The Story of AlphaGo: How AI Conquered the Hardest Board Game

Every game seems to meet the same fate: as computers improve, they overtake us, from Chinook over Marion Tinsley in checkers (1994) to Deep Blue over Garry Kasparov in chess (1997).

Go looked immune: its branching factor made brute force collapse, and for years Go programs were far weaker than strong humans.

Less than twenty years after Deep Blue, in 2015, DeepMind unveiled AlphaGo, and within a year it had upended those assumptions, forcing a rethink of “intuition” and “creativity” in Go.

That was the threshold where Go’s final frontier became AI’s proving ground.

This article is adapted from our Go Magic channel video.

Why Go Is Different

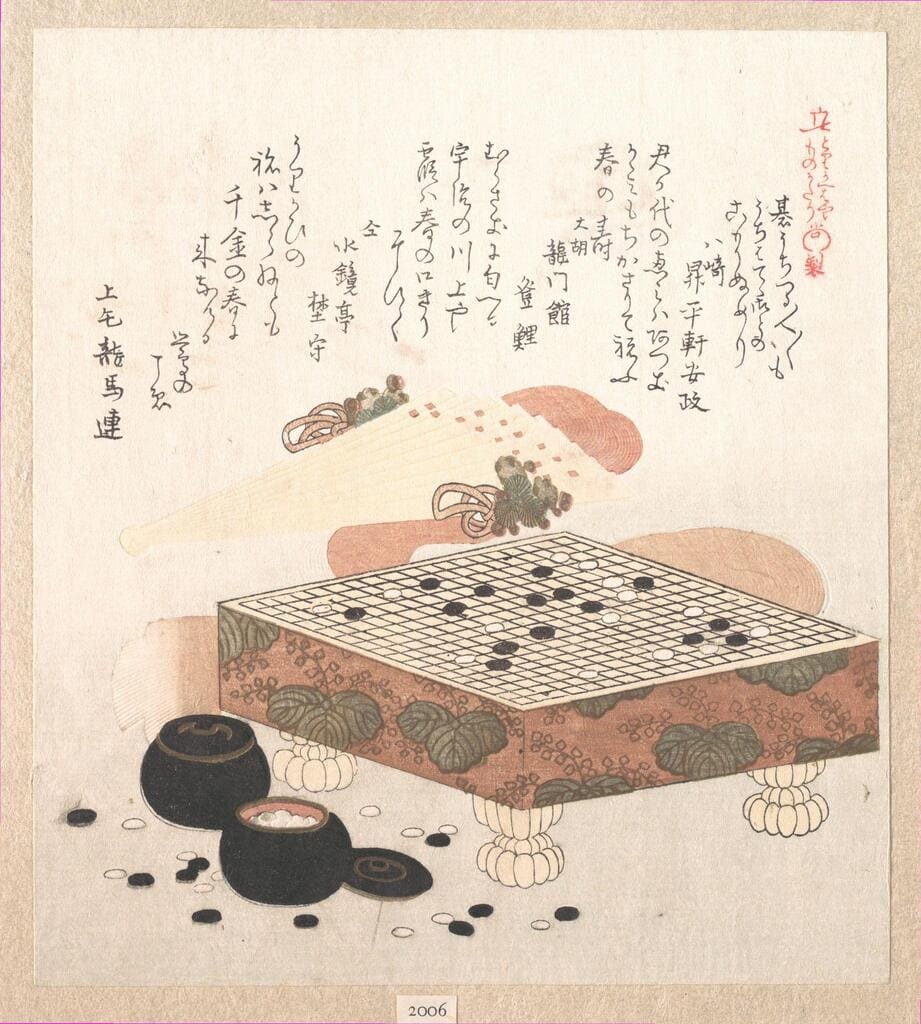

Before AI enters the picture, the game itself deserves a quick frame. Go pairs rules simple enough to explain in a minute with positions that spiral into surprise and uncertainty, a combination that long kept computers far behind strong humans.

Simple Rules, Unbounded Complexity

Players place black and white stones on empty intersections; Black plays first, White replies, and turns alternate. The aim is to divide the board into areas of secure territory, with captures as a means rather than the goal. A stone’s liberties are its adjacent intersections; remove them all and the stone is taken off the board. In a basic example, a lone white stone has four adjacent intersections; once Black occupies all four, the stone is captured. From that tiny ruleset, the game’s decision tree quickly outgrows straightforward calculation. For a deeper, step by step introduction to the rules, see our interactive guide.

Earlier Go programs lagged badly behind humans, and even a few months of study could put a human ahead of the strongest engines of the time. The structural reason was simple: Go presents too many variations for brute-force search to solve. Practical play leans on a blend of local reading and feel. Positions are unpredictable enough that players often cannot calculate everything precisely and instead choose moves built on intuition. Only with new algorithms did machines begin to close the gap.

Handicap play lets the weaker side place stones before the first move, two or three or five or more, so matches stay meaningful across skill gaps. Those same setups became a stress test for early engines. Even positions that looked overwhelmingly favorable, when the entire board was filled with black stones, still ended with humans beating the programs quite effortlessly.

The Breakthrough

For years the curve was gradual, new algorithms, better programs, steady but unspectacular progress. Then came 2015, and the story bent sharply.

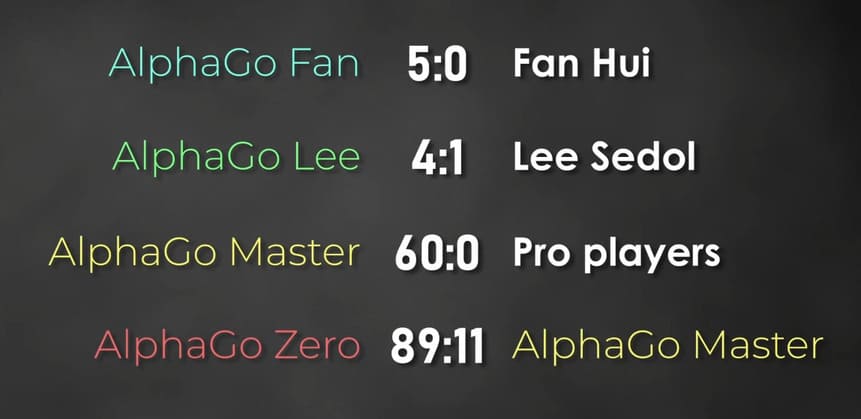

DeepMind’s team reached out to Fan Hui, a two-dan professional originally from China, then living in France, and, crucially, a three-time European champion. It was a natural first test. In October 2015 the two sides played a five-game match. Hui, like most professionals of the era, was skeptical; experience suggested no program could really beat a strong human. That expectation collapsed almost immediately. After the first game it was clear the balance had shifted, and the match ended in a clean sweep: five losses in five games. The result shocked many observers, yet the Go world as a whole did not feel decisively overturned; plenty of players suspected this still was not the “true” human-versus-machine reckoning.

A bigger trial was inevitable. The next year’s opponent would be a legend: Lee Sedol of South Korea. In 2015 terms, the comparison that stuck was “the Michael Jordan of Go,” eighteen international titles, famous for an aggressive, intuitive style. Before the match, Lee reviewed the five Fan Hui games and, like Hui before him, remained unconvinced; the level on display felt beneath his own, so he expected to win comfortably. What he did not see coming was AlphaGo’s additional training before their meeting, preparation that would tilt the stage for March 2016.

Lee Sedol vs. AlphaGo

Anticipation built through early 2016, until the question felt cultural as much as competitive: what happens when a living legend meets a machine that keeps getting stronger between outings? Wagers leaned toward the human, and most bets backed Lee Sedol. The event spilled beyond the playing room, with live commentary in multiple languages and giant outdoor screens in Seoul turning streets into viewing halls, so when the first move hit the board, it felt like a global stress test of human intuition.

Game 1: Early Fighting and an Unexpected Machine Style

Conventional wisdom said a program should avoid early chaos against a top pro. AlphaGo did the opposite, initiating a sharp fight right out of the opening, precisely the scenario thought to favor the human, and won with disarming ease. Lee was taken aback, and the real battle, it seemed, had only just begun.

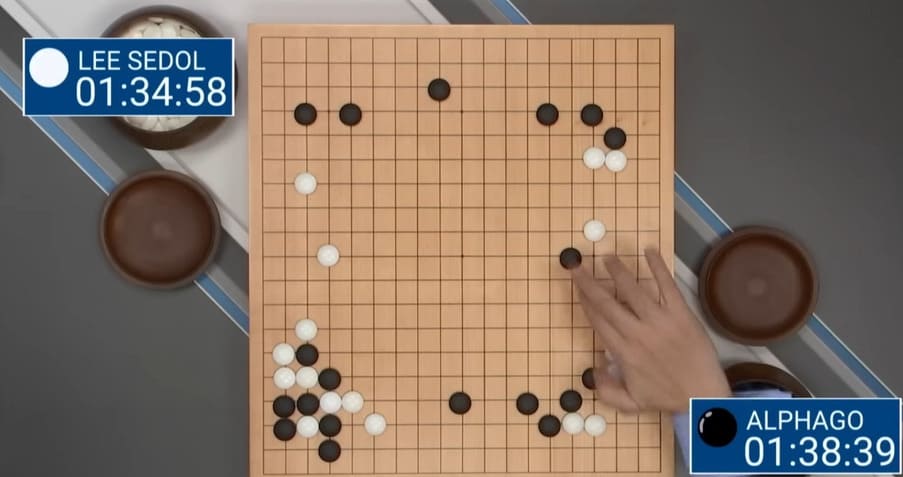

Game 2: The “Impossible” Move 37

The second game produced a moment that froze the room. On move 37, the machine chose a line humans “don’t play.” It cut straight across basic table manners, the kind of thing drilled as fundamentals, yet there it was on the board, calm and unapologetic. Viewers were stunned, and the move “surprised everyone watching.” By human doctrine, that choice “just cannot be played.” And still, the system played it, then made it work. In that instant, the match stopped being a referendum on database mimicry. It became a demonstration that the program could transcend its original datasets, step past the human games it learned from, and find something creative. The rest of the day confirmed the shock. AlphaGo won the game and moved ahead 2–0, forcing Lee Sedol into the territory where only extraordinary ideas would keep the match alive.

Game 3: Trying to Flip the Script

With the match tilting away, Lee aimed for the only path left: force complications and start a huge fight from the early opening. It did not bite. AlphaGo stabilized, won again, and at 3–0 the match was effectively over.

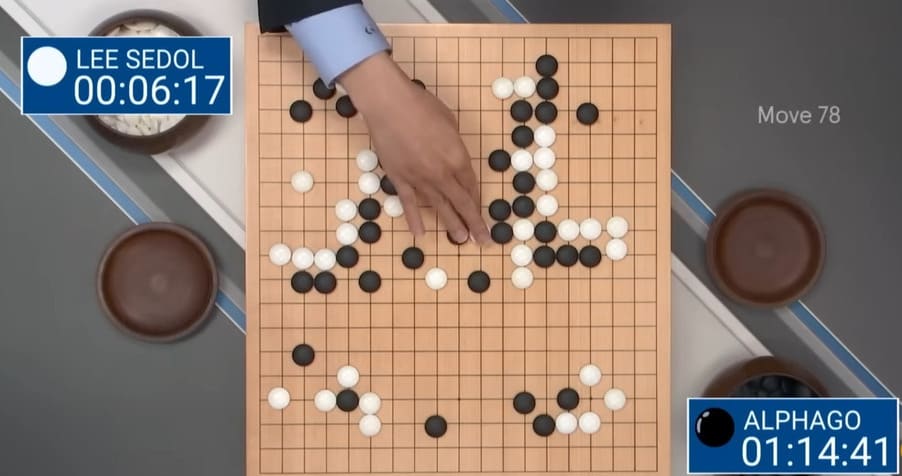

Game 4: The Human Masterpiece, Move 78

Midway through the fourth game, the match seemed settled. AlphaGo led by roughly ten points, a margin that usually signals a quiet glide to the finish at this level. Then, in a position that looked closed to miracles, Lee Sedol found a single, stunning idea that no one on site could see. The move hit the system’s blind spot. AlphaGo’s evaluation faltered, could not resolve the position, and the momentum flipped. That spark has a name in Go lore, Move 78. Later study, with much stronger AI than the 2016 version, suggested the tactic should not work in principle, yet against that build, on that day, it did. Lee converted the advantage and won. Beyond the scoreboard, the scene mattered because it proved something about the match’s spirit. The first three games had shown a machine capable of quiet strength and startling invention, and the fourth showed that human creativity could still force a crack in the armor. It remains the lone human win against that particular machine, an exception that became legend.

Game 5: Sealing the Match

The fifth game arrived with momentum freshly shifted and nerves taut on both sides. Lee pressed again, looking for complications and ways to reopen the board. AlphaGo met the pressure with calm, traded efficiently in the middlegame, and turned a small edge into a stable lead. When the territorial count became clear, Lee resigned. The audience saw both the human masterpiece of the day before and the system’s ability to absorb it and answer in the very next game.

Final Score, Lasting Meaning

The match ended 4–1. Beyond the scoreline was a new pattern: an AI that could learn fast between matchups, step outside human habits, and still deliver under the brightest lights. That was the week humans finally lost to machines at Go, and the week creative search by AI stopped being speculative and became visible on the board.

For a deeper look at the match’s legacy and what it means for players today, see our article “Lee Sedol and AlphaGo: The Legacy of a Historic Fight!”:

From AlphaGo to AlphaGo Zero

After Seoul, stronger builds kept arriving, but the real bend in the road came a year later, when a very different system stepped onto the stage with a new name and a new premise.

The new system was called AlphaGo Zero, “Zero” because it learned Go from scratch. No archive of human games, no inherited joseki or pro habits, just the basic rules and then relentless self-play.

Early on, the games were awful by human standards: thousands of stumbles, moves that looked almost random. But the learning loop did not care about elegance; it cared about outcomes. With millions upon millions of self-play games, the system’s strength climbed steadily.

The payoff was blunt: the from-scratch learner surpassed every earlier version trained on human data. In other words, removing the human starting point, excluding the “human factor,” turned out to be better for the machine.

Why it mattered was not just speed or strength but direction. A system unmoored from human examples could explore lines people had never taught it, answer long-standing questions with confident choices, and normalize ideas that once looked unorthodox. Years later, superhuman Go AI sits in everyone’s toolkit, a blessing and a curse for how players study and how the game evolves.

To set up modern Go analysis engines on your own machine, follow our step-by-step guide “Installing Software for Go Game Analysis with AI”

Beyond Human Go: A Beginning, Not an Ending

The story does not end on a bleak note. That victory nine years ago meant more than teaching a machine to play Go, or tic-tac-toe or StarCraft. It revealed a method: AlphaGo showed how to train AI correctly for complex tasks.

By 2025, that method reaches far beyond a 19×19 board: systems that understand human speech, generate images and video, compose music, and much more are everyday reality. Yet the research frontier remains open, unfinished work with an uncertain ceiling on what it might mean for our species.

Around Go itself, the conversation widens. Study is no longer only “how to play this game,” but also the ideas orbiting the board, the technology, the creativity, the implications for players and fans. The final line is not a period but an ellipsis: from one board to the wider world, the next move is still unwritten.

Оставить комментарий