Exploring the Role of Go in Blue Eye Samurai

The animated series Blue Eye Samurai captivates audiences with its rich historical setting and attention to detail, taking place in Japan’s Edo period. From how characters move to what they eat, the creators meticulously researched every aspect to make the world feel real. But amidst the stunning visuals and the engaging plot, one detail stands out to Go enthusiasts—the appearance of the ancient game of Go.

This article is a text version of the YouTube video from the Go Magic channel, where we dive into the cultural and narrative significance of Go in the series. You can explore more Go-related content on the Our YouTube channel, where we discuss strategy, history, and the beauty of the game.

In this article, we will explore why Go plays such an important role in Blue Eye Samurai and how it reflects the larger themes of the show.

Cinematic Inspirations in Blue Eye Samurai: A Nod to Film Legends

As you watch Blue Eye Samurai, there’s a good chance you’ll get a sense of déjà vu—like you’ve seen something similar before. And that’s no coincidence. The show is packed with cinematic references, and the creators have been very open about the films that influenced them. It’s clear they wanted to share their love for classic cinema with the audience, especially the masterpieces of Japanese filmmaking.

One of the biggest influences on the series is the work of Akira Kurosawa. If you’re familiar with his movies, you’ll instantly recognize the epic sword fights and intense, dramatic moments. But it doesn’t stop there. The creators also drew inspiration from directors like Kenji Mizoguchi, known for his elegant and thoughtful storytelling, as well as from the movie Double Suicide by Masahiro Shinoda, which brings a dark and haunting feel to the story.

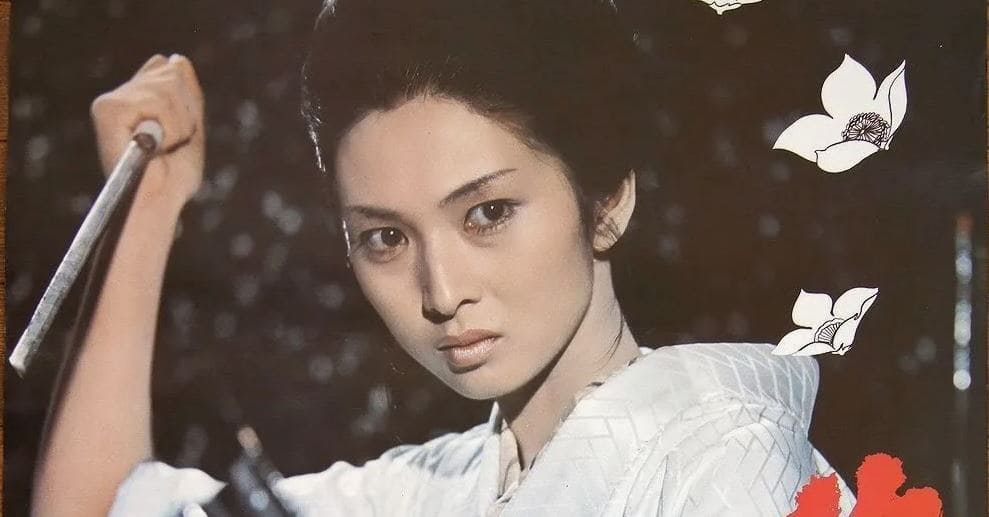

And it doesn’t end with just those films. Another standout influence is Lady Snowblood by Toshiya Fujita, a tale of revenge and resilience that mirrors the themes of Blue Eye Samurai perfectly. You can even spot nods to A Black Cat in a Bamboo Grove by Kaneto Shindo—a film that’s famous for its eerie atmosphere and suspense. The respect for these classic works is so strong that one of the characters in the show, Heiji Shindo, was actually named after the director Kaneto Shindo. It’s a subtle but meaningful tribute.

But it’s not just Japanese cinema that shaped Blue Eye Samurai. You can also feel the influence of Clint Eastwood’s westerns, with their lone warrior characters, and Quentin Tarantino’s stylish, sharp-edged storytelling. The interesting thing about Tarantino is that his work, like Kill Bill, was heavily inspired by classic Japanese movies, and now the circle has come full swing—his work has gone on to inspire others to tell stories set in Japan. History makes a full circle, and it’s a beautiful thing to witness in Blue Eye Samurai.

Symbolism in Character Names: More Than Just Words

In Blue Eye Samurai, the creators didn’t just put effort into the historical details—they also infused deeper meaning into the very names of the characters. Take the main character, for instance. Her name is Mizu (水), which means “water” in Japanese. This isn’t just a pretty word; it’s symbolic of the qualities she needs to survive and succeed in her mission. Water represents fluidity, adaptability, and the ability to flow around obstacles—all traits that Mizu embodies as she faces her challenges. Her journey is like water, constantly shifting and finding new paths.

Then there’s Ringo (林檎), her unlikely companion, friend, or perhaps even servant. In Japanese, Ringo means “apple.” At first, you might think, what does an apple have to do with anything? But the contrast between water and apple in their names is striking. These two couldn’t be more different in name and symbol, yet they travel together and learn from one another, forming a bond that helps them survive the dangers they face. It’s an interesting dynamic, showcasing how characters with seemingly opposing traits can grow and evolve through shared experiences.

Another significant character is the samurai Taigen (泰源), who plays a pivotal role in the story. His name is also carefully chosen. The character “Tai” (泰) can signify peace, harmony, or even tranquility, while “Gen” (源) refers to a source, origin, or foundation. Together, the name Taigen can be interpreted as a balance between inner peace and inner strength—qualities essential to a samurai. The name hints at Taigen’s internal conflict, as he struggles with his own sense of honor and vengeance. And if you’re wondering about his future, the significance of his name suggests that Taigen may play an even larger role in a possible second season. The creative team knows where the story is headed, but whether it gets greenlit is another question. We’ll just have to wait and see.

Then there’s Princess Akemi (明美), whose name is rooted in the traditional values of beauty and grace. It’s no coincidence that her name reflects these qualities, as many parents in Japan, and historically in China, choose characters associated with elegance for their daughters. Akemi (明美) means “bright” (明) and “beautiful” (美), perfectly fitting the image of a traditional, refined woman in a patriarchal society. Yet, as we’ll see, her story is much more complex than just being a symbol of beauty.

Life in the Edo Period: Strict Social Hierarchy and Cultural Challenges

As Blue Eye Samurai unfolds, the setting of Edo period Japan comes into sharper focus. This era, which lasted from 1603 to 1868, was a time of rigid social structure and stark divisions between different classes. The Japanese feudal system dictated nearly every aspect of life, and this is vividly reflected in the show.

The society was divided along strict, almost unbreakable lines. You were born into a certain social class, and there was virtually no upward mobility. If you were a peasant, you married into a peasant family. Samurai married samurai, and royalty married royalty. Theoretically, you could move down the social ladder, but moving up was out of the question. This is the harsh reality that many characters in Blue Eye Samurai face—there’s no escape from the status you were born into.

For women, the situation was even more constricting. As we see with Princess Akemi, women had little to no say in who they married or when. Marriages were arranged for political or financial gain, and personal feelings were often irrelevant. Women were generally seen as secondary in society, with few rights, and they had limited opportunities for upward movement unless through unconventional means, such as managing certain types of businesses. Even then, the nature of those businesses often carried a negative social stigma.

Despite the strict rules, there were exceptions. Life in Edo was not entirely black and white. The farther you traveled from the capital of Edo (modern-day Tokyo), the less rigid the feudal system became. In rural areas, some social norms were more relaxed, and the power dynamics shifted subtly. Still, for most women and men, the expectations placed on them by society were demanding and often unforgiving.

Take Ringo, for example. Like many characters in the show, he dreams of becoming something greater, but in the Edo period, you either were or you weren’t. You couldn’t just become a samurai, a person of influence, or even truly Japanese if you weren’t born into it. The social structure was rigid, and it’s clear that many characters are rebelling against this deeply ingrained system. Their struggles are personal, but they also reflect a larger dissatisfaction with the constraints imposed by their society.

One of the more interesting character arcs in this regard is Taigen. He is one of the rare figures who managed to climb the social ladder due to his incredible skill as a warrior. But, ironically, after achieving the status he sought, he starts to question whether it was the right path for him. In a way, Taigen’s journey symbolizes the deep conflict between personal ambition and the peace that can be found in accepting one’s place in the world. At the end of his arc, he yearns to return to a quiet, simple life in the countryside. Whether he can actually follow through with this plan is unclear, but his character serves as a reminder that climbing to the top isn’t always the answer.

For men in the Edo period, life was also a constant balancing act. A samurai could be both a bureaucrat and a warrior, expected to excel in battle yet also adhere to strict social codes. A wrong move, even something as small as using the wrong conjugation of a verb, could lead to severe consequences—even death. This immense pressure to be perfect is part of what drives the characters in Blue Eye Samurai, and we see it in the internal conflicts they face, particularly after Mizu defeats Taigen in battle.

Taigen, who started as a peasant and earned his place in society through skill and hard work, loses everything when Mizu defeats him. In that moment, he not only loses a fight but the respect of the society that he worked so hard to gain. For someone in his position, a loss like that means dishonor, and in the Edo period, dishonor was akin to social death. He pledges his life to a rematch, not because he wants revenge, but because without his honor, he is nothing. If he doesn’t fight for his honor, he might as well return to being a peasant, with no future and no status.

Life in Edo Japan: The Struggle Between Duty and Ambition

In Blue Eye Samurai, the setting of Edo-period Japan is not just a backdrop, but a powerful force shaping the lives and choices of the characters. This period, known for its strict social hierarchy and rigid traditions, forms the foundation of the societal struggles many of the characters face. The Japan of this era was divided by class lines that were almost impossible to cross, and this unyielding system is a central theme in the story.

The Edo period was an age of extremes, where your birth dictated your fate. If you were born a peasant, you married within your class, and the same applied to samurai and royalty. Upward mobility was nearly unheard of. You could move down the social ladder, but rising through the ranks was a different story entirely. For women, the limitations were even more severe. Princess Akemi exemplifies the challenges women faced—her marriage was arranged, with little regard for her personal feelings or desires, a situation common for women of her rank in this patriarchal society.

Despite this, there were glimmers of flexibility, especially as you moved further away from the capital of Edo (modern-day Tokyo). In more rural areas, the rigid class structures loosened somewhat, giving rise to slightly more fluid social dynamics. But for most, the expectations placed upon them by this society were clear and uncompromising: stay in your place.

A character like Ringo, for instance, dreams of becoming something more, of transcending his current status. But in the Edo period, the concept of “becoming” was almost unthinkable. You were either born into a position of influence or you weren’t. The idea of transforming yourself into a samurai, for example, was out of reach for the vast majority of people. This harsh reality creates an underlying tension in the show, as characters like Ringo struggle with their aspirations in a world that refuses to let them grow beyond their social station.

Taigen is another compelling example of the complexities of social mobility in the Edo period. He is one of the rare individuals who managed to climb the social ladder through his exceptional skills as a warrior. Yet, despite achieving the status and respect that he longed for, Taigen begins to question whether it was worth the sacrifices. After being defeated by Mizu, Taigen finds himself stripped not only of his honor but of the social status he fought so hard to achieve. For a samurai, losing a fight is more than a personal failure—it’s a public disgrace. Taigen understands that, in the eyes of society, he has fallen from grace.

The stakes for men like Taigen were incredibly high. The pressure to maintain honor and status could be crushing. Samurai were expected to be perfect in every way—not only in battle but in their conduct, language, and social interactions. Even something as trivial as a poorly conjugated verb could lead to severe punishment. After his loss to Mizu, Taigen knows that his only option to regain his place in society is to challenge her again. His pledge for a rematch is not just about vengeance; it’s about survival. Without his honor, he is nothing, and he would be forced to return to the life of a peasant—something unthinkable after reaching such heights.

For Mizu, the struggle is different. Born into a box defined by her gender and foreign blood, she refuses to accept the limits imposed on her. By rejecting her “feminine” role, Mizu breaks out of the traditional expectations placed upon her and strives to become a samurai, something unheard of for a woman. In doing so, she disrupts the very foundations of the society she lives in, challenging not only her own fate but the system itself. Her journey to revenge and self-realization runs parallel to Taigen’s own quest for honor, yet they are driven by different forces—Mizu seeks to break free of the confines of her identity, while Taigen fights to preserve his.

Both characters highlight the intense personal and societal struggles of Edo Japan. Whether it’s through class, gender, or honor, the era demanded total loyalty to its rules, and breaking those rules often came at a great cost.

The Game of Go: A Metaphor for Life and Strategy

As Blue Eye Samurai continues, the story delves deeper into not just personal and societal struggles, but also into the philosophy of games and strategy. And that’s where the ancient game of Go comes into play. Go isn’t just a casual addition to the show; it serves as a metaphor for the complexities of life, power, and control.

Princess Akemi’s story takes a pivotal turn when her teacher, Seki (関), introduces the Go board back into her life. When Akemi questions why they stopped playing years ago, Seki’s response is simple yet profound: “Because you learned.” This exchange sets the stage for a deeper lesson—the game of Go isn’t just about winning or losing, it’s about learning, evolving, and mastering the constraints life presents.

For those unfamiliar, Go is an ancient board game that originated in China more than 4,000 years ago. Two players take turns placing black and white stones on a grid, aiming to control more territory than their opponent. Despite the simplicity of the game’s rules, the complexity quickly becomes staggering due to the 361 possible intersections on the board, leading to an astronomical number of variations in strategy. The endless possibilities of Go make it the perfect metaphor for life itself—complex, unpredictable, yet governed by a set of simple principles.

If you’re curious about learning this ancient game, check out our video tutorial on how to play Go, which offers a clear and engaging introduction. Or, explore our interactive guide to Go for step-by-step instructions on how to play and gain a deeper appreciation for how this ancient game ties into the themes of the show.

Back in the show, Seki uses Go as a teaching tool for Akemi, showing her that life, like Go, is about mastering the board you’re given. The game becomes a metaphor for control—of one’s emotions, one’s fate, and even one’s future. The board is vast and complex, much like Akemi’s life in feudal Japan, but it’s limited. The challenge lies not in breaking out of the constraints, but in mastering them. Seki’s lesson is clear: You don’t need to escape the box you’re in; you need to master it.

This idea of mastering your circumstances, rather than running from them, resonates deeply with Akemi’s journey. She is trapped in a society where her choices are limited by her gender and status, but through Go, she begins to see that there are ways to navigate these limitations, ways to outthink her opponents—both on the board and in life.

And the name Seki (関) itself isn’t just a random choice. In Japanese, it can mean “gate,” symbolizing the idea of Seki as a gatekeeper to Akemi’s understanding of life. But interestingly, in the game of Go, Seki is a specific term used to describe a situation where neither player can progress without causing their own defeat. It represents a state of perfect balance—a stalemate where both sides coexist in harmony, unable to overpower one another. This balance, much like Akemi’s delicate position in society, requires wisdom and strategy to maintain.

By the end of the series, we see that Go is not just a game for Akemi—it’s a path to self-realization. Her teacher, Seki, gives her a final lesson that transcends the board. Life may be a complex and unpredictable game, but with patience and strategic thinking, it can be mastered.

If Blue Eye Samurai has sparked your interest in Go, or if you’re eager to explore the game further, you’re in the right place! Our platform offers a wealth of interactive courses and practical exercises designed to help you master Go at your own pace.

This article is our first text-based version adapted from a video! Did you like it? Want more articles like this? Let us know in the comments. We’d love to hear your thoughts and suggestions!

Great article! I hadn’t noticed the play on names in the series before, but it just goes to show once again that this is an outstanding show that deserves more attention. I’m looking forward to season 2.