Nie Weiping and the Rise of Modern Weiqi

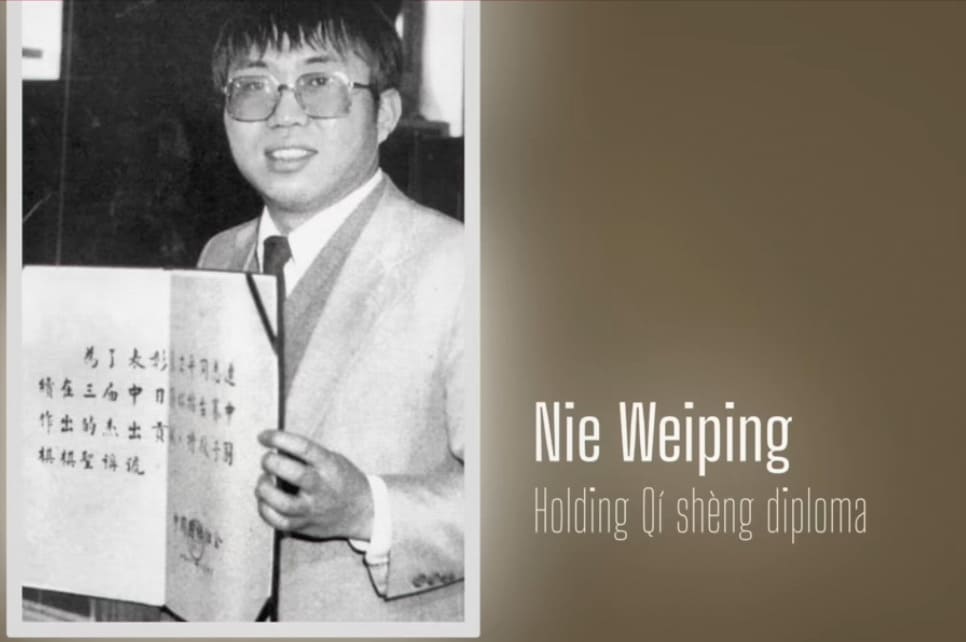

Nie Weiping passed away on January 14, 2026, at the age of 77. And this was not simply the death of a great professional player. For many in China, it felt like the end of an era.

There were other strong players in his time. There were champions, title holders, rising stars. But only one of them became a symbol of national revival.

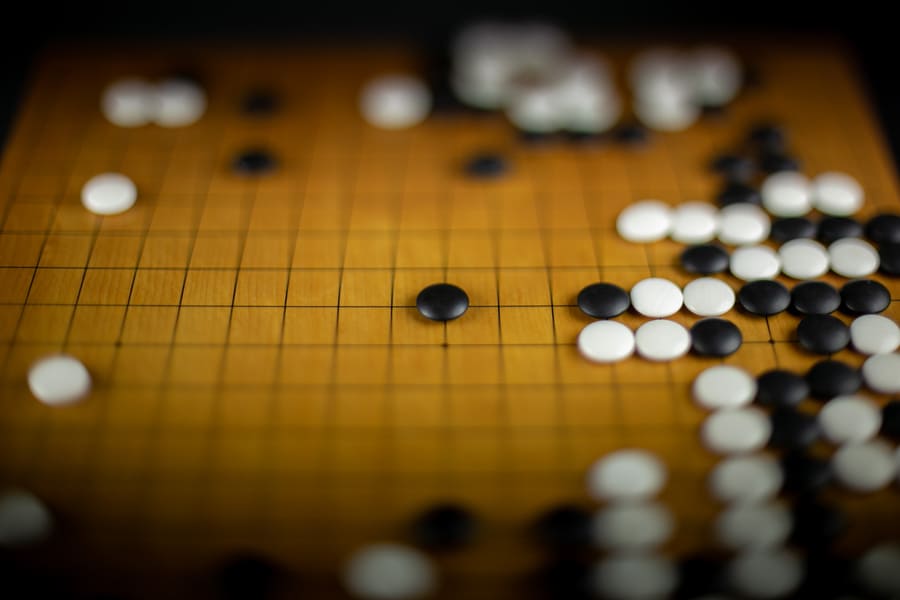

In the late 1970s, China was still rebuilding itself. Go — a game born on Chinese soil — had fallen behind on the international stage. Japan was the unquestioned center of the Go world. If you wanted to become truly strong, you went there. If you wanted to measure yourself, you faced Japanese professionals.

And then came the China–Japan Super Matches.

What happened in those matches was more than a sporting upset. One player — standing alone against the strongest team in the world — changed the course of Chinese Go forever.

This article is adapted from a video on our YouTube channel.

What Does It Mean to Be a “Go Sage”?

To understand why Nie Weiping’s name carries such weight, we have to go back several centuries.

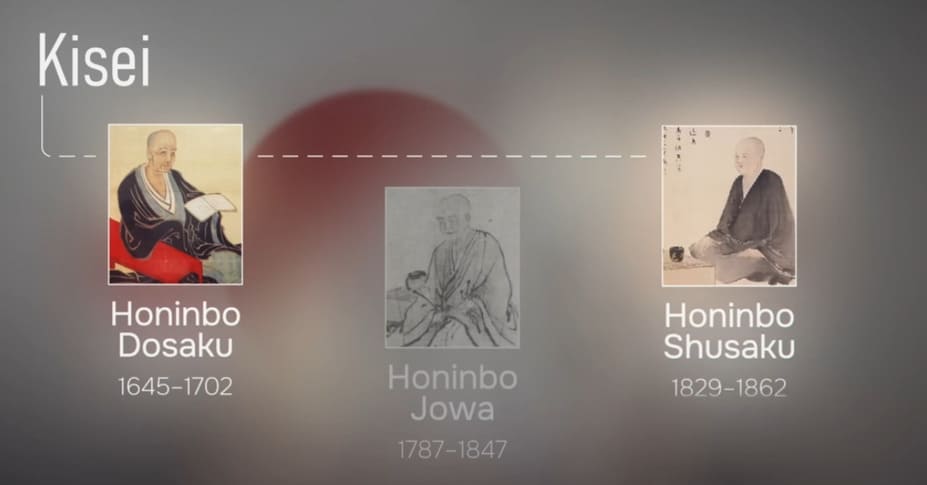

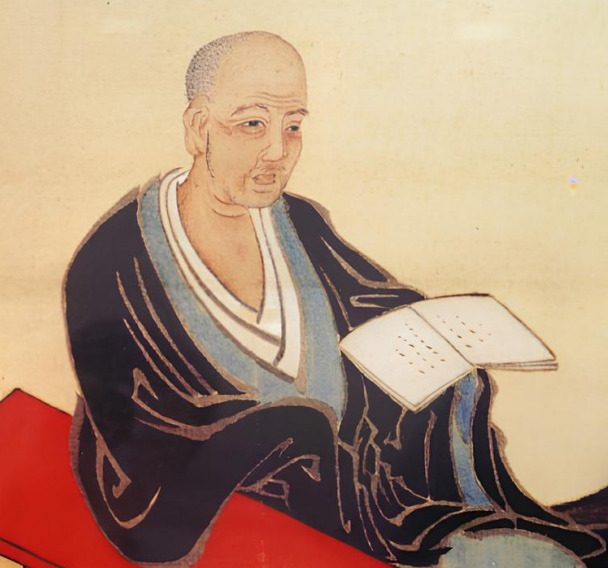

The Japanese Tradition: Kisei

In Japan, there once existed the honorary title Kisei — the “Go Saint” or “Go Sage.” It was not a title you could win by accumulating trophies. It was something bestowed by history, usually after a player’s death, when time itself had confirmed their greatness.

Only two players were ever officially granted that honor: Honinbo Dosaku and Honinbo Jowa. Later, after political intrigue and behind-the-scenes maneuvering, Jowa unofficially lost that distinction, and it was informally passed on to Honinbo Shusaku — another towering figure of the Edo period.

The key point is this: being called a “Go Sage” was not about rating points. It was about cultural impact. It was about becoming larger than the game itself.

The Chinese Tradition: Qisheng

In ancient China, the same concept existed under a different name: Qisheng — also “Go Sage.”

Several legendary players were remembered with that title. Among them were Huang Longshi, and the two great Qing dynasty masters Fan Xiping and Shi Xiangxia. These were figures who defined entire eras of Chinese Go.

But in modern-day China, something remarkable happened.

There was only one person who was called a Go Sage during his lifetime.

That person was Nie Weiping.

How did that become possible? Why in the late 1970s and 1980s — and not earlier?

China After the Cultural Revolution: Rebuilding the Game of Go

By the late 1970s, China was still recovering from the Cultural Revolution. Cultural institutions had been disrupted, traditions interrupted, and Go — one of the oldest games in Chinese history — had suffered along with everything else.

A new generation of young Chinese players was beginning to emerge, trying to revive the game inside the country. And at the head of that wave stood Nie Weiping. He won major domestic tournaments, became a 9-dan, and quickly established himself as the strongest player in China.

But strength inside China was not the same thing as strength in the world.

At that time, Japan was the unquestioned center of global Go. If you wanted to become truly strong, you went to Japan. The best teachers were there. The strongest professionals were there. The highest titles were there.

Even players from other countries followed that path. The Korean master Cho Hun-hyeon studied in Japan under Segoe Kensaku for years. Cho Chikun did the same. And even Go Seigen, born in China, built his legendary career in Japan.

So when the idea of organizing China–Japan Super Matches appeared, the context was clear. From the Japanese perspective, this was expected to be a kind of teaching match. From the Chinese side, the goal was modest: not to lose too badly.

That was the atmosphere going into the first Super Match.

China was not yet seen as an equal. It was seen as a challenger — and not a very dangerous one.

And that is precisely why what happened next mattered so much.

The First China–Japan Super Match (1984–1985): A Turning Point

Even the name of the match revealed what was at stake.

In Japan, it was called 日中スーパー囲碁 (Nicchū Sūpā Igo) — literally “Japan–China Super Go.” The first character, 日, stands for Japan, the “Sun.” The second, 中, stands for China, the “Middle Kingdom.” Japan came first.

In China, the very same match was called 中日围棋擂台赛 (Zhōng-Rì Wéiqí Léitáisài) — “China–Japan Weiqi Challenge Match.” The same two characters, 中 and 日, but reversed. China first, Japan second.

Each country, naturally, placed itself at the front.

But on the board, the hierarchy seemed clear.

From the Japanese perspective, this was expected to be something close to a teaching match. Japan was the mecca of Go. The strongest titles were there. The deepest theory was there. The most experienced professionals were there. The idea that China could truly challenge that dominance did not seem realistic.

And the beginning of the first Super Match appeared to confirm those expectations.

Kobayashi Koichi, one of the greatest Japanese masters of the time, defeated six Chinese players in a row. One after another, they fell. The Chinese team was collapsing.

Until only one player remained.

That player was Nie Weiping.

There is a story — perhaps half legend, perhaps entirely true — that Kobayashi was so confident of victory that he declared he would shave his head if he lost to Nie Weiping.

He ended up shaving his head.

The culmination came in their game — a long, balanced struggle that would turn into one of the most beautiful and dramatic ko fights in modern Go.

The Game That Turned the Match

What followed was not a quick collapse. It was not a blunder. It was a long, tense struggle that stretched close to 200 moves. The position remained balanced. Both sides had territory. Both sides had weaknesses. And then, almost quietly, the ko fight began.

Usually, a ko fight is arithmetic. You count the stakes. You compare threats. You decide whether it is worth it.

But sometimes — very rarely — a ko becomes art.

In this game, Nie Weiping, playing Black, was risking seven stones. Kobayashi, playing White, was risking only one. On paper, that already looked dangerous. At some point, Black would have to connect. At some point, the fight should end.

And yet, it didn’t.

White chose to take profit in the center.

From a distance, it looked reasonable. White gained solid points. The center was becoming tangible territory. The ko did not seem urgent anymore.

But Nie Weiping was not playing only the visible position. He was playing the hidden one.

Instead of ending the fight, he found a ko threat that did not even look like a ko threat. A move that turned a corner into a life-and-death problem. If White ignored it, disaster would follow. If White answered, the ko would continue — but now on Black’s terms.

The tension shifted.

Then came the moment that truly broke the balance.

A fearless invasion on the first line.

At this stage of the game, such a move feels almost humiliating. Crawling along the first line is something we associate with desperation. With small gains. With endgame reductions.

But here, it was neither small nor desperate.

This invasion unlocked everything. It threatened connections. It created squeezes. It turned previously safe white territory into a fragile shell. Variations branched out in every direction. If White blocked one way, stones would collapse somewhere else. If White defended locally, Black would break through globally.

What looked like a reduction became demolition.

And finally, after all the exchanges, after the ko threats and counter-threats, after the invasion had done its damage, came the quiet move that sealed it.

Not flashy. Not dramatic.

Just precise.

Black secured the left side, played the bigger endgame points first, and only then connected what needed to be connected. A masterclass in priorities. When the dust settled, Black was ahead by four points.

Four points.

Just one “innocent-looking” ko fight in the late game — and the entire match had turned.

If you would like to see the full move-by-move breakdown of this extraordinary ko fight, you can watch our detailed analysis here:

The Iron Gatekeeper

After defeating Kobayashi Koichi, the story did not end.

Two of the strongest Japanese players were still waiting: Kato Masao and Fujisawa Shuko. If the first victory had been dramatic, what followed was decisive. Nie Weiping defeated them both and secured the overall victory for China in the first China–Japan Super Match.

Today, it is difficult to imagine what that meant.

People gathered around radios to listen to the moves as they were relayed. Spontaneous celebrations broke out in the streets. This was not simply about winning a game. It was about proving that Chinese professionals were once again world-class. It was about bringing the entire country back into the game of Go.

The following year, another Super Match was organized. And once again, Nie Weiping found himself as the last remaining member of the Chinese team.

He won five games in a row.

He defeated Yamashiro Hiroshi. He defeated Takemiya Masaki. He defeated Otake Hideo in the final.

And the year after that, he did it again.

In the first three Super Matches, Nie Weiping achieved eleven consecutive victories — and added one more in the fourth. That streak earned him a nickname that perfectly captured his role: “The Iron Gatekeeper.”

He was not just the strongest Chinese player of his time. He became the reason millions of children in China began to take Go seriously again. The game was no longer a relic of the past. It was alive, competitive, and capable of standing on equal footing with the world.

Years later, he founded a Go school that helped shape the next generation. Among its students were Chang Hao, Gu Li, and even Ke Jie. Modern Chinese dominance in international Go did not appear out of nowhere. It grew from a revival that had a face — and that face was Nie Weiping.

There were many talented players in China during that era.

But it is Nie Weiping who will always be remembered as the man who started the revolution.

That is why his name remains a household name in China.

Rest in peace, Nie Weiping 老师.

Оставить комментарий