The First Stones: How to Teach Beginner Go Without Losing the Magic

A guide is for teachers, parents, and club leaders who want to help beginners discover Go without losing their curiosity along the way.

Introduction

It’s a late, slightly dreary afternoon, and the kids at your after-school club are less than thrilled to be stuck at the library learning the rules of Go. They’ve already gotten over their initial bout of freshness and enthusiasm, and are either zoning out or chatting amongst each other. You begin to explain “surrounding territory” and “eyes” too soon, and in a blink you lose them.

I know that feeling (and some of you may too). It’s the moment when Go becomes abstract, distant, an exercise in memorizing instead of discovering that beginners, especially children, lose their spark. That’s why the first, and maybe the most important, lesson I had to internalize as a teacher was: Don’t teach Go too early. Play first. Teach as it fits.

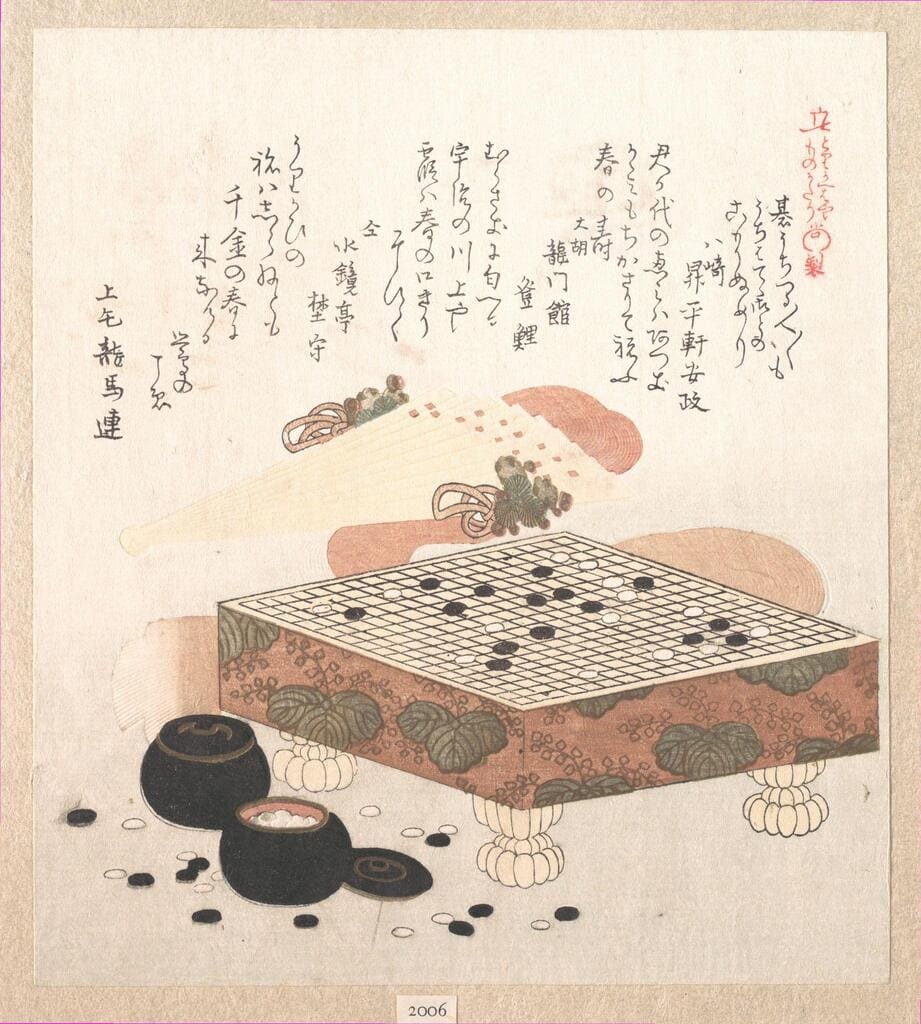

Let the board come alive. Let a stone be a scout or a soldier. Let a group needing two eyes be a fortress that must hold out. When rules arise through the flow, that’s when they truly resonate and will be remembered and implemented.

(Warning: this may lead to a greatly increased amount of fun and excitement, and potentially noise as well.)

In terms of my credentials, I have played Go for over seven years and taught Go consistently for over three years through Go Clubs both at my school and at a local library. These experiences have allowed me to teach Go learners of all ages and develop a system along the way that serves to be the most effective and interesting.

Go is one of those games that looks deceptively simple. Black and white stones, grid lines, and the promise of endless depth. But anyone who has ever tried to introduce the game to a complete beginner knows: teaching Go isn’t always as straightforward as explaining the rules. Beginners, whether they’re children or adults, often get overwhelmed, bored, or confused if you take the wrong approach.

This guide is for teachers, parents, and club leaders who want to help beginners discover Go without losing their curiosity along the way.

Before the First Stone: Setting the Right Expectations

The most important lesson for both teacher and student: beginners don’t need to master Go, they just need to enjoy it enough to keep playing.

New players often assume Go is “deep”, “hard”, reserved for the ‘brilliant’, or that victory is the only sign of success. These expectations can be heavy and dampen curiosity, make mistakes feel shameful, and stifle adventure. From the start, I try to reframe things: No one learns Go in one sitting. You don’t lose anything by experimenting. Making mistakes is part of the journey. If the student leaves a session smiling, asking “When can we play again?” that counts more than remembering all the rules.

The board size can also be part of this expectation game. Presenting a 19×19 too early can make a beginner feel like they’re expected to climb a mountain before even learning how to walk. It may be helpful to start on a smaller board, such as 13×13 or 9×9, allowing for faster feedback and avoids overwhelming the student. Let them taste small victories, learn shape, capture, and tension, then expand outward.

Common Myths and Misconceptions (to Address Early)

Beginners bring all sorts of misconceptions to the table, often reinforced by the game’s mystique. Some believe Go is too hard for children, when in fact kids are often the fastest learners because they spot patterns intuitively. Others think you need to memorize endless openings, when the truth is that experimentation and intuition matter far more. Many assume Go is only about surrounding territory, missing the delicate balance between territory, influence, and life and death. And of course, almost every beginner believes they “should” play on a 19×19 board right away.

If you address these myths early, you save your students a lot of unnecessary frustration. If you are working with children and their often demanding parents, it may also be beneficial to address these concerns with them early on to promote an engaging and fun experience for the child.

Teaching the Rules Simply (and Without Losing Interest)

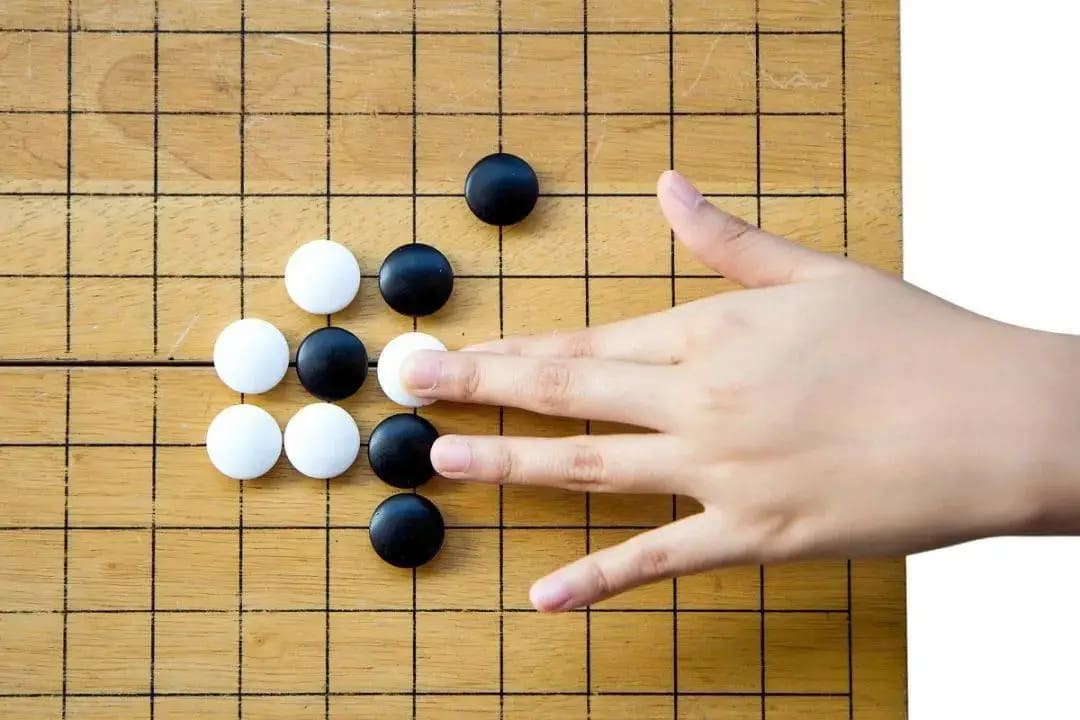

During the first lesson, I’ve developed a system to engage the learners, especially children, without ‘over-loading’ them with information that they may or may not remember. When the time comes to teach rules, do it sparingly, and only when they matter at the moment. Begin with showing how stones can be surrounded and removed. Let them play and stumble—and when they wonder “Why can’t I move there?”, explain liberties and connection, which I often compare to ‘air pockets’ required to live and passageways. With that, the concept of surrounding and capturing comes along with ease. For the very first lesson, keep things light and full of discovery. Start with the capturing game – it’s simple, fast, and fun. When new situations appear, like a Ko or a ladder, pause just long enough to show what’s happening and let curiosity lead the explanation. If a student is struggling with a certain concept, depending on the specific situation (and their reaction to it: simply confused or slightly agitated?), it is up to you to decide whether to continue explaining or move forward.

If your students are more competitive, turn it into a mini round robin tournament to ‘x’ number of captures. If they’re more curious than combative, explore different shapes together: “Can you make a shape that can’t be captured?”

By the second (or next few) meetings, they’ll be ready for a little more structure: show different ways to capture, introduce the ideas of ‘eyes’ as safe places, and maybe finish with a short puzzle or a 9×9 game. Beginners don’t want a lecture—they want to play. The trick is to sneak the rules into the flow of the game.

Later, introduce territory once capturing is familiar. Let eyes and life & death emerge in puzzles or during games, not as definitions from the start. Ko? Only when it appears in their games. Scoring? Use a simple demonstration with one finished board, then revisit later.

It is immensely difficult to explain a particular scenario to someone who has never experienced it before. The power of this method is that rules stop being abstractions and instead become part of the lived experience. They arise out of curiosity and need, not out of obligation.

As a sample first day teaching schedule (that I used just a week before, as I write this article):

- Get to know them. Ask about their expectations, motivations, and connection to Go.

- Give the student a general overview of the game. Answer any questions or concerns they may have.

- Begin with the basics on the 13×13 (or 9×9) board. Introduce the concept of liberties with the singular stone and its four surrounding liberties. Extend to connections and surrounding.

- Start a game of capturing, pausing at points where new concepts and formations arise. Make sure to give the student enough time to think and process.

- After the game, transition to playing with a peer or solving a simple puzzle to strengthen understanding of concepts introduced during the game.

- Repeat as necessary. Get a general idea of the learning style and progress of said student.

- End off the lesson on a positive note. Encourage them to practice on their own as well and introduce resources to them. Answer any questions or concerns they may have.

The Hardest Concepts for Beginners (and How to Make Them Accessible)

Certain ideas consistently trip up new players. Life and death, for example, can feel abstract until shown visually. Influence versus territory is another stumbling block—beginners see secure corners but struggle to appreciate airy frameworks. Sacrifice is perhaps the most counterintuitive lesson of all: that throwing away stones can sometimes lead to victory.

Each of these concepts becomes easier when taught through stories, puzzles, and play, rather than abstract lectures. In my teaching, I generally lean on metaphors (safe houses, ‘air-pockets’/breathing space), visual puzzles, and storytelling (war/battle imagery often works wonders in this sense). Offer one small difficulty at a time, and allow students to fail in low-stakes situations.

For example, when explaining territory, I tell children it’s like building a little garden – you fence it off, but if someone sneaks in and plants their own flower, it’s not yours anymore.

And finally, there is patience. Go moves slowly compared to many modern games, and younger children in particular need encouragement to stick with its deliberate pace. Many players often expect instant progress. Remind them that Go can be a slow game: slow to learn, slow to show significant improvement (especially when one sits at the bottom of the valley of despair). The trick is to keep them engaged and supported in the journey, learning to appreciate not only the ‘destination’. Not sure how? Don’t worry – we’ll open our bag of tricks soon: stories, puzzles, and laughter that make learning feel like play.

How to Teach Different Groups of Beginners

Not all beginners are alike, and the way you teach should reflect that. Teaching a six-year-old is different from teaching a fourteen-year-old or an adult.

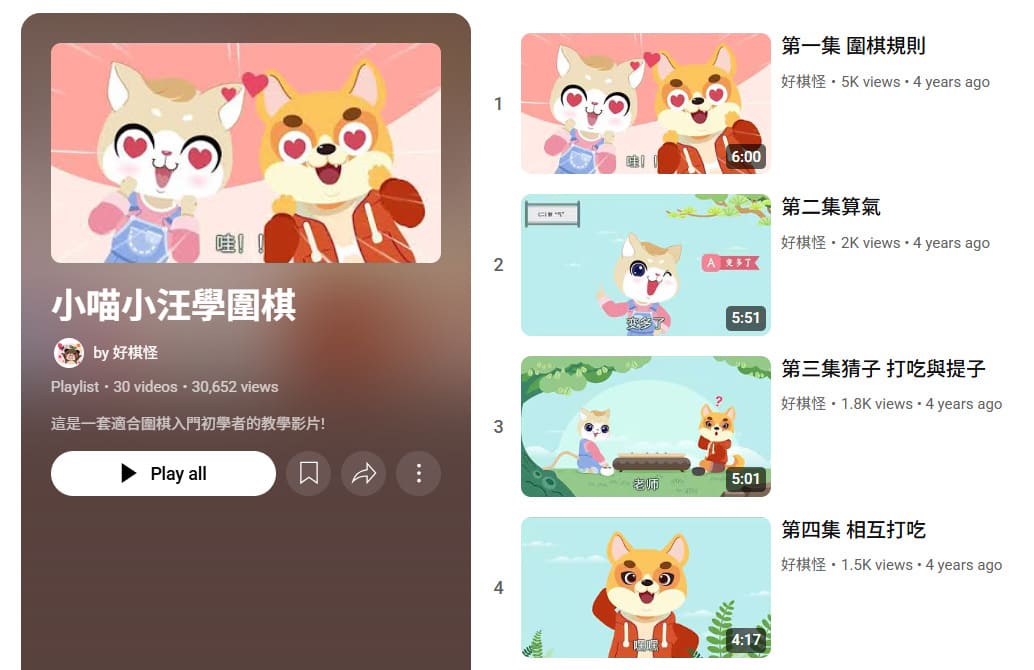

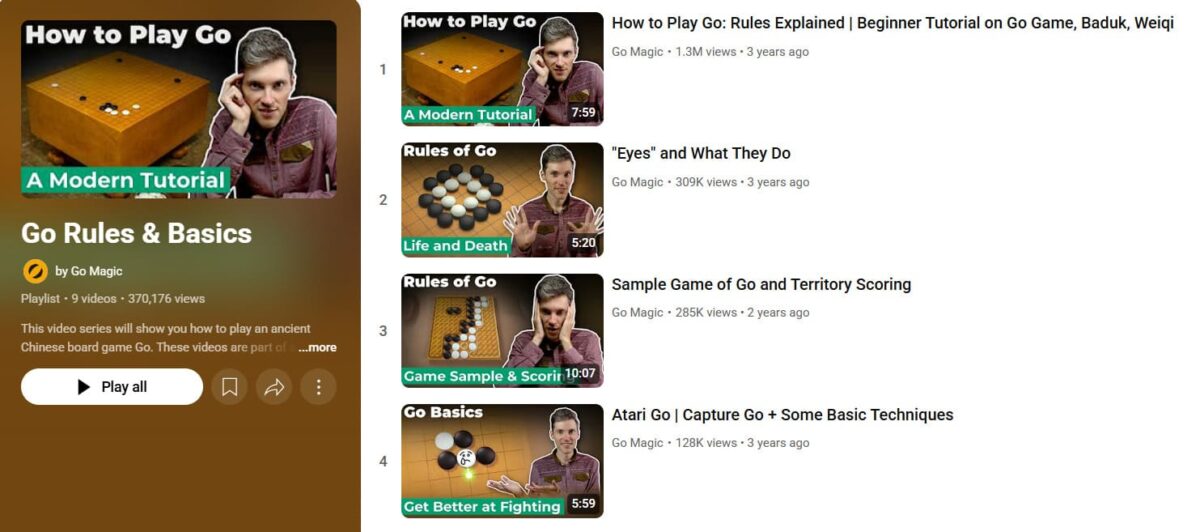

Younger children thrive on stories, characters, and short challenges. Opposing stones can be “armies” that need enough resources to sustain battle and fight for land. Games should be short, playful, and full of small challenges. Keeping in mind their often short attention spans, it is especially important to not let one activity drag on for too long or they may lose interest and no longer keep any new information thrown at them. Some resources I found the most effective are short Youtube videos with recurring characters as teachers, and puzzle-solving websites with timers and graphics.

Teenagers respond better to strategy, competition, and digital tools. For example, letting them “beat the teacher” can be a huge motivator. Some incentivizing can also be helpful, with snacks and prizes working wonders for me, though this depends directly on the specific group you are working with.

Adults often appreciate a logical, direct explanation, along with glimpses into the cultural and historical depth of the game.

And if you’re teaching a mixed group, flexibility is key: vary the board sizes, encourage peer teaching, rotate partners, and create an environment where everyone feels they can experiment and explore, and fail without embarrassment.

Keeping Students Engaged

The most successful Go lessons strike a balance. Rotate between playing games, solving puzzles, and reviewing what just happened. Too much of any one activity, and energy fades. Gamify the learning process: hold ladder races, run capture contests, or give corner-defense challenges. Encourage creativity by letting students try bold, even “bad,” moves—they’ll learn faster from the results than from a lecture.

And always remember to highlight what went right, and whenever possible, praise intention and shape rather than only results. Beginners, especially children, learn better when success is celebrated. Celebrate unexpected discoveries and encourage curiosity–if new ideas arrive during a game it is totally okay to take a pause and test it out.

If a student becomes gloomy after losing their stones, comfort them while also highlighting future improvements: “That’s not a loss – you just found out which fortress walls don’t hold yet. Next time, you’ll know how to build stronger ones.”

Depending on meeting lengths, it can also be helpful to have a break in the middle to conduct team-building activities. A simple game of Simon Says or connect five can not only allow children to let off some steam, but also promote a sense of community.

Tools and Resources

The right tools can make teaching much smoother. Small boards are essential, whether physical or digital. Online platforms and beginner-friendly apps can extend practice outside of lessons. Tsumego puzzles, if chosen carefully, build intuition without overwhelming. And for younger players, stories, manga, and visual Go media can spark a sense of wonder about the game’s world. Some club members cite Hikaru No Go as their entrance or motivator in their Go journey.

As specific examples, I often use Youtube videos to help introduce new concepts (小喵小汪学围棋 for Mandarin speakers, and Go Magic Tutorials for English speakers).

What Not to Do

It’s worth being candid about what not to do.

Be wary of falling into teaching traps. Don’t lead with a lecture on all the rules. Don’t push 19×19 or professional patterns too early. Don’t make early sessions about winning. Don’t drown students in joseki, fuseki, or pro analysis they’re not ready for. And above all—don’t make Go feel like homework. It’s a game, and it should feel like one.

Also watch your own expectations. Teachers often feel pressure for visible progress; but depth evolves slowly. Be patient with your students, and with yourself.

Conclusion

Teaching beginner Go is not primarily about conveying rules or shaping perfect technique. It is about nurturing curiosity, giving space for exploration, and making the board a companion rather than a battleground. If your student walks away excited to play “just one more game” or challenges you next session, you’ve done your job—even if they still confuse territory with influence or forget the ko rule. Go teaches itself, as long as the student keeps playing. Your role is simply to make that first step enjoyable.

So sit with your board. Play. Laugh at blunders. Celebrate surprises. Teach not by telling, but by showing that the stones are alive—and that every move, even a “bad” one, matters. Every beginner places their first stones a little differently. Once curiosity takes root, the board teaches the rest.

Оставить комментарий