

Rather than approaching Go primarily through competition, Fraze’s focus has been on connection—helping players find clubs, discover local scenes, and build lasting relationships around the board.

He is the creator of Baduk.Club, a project dedicated to supporting in-person Go culture and making local communities more visible and accessible.

In addition to this, Fraze has been involved in developing a Baduk residency program, an experiment in shared living and study designed to explore what happens when Go becomes part of everyday life rather than a scheduled activity.

In the conversation that follows, Fraze speaks not as a teacher or professional player, but as someone who has spent years observing how people encounter Go—and what determines whether they drift away or choose to stay.

Discovering Go By Accident

Travis: You’ve said you actually stumbled into Go by accident—through a board game. How did that happen?

Devin Fraze: Yeah, that’s exactly right. As a kid I played Reversi on my dad’s computer and thought it was pretty fun. Then as an adult I found this meetup group—humanists who wanted to get together and play board games.

(Many Go players discover the game through Reversi or Othello first. If you’re curious to experience that same starting point, you can try our online Reversi bot here)

Travis: So you show up thinking it’ll be Reversi.

Devin Fraze: Pretty much. I went to the meetup and saw what I thought was Reversi on the table. I said, “Hey, you guys have this game.” And the guy who brought the board was like, “Wait—hold on. You know this game?”

Travis: But it wasn’t actually Reversi.

Devin Fraze: Right. He didn’t even know enough to immediately explain it—he just said it goes by many names, he wasn’t sure. So we started playing, and I’m trying to flip the pieces like Reversi…

Travis: And he’s like: what are you doing?

Devin Fraze: Exactly. I’m like, “Where’s the other color?” And he goes, “You don’t know this game.” So he taught me the actual rules of Go.

Travis: And it clicked right away?

Devin Fraze: It really did. The feel of the stones, the patterns—it just tickled my mind in a special way. And I think I may have even started on 19×19, which is pretty wild.

Travis: That’s a bold start.

Devin Fraze: Yeah—19×19, played a full game, had a great time, no care in the world. And by the end of it, I was hooked.

Hikaru No Go And The Moment It Hooked

Travis: After that first game—what happened next?

Devin Fraze: He mentioned there’s an anime, so I went off and watched Hikaru no Go.

(For many players around the world, Hikaru no Go became a defining gateway into the game. We previously explored the series, its cultural impact, and why it continues to resonate with new generations of players in our article)

Travis: Like a lot of people.

Devin Fraze: Yeah—like many did. And I got super hooked on it, because it felt kind of like Pokémon… but real. That was exciting to me.

Travis: So Go basically escalated fast.

Devin Fraze: It did. Shortly after I learned, I also ended up going on a cross-country bicycle ride—I sold everything, stored a couple books, rode south and west…

A Wandering Go Player

Devin Fraze: I sold almost everything I owned, put a couple of boxes of books into storage, and started riding south and west across the United States.

Travis: That’s a huge life shift.

Devin Fraze: It was. And what’s funny is that Go kind of came with me. Wherever I went, I’d try to find people who played.

At that point, I didn’t really know how to study properly. I didn’t have online resources the way we do now. So the way I learned was by meeting people face to face.

Travis: So Go became part of the journey.

Devin Fraze: Exactly. I’d show up in a city, look for a club, or ask around. Sometimes I’d find strong players, sometimes total beginners. But every place had its own feeling.

It felt a bit like being a wandering samurai—traveling from town to town and learning through encounters. Not through books or theory, but through people.

Travis: That’s a really powerful image.

Devin Fraze: It didn’t feel romantic at the time. It was just how things worked. But looking back, those games shaped how I think about Go more than anything else.

Finding Go Across the World

Travis: As you were traveling and visiting different Go clubs, were there any particular stories that really stayed with you?

Devin Fraze: Yeah — and this one actually became very important to me later.

At the time, there was a website called findgoplayers.com. It doesn’t exist anymore, but back then it was one of the few ways to locate Go players while traveling.

I ended up in Tucson, Arizona, where I stayed with my father for about three months. During that time, I studied Go a lot. There was a strong local player there — a 5-dan — who didn’t know any Japanese, but had trained intensively using spaced repetition to grind tsumego. He was incredibly strong.

There was also a 1-dan who kind of took me under his wing and taught me a lot. And I became friends with another player around my level — his name was Guillermo.

Later on, I continued traveling. I went all the way down to Costa Rica.

Travis: That’s quite a distance.

Devin Fraze: Yeah — and of course, wherever I go, I always try to find Go.

So I used findgoplayers.com again and messaged someone listed in Costa Rica. I wrote something like, “Hi, my name is Devin. I’m traveling through the area and looking to play Go.”

And the reply came back:

“Devin? It’s Guillermo. From Tucson.”

I couldn’t believe it.

We had met years earlier in Arizona — and now, completely by chance, we ran into each other again in Costa Rica, using the same Go-finding website.

He ended up hosting me for about two weeks. We played Go every single day — long sessions, often by the river. We even played a ten-game series together.

That experience really stayed with me. It showed me just how interconnected the Go world can be — and how meaningful it is when players are actually able to find one another.

The Birth of Baduk.Club

source: https://baduk.news/

Travis: At some point, you realized how powerful it was to be able to find Go players while traveling — and that this ability was slowly disappearing. Is that what led you to create Baduk.Club?

Devin Fraze: Yes, very much so.

What really moved me was the experience of being able to find players around the world — sometimes through Google, sometimes through findgoplayers.com. But both approaches had serious problems.

With Google, it was never clear whether the information was actually up to date. You’d find a club listed somewhere, but you had no idea if it still existed. You might dig deeper and see a Facebook page where the last post was from three years ago — and then you’d think, “Okay, this is probably not active anymore.”

Other times, there was no information at all about when anything had last been updated. That uncertainty always bothered me.

And then findgoplayers.com shut down entirely.

I was really sad to see it go, so I reached out to the original developer. I asked him what had happened, and he explained that there were ongoing costs to keep the site running, and constant time spent fixing bugs. He simply didn’t want to manage it anymore.

I asked if he would be willing to share the code — and he did.

The problem was that it was written in Ruby on Rails, a language I didn’t know at all.

So I spent quite a while trying to find volunteers — someone who already knew Ruby and could help get the site back online. But I couldn’t find anyone willing to take that on. And honestly, that was probably a smart decision on their part, because it would have required a lot of work.

At that point, I made a decision that was maybe a little foolish.

I told myself: I don’t care how hard this is going to be. I don’t care what the costs are. I want to create a website that allows people to find clubs and players — and, importantly, lets them know which information is actually up to date.

That was really the birth of the idea.

I initially founded the project with my wife’s brother. He had some coding experience, but he wasn’t a Go player, and he burned out fairly quickly. So eventually, I had to learn everything on my own and rebuild the site myself.

That’s the version that exists today.

I’ve been working on it like that for more than four years now — maybe even five.

Go as Philosophy, Not Religion

Travis: In an earlier interview, you mentioned that Go connects for you with certain philosophical ideas, particularly some concepts found in Buddhist thought. Professor William Cobb, for example, has written extensively about these parallels. What aspects of that philosophy resonate most strongly with you?

Devin Fraze: Professor Cobb’s writings were actually some of the first Go-related texts I ever read. I also came across some of his essays published in Buddhist journals, and I found them deeply inspiring.

I wouldn’t describe myself as a religious person. I was at one point, but I’m not anymore. Still, I want to live a meaningful life — a philosophical life. And Go has genuinely helped enrich that for me.

Part of it comes from how different Go feels compared to the traditional Western mindset around games. Chess is probably the clearest contrast.

In chess, you start with a board full of pieces, and the game progresses through capture and destruction. You remove pieces until one side dominates the other.

In Go, the board starts empty.

You begin with nothing — almost like a beginner’s mind. And instead of destroying, you build. You create shapes, influence, relationships, until the game slowly reaches equilibrium.

That difference felt very meaningful to me. It carried a distinctly Eastern way of thinking.

(The connection between Go and Buddhist thought has been explored by many players and scholars over the years. We looked more closely at these philosophical parallels — including ideas of emptiness, balance, and non-attachment — in our article)

Another contrast is hierarchy. In chess, certain pieces matter more than others. Kings and queens are powerful; pawns are expendable.

In Go, every stone is equal.

A stone might be important in a particular situation, but that importance is contextual — and often imagined. Players will sometimes cling to a single stone, thinking, “This is my stone, I must save it,” even when doing so makes no sense.

Go constantly reminds you that what matters is not the individual piece, but how stones connect.

It’s a collective game.

Travis: That idea of connection comes up again and again in how you talk about Go.

Devin Fraze: Yes — and it also shows up in the practice itself.

I can’t say I’m a very good Buddhist, but the closest thing I have to meditation is deeply concentrating while playing Go.

When I sit down at the board, it becomes a mirror. I’m not really playing my opponent. I’m asking myself: what is the best game I can play today?

How do I avoid greed?

How do I avoid fear?

How do I let go of positions I feel emotionally attached to?

When I’m able to do that — when I find truth on the board — I play good Go. And even if I lose, I still feel good about the game.

But when I give in to those less noble parts of myself, that’s when things fall apart.

As you approach dan level, this becomes even more important. Of course you still need reading skill, life-and-death practice, technical knowledge — but understanding yourself, and how you react emotionally, becomes critical.

The Baduk Residency Idea

Travis: You’ve talked a lot about community in a theoretical sense — but at some point you decided to make that idea very literal. Can you tell us how the Baduk Residency came to be?

Devin Fraze: During my bicycle journey, I ended up living for a while in a commune called Twin Oaks. It’s one of the longest-running communes in the United States, with around a hundred people living there.

It was a really magical place. That experience deeply shaped my understanding of the power of community — what it means to live with others intentionally, to connect more deeply instead of just passing by one another.

I’ve carried that idea with me ever since.

For a long time, in the house that I own, I rented out rooms to people in a fairly normal way. But even then, there was always a kind of community focus — thinking about how people interact, how shared living actually works.

Travis: So the idea was already there, just not fully formed yet.

Devin Fraze: Exactly.

At some point, I was driving a friend across the country to her new home. She’s an artist, and during that trip she told me about artist residency programs.

These are places where artists from around the world can apply to live somewhere for a set period of time — maybe two months, maybe six — and during that time they’re given space, time, and sometimes even a stipend, so they can focus entirely on their work.

That idea really stuck with me.

It also made me think about monks in older times — people who would live in a monastery or hermitage, sustaining themselves in simple ways, while devoting their lives to practice.

And I started thinking: Go players can be just as devoted.

So I half-jokingly said, “Maybe this could be like a monk hermitage for Go players.”

My artist friend immediately said, “That sounds a little cult-like.” So we renamed it.

We called it a Go residency.

Travis: That’s probably a wise branding decision.

Devin Fraze: Probably, yeah.

Around that same time, all of my housemates happened to move out. I was standing at a crossroads.

I could either find new tenants and focus on making more money — or, since I had some other sources of income, I could try something completely different.

I decided to go for it.

I chose to open my home to Go players and see if this idea could actually work.

Travis: So you just… did it.

Devin Fraze: Pretty much. I created a website, shared the idea, and people responded with a lot of excitement.

The first session had six people. The second had seven.

Later sessions were smaller — three people, then two — but each time I learned something.

I learned how to communicate expectations better.

What worked.

What didn’t.

What made sense for a residency program — and what didn’t.

It’s been very iterative.

Each group helped shape what the program eventually became.

Giving Back to the Community

Travis: One thing I really appreciated recently was the clarity you shared about what the residency is actually about. It’s not only about studying Go — there’s also a strong expectation of giving back to the community.

Devin Fraze: Yes, and that clarity definitely developed over time.

At the beginning, my approach was much looser. I would say something like: “Come here, study Go, and we’ll figure out together how you can give back.”

But after going through a few iterations of the program, I realized that wasn’t enough.

Go players show up with very different life experiences. We often joke in the community — “oh look, another programmer” — but that’s not the whole picture at all.

There are people from humanities backgrounds, educators, artists, organizers, people with very different skills and ways of thinking.

Because of that, I came to understand that contribution doesn’t have to look the same for everyone.

Travis: But it does need to exist.

Devin Fraze: Exactly.

The residency isn’t meant to be a retreat where someone isolates themselves and only studies Go. It’s not an escape from responsibility.

The idea is that while you’re here learning and practicing, you’re also participating in something larger.

That contribution might take many forms. For some people it could mean teaching beginners. For others, helping organize events, supporting local clubs, creating materials, or helping strengthen community structures in some way.

What matters isn’t what you do — it’s the intention behind it.

Travis: And that connects strongly with your long-standing belief about organizers.

Devin Fraze: Very much so.

I genuinely believe that organizers are the lifeblood of the Go community. People can learn the rules online, but if they never connect with anyone — online or in person — they usually stop playing.

It’s the community that generates deeper, longer-lasting love for Go.

That belief is at the core of the residency.

Over time, I also realized that rank shouldn’t be a strict requirement. You don’t need to be approaching dan level. It really depends on the makeup of the cohort.

What matters more is seriousness of intention — a desire to study sincerely, and a willingness to contribute something meaningful while you’re there.

Media Brings People In — But Doesn’t Keep Them

Travis: When you think about how people in the West usually discover Go today, where do you think that first connection most often happens?

Devin Fraze: For most people, it’s media.

That was certainly true for me. AlphaGo was a huge moment. A lot of people first heard about Go through news coverage, documentaries, or videos explaining what had happened during those matches.

That was the entry point — suddenly Go was everywhere, even outside the usual circles.

Once I became interested, I remember thinking: I really want to find more. Something I could access in English — whether that meant subtitles, dubbing, or just content that helped me understand what this game actually was.

That’s when Hikaru no Go came into play for me.

Travis: That seems to be a common experience for a lot of players.

Devin Fraze: Yeah, very much so.

What Hikaru no Go did especially well was that it didn’t just explain the rules. It showed an entire culture around the game — relationships, rivalries, mentorship, history. It crystallized aspects of Go that I wasn’t even aware existed.

And it made the game feel alive.

That kind of exposure really matters. Media can spark curiosity. It can create that initial emotional connection. It can bring people to the door.

But what I’ve come to realize over time is that it doesn’t necessarily convince them to stay.

You can get someone interested in Go through a documentary, an anime, or a viral moment — but that alone usually isn’t enough to sustain long-term involvement.

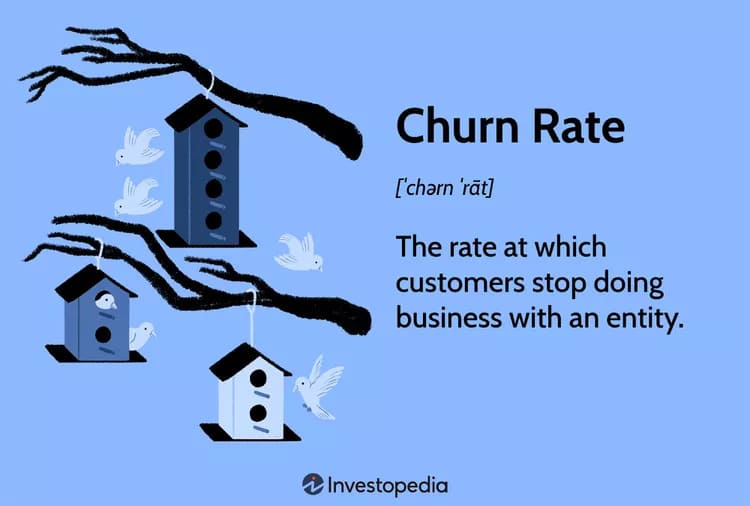

The Data Tells a Hard Truth

Travis: You’ve spent years working as an organizer. When you look at Go through that lens, what do the numbers actually show?

Devin Fraze: What the data shows is that spikes of interest don’t last.

We can see this very clearly with AlphaGo. After those matches, there was an obvious surge of interest. Platforms like OGS saw a large increase in new registrations, and organizations such as the American Go Association experienced growth as well.

For a moment, it really did feel like something big was happening.

But when you look at what happened afterward, the picture becomes much less optimistic.

Within a relatively short period of time, those numbers dropped back down again. In some cases, there was only a very slight long-term increase — and in others, almost none at all.

This isn’t unique to AlphaGo, either.

We’ve seen the same pattern before. Hikaru no Go created a massive wave of interest in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Many players entered the game because of it — and yet, over time, much of that interest faded.

From an organizational standpoint, this pattern is usually described using a term borrowed from business: churn.

Churn refers to the rate at which people leave.

You might successfully bring in new players, but if an equal number leave at the same time, the overall size of the community doesn’t actually grow.

When I looked more closely at the data — especially through my work with the AGA — that’s exactly what I saw happening.

In some years, the organization would gain around five hundred members… and lose roughly five hundred members during that same period.

From the outside, it can look like growth. Internally, it’s deeply concerning.

Because attracting new players is expensive — in time, energy, and resources. And when people leave shortly after joining, all of that effort simply evaporates.

That’s when it becomes clear that the central problem facing Go in the West isn’t awareness.

People are discovering the game.

The real challenge is retention.

If we can’t help players stay — if we can’t help them feel connected and supported — then no wave of interest, no matter how large, will ever be enough on its own.

Community Is the Real Growth Engine

Travis: So if media isn’t the long-term solution, what actually helps Go grow?

Devin Fraze: What really matters is community.

One of the difficult things about Go — especially in the West — is that most players aren’t members of national organizations. They’re not reflected in official numbers. They play online, with friends, or at small local clubs.

In many cases, they’re completely invisible from a data perspective.

That makes it very hard to understand where players actually are, or how healthy local Go communities really might be.

When people talk about growing Go, they often focus on creating the next big wave of interest — the next AlphaGo moment, the next Hikaru no Go. But I don’t think that’s something you can really design or force.

Being realistic, I don’t think we know how to create a tsunami.

And honestly, I don’t think that’s a problem.

There are amazing media creators in the Go world — YouTubers, streamers, bloggers, podcasters. They do important work. They enrich the community, and they make Go more visible.

We also see Go slowly appearing more often in popular culture — showing up in anime, or occasionally in Netflix series. Those moments help raise general awareness, and that’s a good thing.

But none of that is likely to produce a massive, sustained wave of new players on its own.

The real question is what happens after someone arrives.

When a new player shows up at a Go club, do they feel welcomed?

Do they connect with other people?

Do they feel like they belong there?

Because if they do, they’re much more likely to come back.

That’s where I believe the real growth happens.

If we can reduce churn — if we can help people stay engaged once they’ve found Go — then growth begins to take care of itself.

That’s how exponential curves actually work.

You don’t create the wave directly. You create the conditions where people return, again and again — and over time, the community itself becomes the wave.

That’s really what my focus is with Baduk.Club right now.

I’m currently rebuilding the website from the ground up, trying to make it more effective for organizers. I’m also working on new videos and supporting materials — things that can help club organizers keep their players active, happy, and connected.

I don’t expect dramatic overnight results.

But in the same way that rain can slowly turn a mountain into a hill, I believe organizers can make a real impact over time.

Not through hype — but through care.

Closing Reflections

Travis: One thing I remember from an earlier interview you gave is a phrase that really stayed with me. You said that it’s not how your life reflects into Go — but how Go reflects into your life.

Devin Fraze: Yes, that’s still very true for me.

I don’t feel like my life is somehow mirrored in the game. Instead, Go reflects back into how I think about my life.

It gives me a kind of structure — almost like a scaffold — for understanding things. How parts relate to one another. How balance works. How small decisions can influence much larger outcomes.

That way of thinking didn’t come from any single lesson or concept. It emerged slowly, just from spending time with the game.

Travis: So Go becomes a way of seeing.

Devin Fraze: Exactly.

It’s not something I try to explain in grand terms. It’s just that, over time, the patterns you work with on the board start appearing elsewhere too.

That’s probably why I’ve stayed connected to Go for so long.

Оставить комментарий