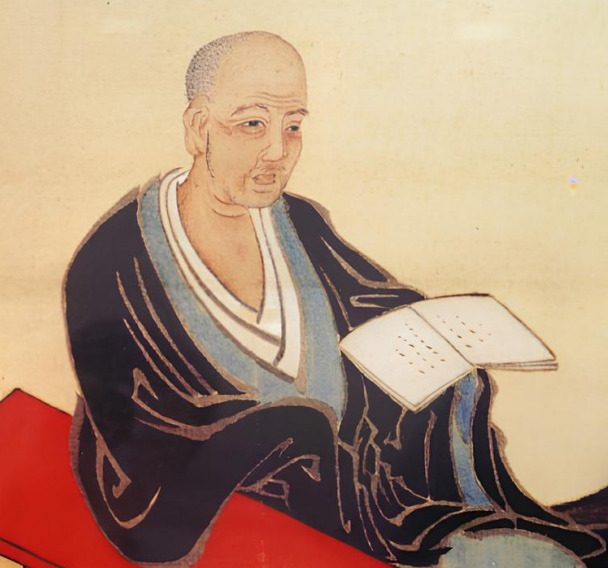

Honinbo Shusai: The Twilight of an Emperor

(photo source: Sensei’s Library )

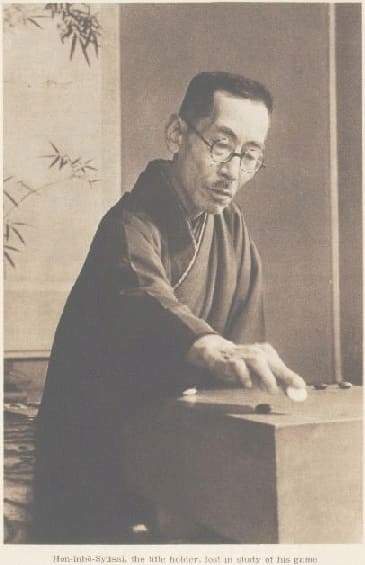

More than for his brilliant moves on the goban, Honinbo Shusai is remembered for what he represented: the end of an era. He was the last holder of the Honinbo title by inheritance, ensuring that the title could be earned through merit rather than passed down by inheritance, adding even greater value to the game. During his career, as he faced younger players, he showcased a new face of Go: faster and more competitive, yet far removed from the traditional values of the past. This is where Honinbo Shusai becomes immortal, representing the bridge between the old and the new world.

The Origins of Honor

Born in 1874 as Kobayashi Torajirō, Shusai spent his childhood in a Japan still tied to feudal legacies. It was a time when Go was not simply a sport or discipline, but an art preserved by master families, the Go Iemoto, where knowledge was passed down like a noble inheritance.

The young Torajirō was adopted by the prestigious Honinbo family, thus becoming Honinbo Shusai. More than a choice based on merit, it was a consecration: the last representative of the school founded by Honinbo Sansa in the 17th century. An honor, but also a burden: from that moment on, his name and life would be inseparable from the history of Japanese Go.

Master by Title

In 1907, Honinbo Shusai became the 21st and final hereditary head of the Honinbo school. The “Honinbo” name was not gained as a result of competition but inherited following a Japanese cultural transmission model in which power and knowledge passed within a school. The title was granted not necessarily to the finest player, but to the player best qualified to hold up the dignity of the school and to have control over it, guiding its students.

Shusai also held the highly honored title of Meijin (名人, “master” or “person of eminence”) Like the Honinbo title, the Meijin title was largely honorific, given by consensus and reputation rather than by formal competition. As Meijin, Shusai was granted several ceremonial privileges during official matches, including the right to choose his playing color, which was a significant advantage at the time.

But this system began to feel outdated. A new generation of players, including Go Seigen and Kitani Minoru, viewed Go as a science and called for a more competitive, merit-based system. The idea of a “master by title”, honor given by birth and respect rather than pure skill, was questioned.

The Style of the Meijin

Shusai was known for his slow and methodical approach to Go, a style that allowed him to deeply analyze each position before making his move. His strength lay in his ability to fight and read the game, honed through years of playing handicap games against stronger opponents, giving him a unique advantage, as he developed a keen understanding of the nuances of balance and positioning. When playing as White, Shusai often made longer and looser extensions, which might have seemed less compact than those of others, but they covered weak spots more evenly, allowing him to maintain a strong position over time.

The introduction of new ideas from other regions, particularly China and Korea, made his style appear outdated in comparison. Players like Shuei, with their more elegant and refined approach, were preferred over Shusai’s more forceful and methodical tactics. One aphorism from that time suggested that:

Players should aim to play Black like Shusaku, White like Shuei, and, for handicap games, White like Shusai.

Though criticized by younger players for being too conservative, Shusai’s style was grounded in a deep respect for tradition. For him, Go was a form of dialogue, not a mere contest of strength. His technique was inseparable from his worldview, focused not just on winning, but on honoring the history of the game with each move. In his best moments, Shusai played with the patience of a monk and the precision of a surgeon. Time was not an obstacle for him; rather, it was a tool, seamlessly integrated into his play.

The Legend of the Game Against Go Seigen

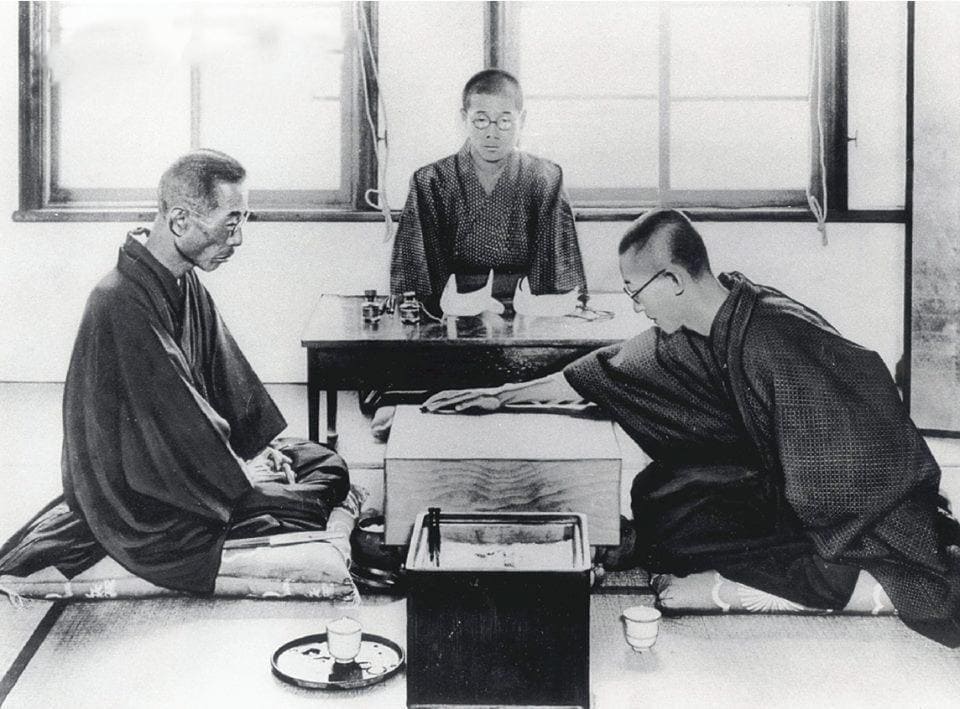

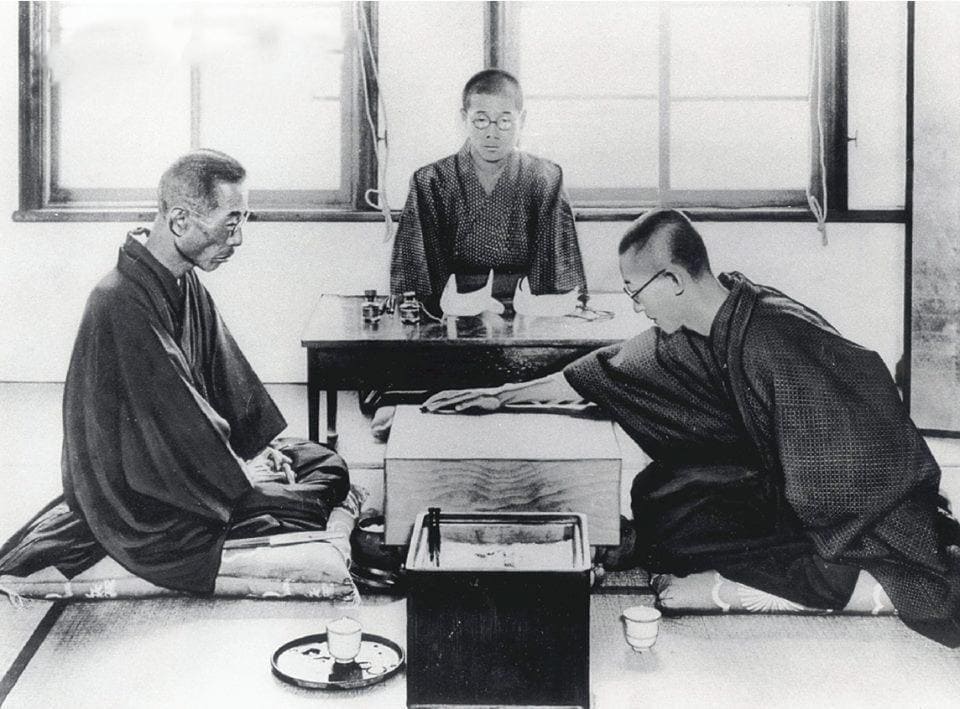

In 1933, “the Game of the Century” took place, when the Meijin was challenged by a young prodigy, just nineteen years old, named Go Seigen, already famous for his innovative and bold playing style. The game lasted six months with long breaks between moves, giving a significant advantage to the challenged Shusai, allowing him to consult with his disciples. In fact, according to some reconstructions, many of his best moves in that game were the result of collective analysis, rather than purely personal genius.

Photo sourced from:Go Seigen vs Honinbo Shusai, 1933

The highlight (and most debated) moment of the game is move 160: a brilliant sequence that shifts the balance of the game and leads Shusai to victory. There were rumors suggesting that the move was actually made by one of his students rather than Shūsai himself.

The game became legendary. But rather than glorifying Shusai, it contributed to consolidating the fame of Go Seigen, whose attacking style had put an entire school of thought in serious difficulty.

The Slow Decline

In the years following his peak, Shusai’s role in the Go world became more symbolic than skill-based. Though he still won games, his victories became harder to achieve. His moves, once sharp and quick, grew slower and more deliberate, reflecting a time that was slipping away. Younger players began to lead the game in aggressive directions, while Shusai’s careful, traditional style started to feel out of place.

In 1936, he decided to give up the Honinbo title to Japan’s official Go organization Nihon Ki-in. It was an important decision that ended the old system in which the title had been passed down through family ties, helping to turn it into a prize earned through skill. It was a quiet but powerful moment—the close of one era and the beginning of another.

Though his playing power had waned, Shusai’s legacy endured as a symbol of Go’s traditional roots, even as the game evolved around him.

The End of an Era

Shusai passed away in 1940, just as modern Go was beginning to take shape. His legacy was more spiritual than technical: although he was not the strongest player of his time, he was the bridge between two worlds.

Many criticized him for the ambiguities in his style and the privileges of his position. Others celebrate him for the composure and dignity with which he guided the transition to a new era.

“Shusai was not just a player. He was a living ritual.”

-Go Seigen

The Master of Go

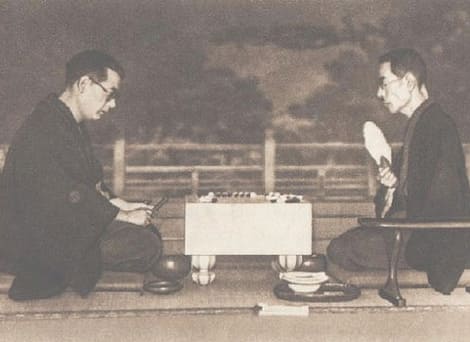

Ten years after Shusai’s death, in 1954, the famous writer Kawabata Yasunari published The Master of Go, which tells the story of the final game played by Honinbo Shusai—fictionalized as ‘the Master’—against the young challenger Otaké, a literary representation of Kitani Minoru.

Photo sourced from: The Japan Times

But it is not just a game. Kawabata uses the encounter to depict the decline of an ancient world and the rise of the modern one: on one side, the elderly Master, a symbol of ritual and hierarchy; on the other, the new competitive Go, ruthless, logical, almost impatient.

The book highlights the tragic dimension of Shusai: no longer simply the arbiter of generational transition, but a man struggling with time itself. His desire to control every detail (from the schedule to the pauses, from the press to the ceremony) takes on almost obsessive contours. It is not difficult to read into this the drama of someone who, despite knowing they must step aside, struggles to accept their exit.

Kawabata, who personally witnessed the game, does not judge him. In fact, he portrays the Master with a melancholic delicacy, restoring to him that fragile nobility which escapes technical accounts. In a memorable passage, he writes:

“The Master seemed to suffer with every stone played, as if each one took something away from his soul.”

More than a book about Go, The Master of Go is a book about endings. The end of a career, of an era, and of a way of understanding beauty. It is through these pages that Honinbo Shusai perhaps found his deepest immortality: not as the strongest, but as the last of a lost lineage.

The Legacy of Honinbo Shusai

Today, when the Honinbo title is awarded every year through intense challenges between the best in Japan, Shusai’s name survives as the last guardian of a vanished era, the echo of a Go that was also ceremony, status, and theater.

And perhaps, in the silence of his slow and reflective games, something of that mystery still survives.

Is there something in his way of understanding the game that you think we’ve lost?

Оставить комментарий