From Coffeehouse Stones to the World Stage: The Unlikely Rise of Kyrgyzstan’s Go Dynasty

The Coffee Shop Revolution

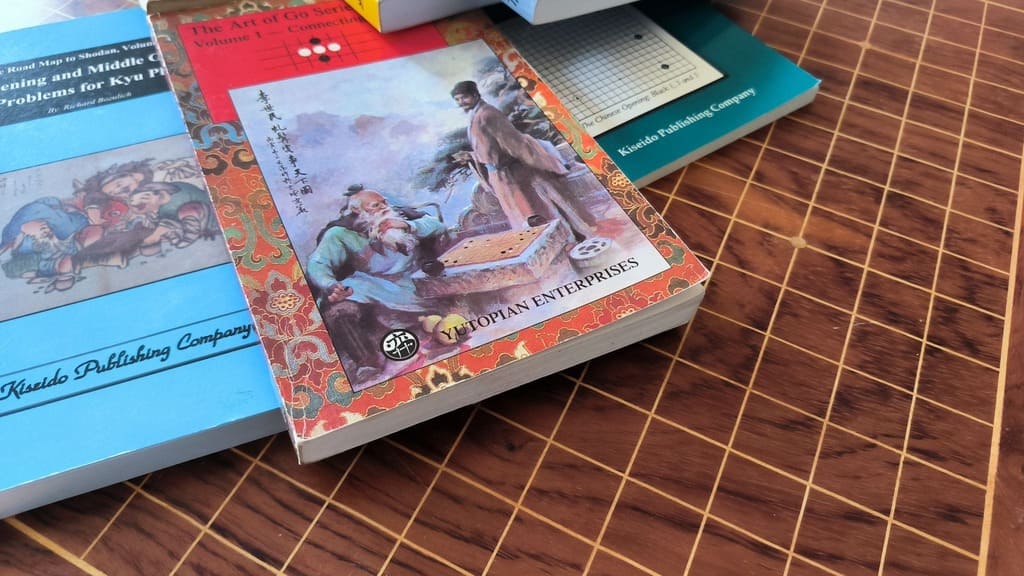

The first Go board in Kyrgyzstan was born not from polished wood, but from shared curiosity—a coffee shop napkin transformed by hand-drawn grids, where friends gathered to decode the mysteries of a game they’d only just discovered.

“We looked like conspirators,” Davron laughs. “People thought we were plotting a crypto scheme. When we explained it was a 2,500-year-old strategy game, they’d say, ‘So… Asian chess?’”

But the obsession stuck. By 2022, their coffee shop collective had morphed into something improbable: the Kyrgyz Go Federation.

The Improvised Rise of Kyrgyz Go

The turning point came when they moved into ololo Coworking, a hive of freelancers and startups. A single Go board tucked into a corner became a magnet for programmers decompressing after coding marathons. Teachers and accountants soon followed, paying small fees that transformed Go from a hobby into a cultural experiment. “That first paid membership?” Davron smiles. “It was a silent revolution.”

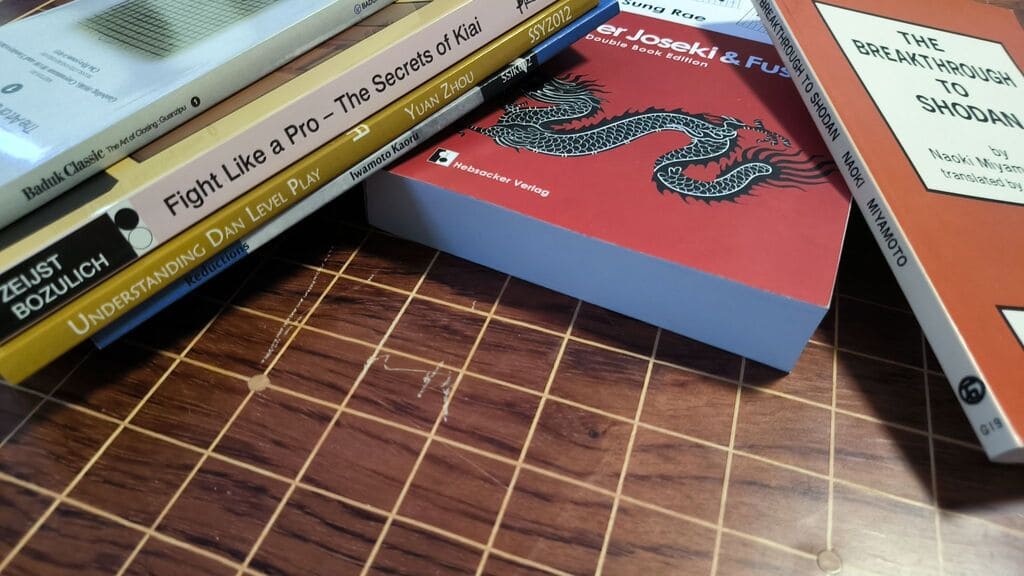

By 2022, the revolution went viral. Instagram challenges dared newcomers to “Beat us, win coffee,” while CEOs sparred in corporate tournaments framed as “negotiation drills.” Influencers, lured by the game’s cerebral appeal, sparked a wildfire: Go tutorials amassed 7 million views, many soundtracked by the twang of komuz lutes. “Suddenly,” says educator Aigerim, “kids called it ‘anime chess’ and begged to play during math class.”

The game soon escaped cities entirely. Workshops reached herders in Naryn, farmers in Talas—communities where stones once counted sheep now plotted territory. 7,000 people learned the basics; 500 became regular players. By 2024, what began as café scribbles had birthed 10 clubs, 80 tournaments, and a federation punching far above its weight: historic debuts at the World Go Championship, membership in the International Go Federation, and a recent ISGS Award for grassroots impact.

“This is an incredible story that’s only five years old,” says Davron Yuldashev, President of the Kyrgyz Go Federation. “Five years ago, I discovered the game completely by chance—I’d only heard about it from a friend who didn’t even really know the rules. I had to learn by intuition, playing against a bot in a mobile app. The game hooked me so deeply that I played nonstop for 12 hours, from evening until morning. And by dawn, after losing dozens of games, I had gained enough experience to start winning and even reached the 20-kyu level.

That meager experience and superficial knowledge were enough for me to start teaching the rules to my friends and acquaintances—after all, I wanted to play against real people. And now, five years later, I can see how our small group of enthusiasts has managed to achieve so much.”

“Last year alone, we hosted 90 events—festivals, masterclasses, even a tournament on paddleboards,” Davron says. “But our proudest number? 2,000+ faces at those events. Proof that Go isn’t just a game here. It’s a whole new culture.“

Stones, Waves, and the Art of Letting Go

The third Issyk-Kul Go Cup (June 20–23, 2024) drew over 130 players to the “Pearl of Central Asia,” including European top-tier competitors and a special guest: Korean professional Seongi Kim 5p. Though not competing, Kim immersed himself in the festival spirit—analyzing games, leading workshops, and discussing strategy with players of all levels. His presence bridged the gap between pro expertise and grassroots enthusiasm.

Mornings focused on tense matches; afternoons erupted into hybrid chaos. Korean pros analyzed kifu under pine trees, then learned toguz korgool from elders. Russian programmers debated AI joseki while paddleboarding on the lake. Evenings brought komuz lute melodies and blitz games under fairy lights, where laughter drowned out the scorecards.

The tournament also saw standout performances from established names. Jonas Welticke 6d, Germany’s reigning champion, claimed second place with games described by observers as “technical poetry,” blending sharp calculation with unorthodox aggression. British participant Quintin Connell later reflected on the event’s unique atmosphere: *“Where else could you watch a 6-dan’s masterpiece by day, then lose to a teenager in beach volleyball by night?”*

This fusion of high-level play and lakeside camaraderie—SUP surfing, bonfire blitz matches, and basketball tournaments—solidified Issyk-Kul’s reputation as a tournament where prestige and playfulness share the spotlight.

“We’re nomads at heart,” says Davron. “Go isn’t about conquering the board. It’s about leaving room for the unexpected.”

“When I organized our first major tournament in 2022,” Davron recalls, “the pressure was overwhelming – I lived with constant stress every single day.” The resort owners demanded substantial deposits and guarantees to reserve such a large number of rooms. Moreover, the venues would only offer group discounts if we booked at least 100 beds. “I poured tremendous effort into attracting enough participants, and fortunately, we succeeded in gathering 120 players that year – including competitors from across the CIS countries.”

“We were attempting something completely new to us, requiring complex logistics coordination and meticulous scheduling. The toughest part was running multiple parallel events alongside the main tournament matches.“

“But the greatest stress of all was the children,” Davron admits with visible relief. “I prayed every single day that nothing would happen to them—we simply didn’t have the resources to watch them all closely, especially since not every child came with their parents.” He shakes his head at the memory. “In hindsight, we were incredibly lucky: the kids turned out to be calm, bright, and completely absorbed in Go. They played during the tournament, then kept playing through the evenings—sometimes even late into the night. The game was all they cared about.”

“And now we’re preparing for our 4th Issyk-Kul Cup,” Davron says with evident pride. “We’ve gained substantial experience in organizing these events—some even say our tournament resembles international Go congresses, but with a unique nomadic flavor and Kyrgyz cultural elements, all set against the breathtaking backdrop of our mountain lake.”

Issyk-Kul Go Cup 2025: Where Strategy Meets Nomadic Soul

At the edge of the world’s second-largest alpine lake, where snow-capped peaks pierce cobalt skies, a different kind of battle unfolds. Not with swords or horses, but with black and white stones. The Issyk-Kul Go Cup has always been more than a tournament—it’s a pilgrimage for those who believe strategy thrives where logic meets wilderness. In 2025, it becomes a manifesto.

Given what we know from previous years, it’s easy to picture what a typical day of this tournament might look like.

Dawn: The Stones Rise

The day begins as all great Go games should: with silence, clarity, and the faint tang of pine needles in the air. At OlaBar beach shack, 200 players from 20 countries bend over boards, the McMahon system pairing a Tokyo tech CEO with a Kazakh herder’s daughter. A Ukrainian artist sketches the scene—“Go as meditation,” she labels it.

The prize pool ($1,000+) lures some, but the whispers tell another story. “Win here,” says a Kyrgyz player, “and you’ve beaten the lake, the mountains, and your own distractions.”

Noon: Lessons from the Land

Between rounds, the festival tempts. Not with gimmicks, but with cultural gambits designed to sharpen minds:

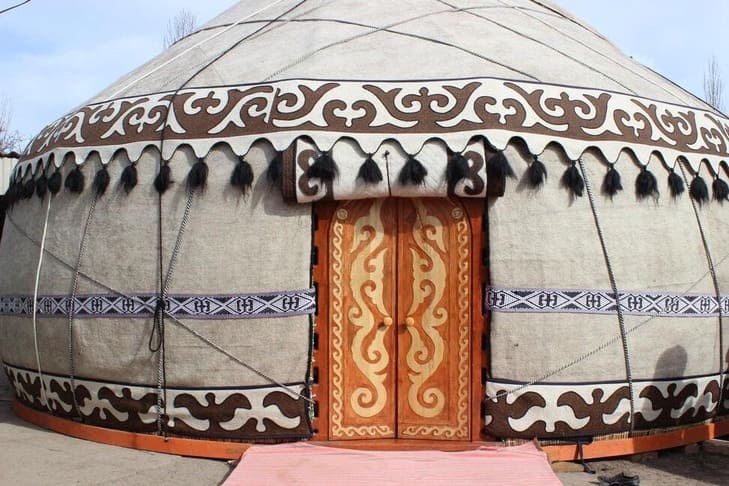

- Yurt Logic: Assemble a nomadic dwelling with artisans. “Every loose rope is a weak fuseki,” warns a craftsman. “Tighten your knots, tighten your zones.”

- Toguz Korgool Cross-Training: Masters of this ancient stone game challenge players to rethink resource management. “You hoard territory like sheep,” teases an elder. “But can you survive a drought?”

- Archery Zen: Draw a traditional bow, aim at felt targets. “Focus here,” says a coach, “and your endgame reads will sharpen.”

Sunset: The Hybrid Games Begin

As shadows stretch, OlaBar morphs into a crossroad of cultures:

- At the Silk Road Games Hub, a Seoul entrepreneur learns xiangqi from a Bishkek student, while Kyrgyz teens master shogi’s dizzying promotions.

- Over fermented mare’s milk tea, a debate erupts: “Is a keima like a horse’s jump?” A German philosopher argues yes; a local herder counters, “No—it’s a wolf circling prey.”

- Blindfold Blitz begins at dusk. No clocks, no komi—just intuition and the hum of the komuz lute.

Moonrise: Where Legends Are Forged

Nightfall strips Go of its formality. Under fairy lights, a Nomad Handicap tournament begins:

- Top players surrender stones and answer trivia about Kyrgyz epic poetry.

- A “Best Blunder” award is decided by crowd applause. The winner? A Dutch architect whose overplay sparked a 50-move ko battle. “I’ll frame this trophy,” she grins. “It’s the most fun I’ve ever had losing.”

By midnight, the shore thrums with stories. A Tokyo salaryman teaches atari to a shepherd. A Turkish designer learns alchiki (sheep knucklebones) from kids.

What began as ink-stained napkins in a Bishkek café has become Central Asia’s quiet gaming revolution. The Issyk-Kul Go Cup, now a global magnet for players, is merely the tip of the iceberg. Across Kyrgyzstan, Go thrives in schoolyards where kids debate ladders over lunch breaks, in corporate offices where CEOs reframe mergers as sente moves, and in mountain yurts where herders see ancestral wisdom in every stone placed.

This isn’t just a tournament’s legacy—it’s a testament to a nation that turned a 2,500-year-old game into a cultural language. From 10 players in 2020 to 500 today, Kyrgyzstan’s Go community whispers a truth louder than any championship trophy: Great things grow where curiosity meets stubborn joy. The stones keep spreading. The world is starting to notice.

The Bones of the Event

- When: June 19–23, 2025

- Where: Lake Issyk-Kul, Kyrgyzstan

- Register: https://sengoku.net.kg/kgf/

- Bring: An open mind, a love for chaos, and your worst blunder (it’ll become legend).

No guarantees about the weather, the lake, or your pride. Guaranteed? Stories you’ll recount for years.

Leave a comment