Go and Buddhism

If you take a look at the usernames on OGS, you will see that they roughly fall into two categories: names where you can immediately see who it concerns, and names where there seems to be no direct link between the username and the player’s real name. For example, my online Go name is not ‘Slooven1966’ or ‘Go-gerard-go’, but ‘Tsultruim’, a Tibetan word that literally translates as ‘moral self-discipline’.

Where does that come from? Well, Tsultruim (or Ngawang Tsultruim in full, but that sounds so formal) is my Buddhist name, which I got in 2009 from my teacher, the Tibetan geshe Ngawang Zopa. It is customary, when you are an apprentice, that your teacher gives you a name that he thinks suits you. It can be something that describes your character, or something you can still work on. It is up to the student to find out which one of these is most appropriate for them.

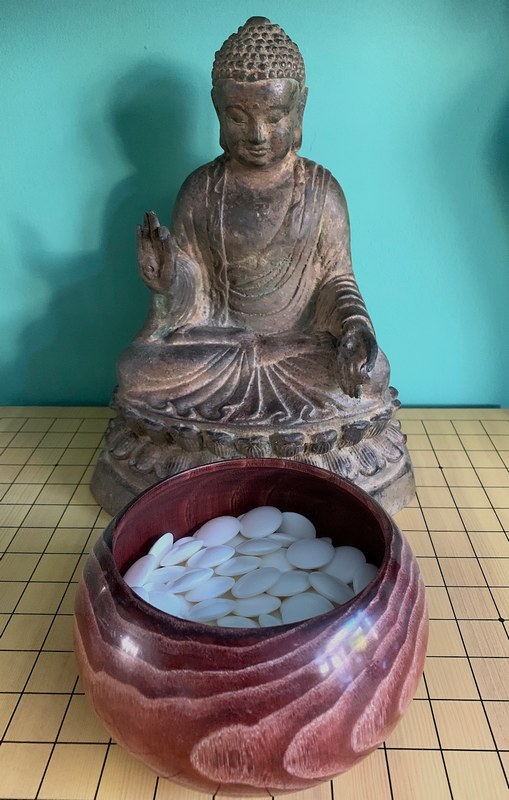

It kind of depends on who asks, but if I get asked the question ‘what does Go mean to you?’, I prefer to answer “Go is a great fun game, and for me also a Buddhist practice”. I’ve been trying to give Buddhism an active role in my life for years, but that’s something I don’t usually talk about very much. However, it means a lot to me, and I see it reflected in my daily life in many ways. This is also the case in Go, and I think it would be interesting to go a little deeper into this.

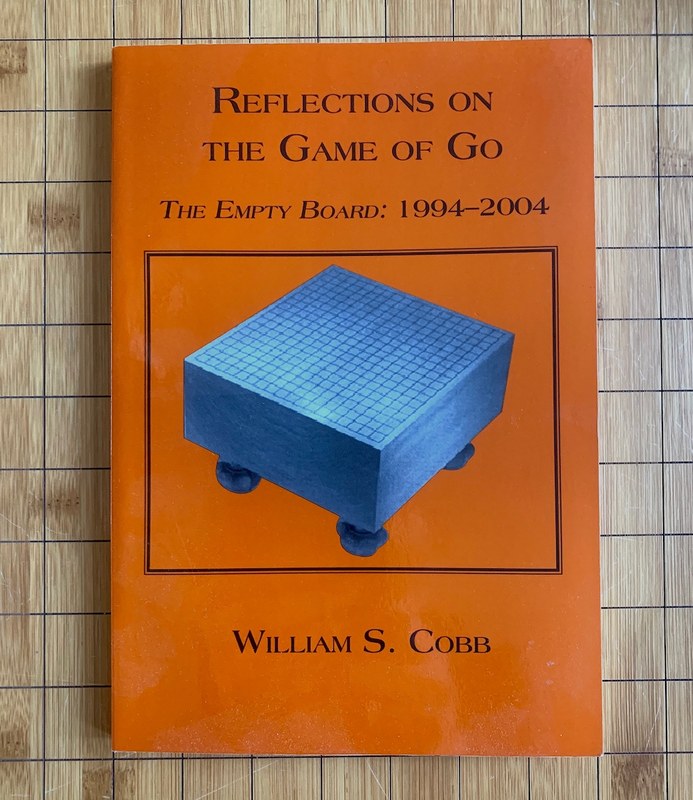

I will talk about some key concepts from Buddhist teachings, and the way in which I see those concepts in the game of Go. I was inspired by the great book ‘Reflections on the Game of Go’, written by Go player and Buddhism practitioner William Cobb. Well worth a read!

We’ll take a look at the following four concepts:

- Meditation

- Transience

- Emptiness

- Karma

Meditation

The core practice of Buddhism is meditation. And contrary to popular belief, that does not mean ‘thinking about nothing’ or ‘achieving ultimate inner peace’. Meditating means nothing more than staying fully in the here and now, no matter what presents itself. Since that is very difficult, we make it a little easier on ourselves by creating calm, manageable conditions in which to practice this. During formal practice this means: sitting in an active upright position, typically on a pillow, not distracted by anything, and then just concentrate on your breathing.

But you can do this practice anytime and anywhere. Also behind the Go board. And just think what that could mean for your game, if you were not constantly distracted by thoughts and feelings that don’t matter at all. And I’m not just talking about ‘what are we going to eat tomorrow?’ or ‘did I put the garbage outside?’, but also thoughts about the game itself.

If you only put energy into finding the best move you can make at that moment, it opens up a liberating way of playing. Thoughts such as ‘I have to win this game, because only then will I have a chance to win a prize’ or ‘Oh dear, a lot of people are watching, what on earth will they think if I play this move?’ are disastrous for the quality of your game.

It all sounds so easy: be in the present moment with your full attention. Just do it now… and now… oh yeah, and even now.

But just wait and see what happens if you try it…. well, that’s why it’s called a practice; you’re ‘allowed’ to let it go wrong quite often! Even now. And now.

Transience

Buddhism states that nothing lasts forever without changing. ‘Everything that has a beginning also has an end – make peace with that and all will be fine’ is a common saying attributed to the historical Buddha.

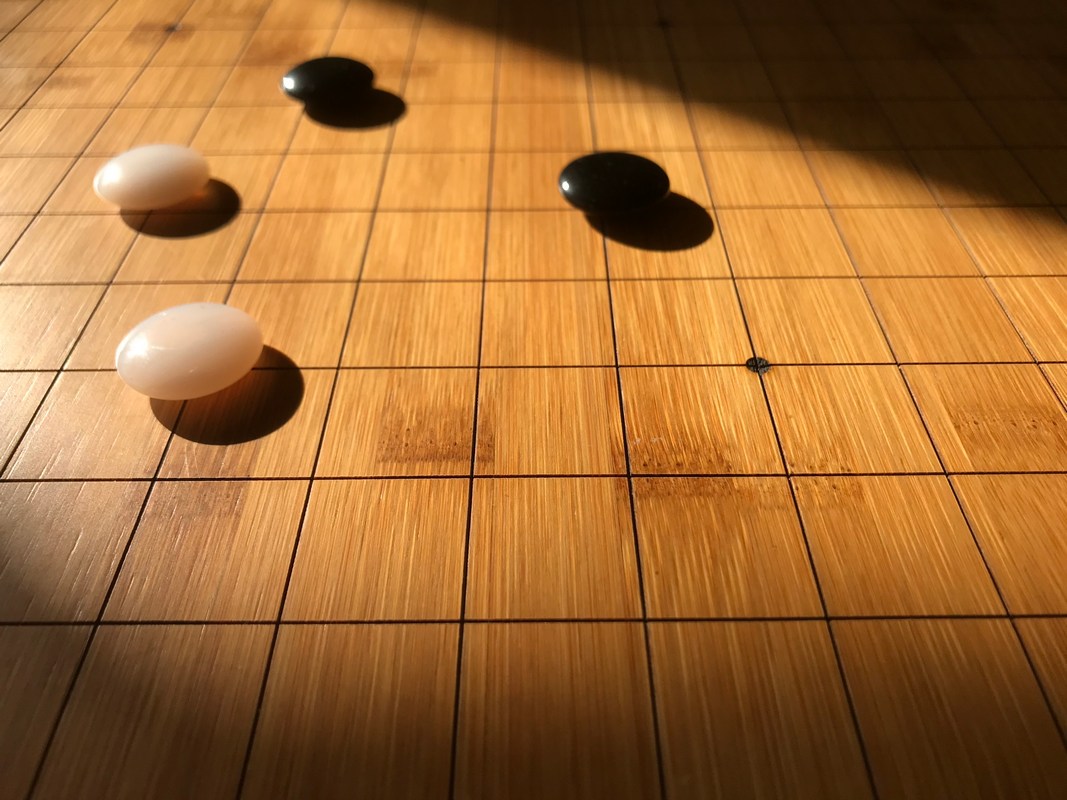

On the Go board you can see that in almost every move that is added to the game. Stones, which you wanted to build something with earlier, might no longer be important enough to defend later in the game. So you’d better give them up! If you insist on seeing those stones as equally important throughout the game, giving them up will prove to be very difficult: you want to keep everything going at once, which makes it seem like you’re juggling water, and then… everything collapses.

The slogan of the Youtube Go teacher Baduk Doctor is there for a reason: ‘The value of stones is always changing’. With every move you have to look at the position of that moment (there it is again – the here and now) and accept that it could be a lot different than before. Stones can become more important or less important. If you – maybe even against your better judgement – continue to cling to something that you put a lot of energy into before, it will really get in the way of your game. So accept that the game is subject to constant change, and always think from the perspective of the newly created situation. Also try to keep in mind that all this is not a ‘black and white thing’ – stones you give up are still on the board until your opponent actually captures them, and their presence can be of value again later in the game (that’s the infamous aji).

Sometimes it helps to step away from the board (or at this moment the computer screen) and, after a short break, literally look at the game with a fresh mind. Hopefully now less bothered by what had happened before. Especially if something big and unexpected has just happened (you lose a group that you had come to love so much) that is a good thing to do. This prevents impulsive reactions and opens the door to new possibilities in the game.

Emptiness

My favourite Buddhist concept. It is sometimes referred to as ‘without any self’. This means that nothing exists that stands alone or has its own definable identity. You can see this, for example, in a loaf of bread. That bread only exists because grain has grown (which in turn needs sunlight and water), a farmer harvested it, a baker got to work, the bread was transported to the store where you can buy it. etc. etc. If you think about this, the chain of interdependencies turns out to be unlimited.

But emptiness goes further: concepts are also empty. Look at a teacup. That is only a teacup (and no flower pot, for example) because we have agreed upon that. The function of teacup is given to the ceramic object by the user. And if you take this even further, this ultimately also applies to us. We only exist in a subjective relation with everything around us, and because that is constantly changing, so are we.

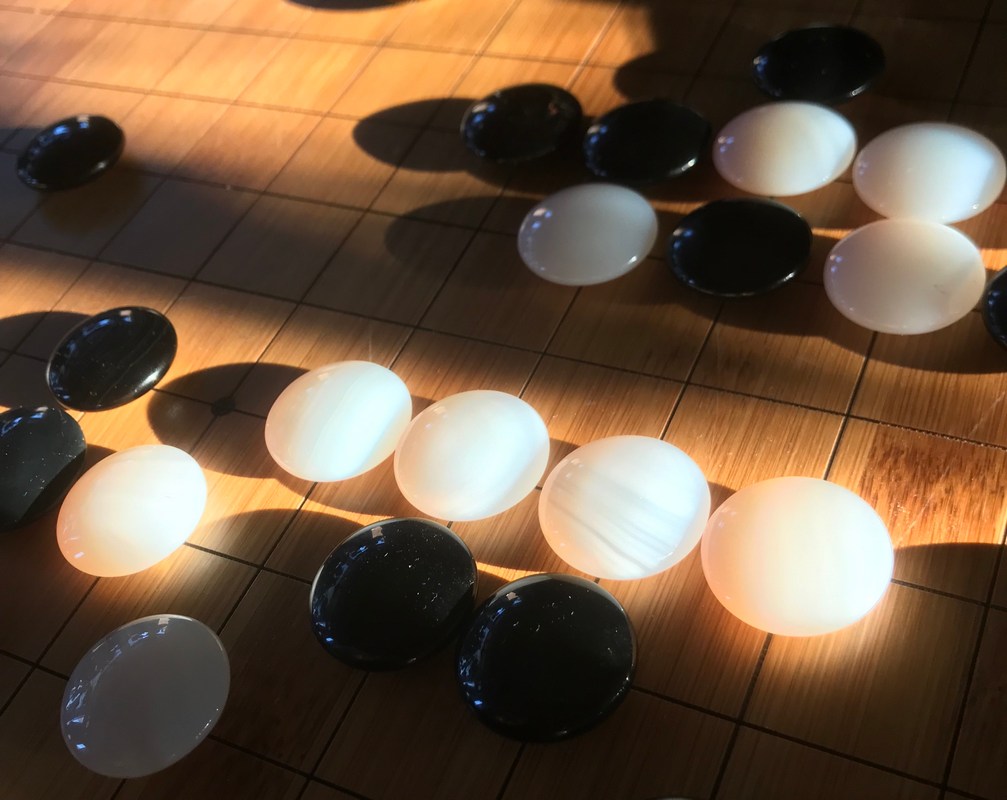

But what about the Go board? Look at a stone that is in a bowl and has not yet been played. How much is that stone worth? Is there a difference in value between these stones? You could say that each stone is worth the same amount, and attribute the value of 1 point to it. But in principle, this value only arises when the stone has been played and captured, because then it is 1 definite point for your opponent. And the points on the board are not even created by the stones themselves, but by the empty space (yes!) that the stones surround.

More so: the function and value of a stone is almost always something that arises in relation to the other stones and the position on the board. Many move names (hane, nobi, keima, kosumi) are positions of a stone played relative to stones that are already there. In the opening we play the first stones somewhere around the handicap point in the corner, and then that position determines the role of the stone.

I think that’s a wonderful idea: a game in which there is no inherent difference between the playing pieces, but where each stone can still take on such an individual role in the grand scheme of the game. When a stone is captured, its value reverts to 1 point, but the emptiness it leaves can again take on a completely different value. Which is just so beautiful!

Karma

There are few concepts of Buddhism that are as much discussed and misunderstood as karma. In non-Buddhist circles, it is often translated as ‘destiny’ (or even worse, ‘fate’) and its operation is described as a force that likes to deal red cards (or, if you’re lucky, a bonus). This is reflected, for example, in the (especially popular in America) saying ‘Karma is a bitch’.

In reality, the word ‘karma’ comes from Sanskrit and means little more than ‘action’. And the karma teaching describes that every action has a consequence. We all live in a world where actions are performed at every moment: consciously or unconsciously, purposefully or arbitrarily, by ourselves or by others. The consequences of these actions determine the reality around and inside us. Which of course changes at any time.

This is no different on the Go board: the position is created by the moves that you and your opponent played. Chance or statistics play no role: no dice is thrown, and every move is a conscious action (is ‘conscious’ the same as ‘sensible’? Well, I certainly won’t open that can of worms, but you’ll probably guess the answer).

If you see karma as an imposing force from which there is no escape, you will have a hard time on the Go board. Because this would mean that, if a position arises in which you find yourself in heavy weather, there is simply no escaping it. But karma not only says something about how situations can arise: it also states that every situation can change into another one. Again: through action. Your actions! Free to choose as you please.

Back to the Go position: the current position, whether it seems to be good or bad (if you can even call it that) was created by actions in the past, and indeed, those past actions cannot be reversed. That’s also the ruthlessness of the game, or, as Sai says so beautifully in the anime series Hikaru no Go: ‘That’s the weight of a move, once it’s played, it can’t be taken back’. But from the position that has arisen, the way is still open to many possible outcomes. And you can influence those with the actions you take from that moment on.

Of course, positions can arise that make it impossible for one of the players to win the game, but in those situations, it helps to think in a bigger perspective: all the consequences of your own actions (of course in combination with those of your opponent) have been converted into experience, and can lead to many more good actions in future games.

Go shows us a combination of all of the above at any point in the game. Nothing is permanent, the value of stones (and the emptiness between the stones) changes constantly due to their mutual connection, the past cannot be changed, but at any moment you have the opportunity to take new actions out of free decisions. If you can keep a calm mind in the midst of all this uncertainty, the best moves will appear on the board.

But wait… can I put this into practice myself?

Haha, hardly! But it’s an adventure to try again and again and especially to see the humour in all those ways in which you didn’t succeed…

Nice.

As a go player with a casual interest in Buddhism as a philosophy, this was a great read. Go is an incredible game that I’ll never truly understand.

Great article! 🙏🏻

I made similar conclusions when studying go, I am glad there are players, who come to the same subtle ideas 👍

Great article. I’d add that while the author primarily addressed lessons inherent in the nature of the game, there are numerous lessons to learn from each individual game as well. How many times I’ve suffered from not doing the things I should in favor of the things I wanted to do! Or paid a price for either avoiding necessary conflict or being excessively pugilistic. (That middle path is so hard to find!) After every game, win or lose, I ask what lessons I can learn. Yes, about becoming a better Go player, but even more about becoming a more enlightened human. The good news is that I’m not going to run out of room for improvement, in either domain, any time soon!

It was interesting! Thank you!

Good article thanks 🙂 It inspired me to look for a copy of Reflections on the Game of Go using bookfinder.com, but I got no hits.

Happily, I discovered the same author has published a newer, updated edition with the new title: Buddhist Philosophy and the Game of Go.

It’s on Amazon kindle, and also at https://gobooks.com/index.html

There are no diagrams in the book, so the problem of needing an iPad/iPhone/Mac to get SmartGO books diagrams to look really good (versus EPUB in Calibre not as good), well, no diagrams no problem.

I get no money/perks/swag from anyone to post this, just trying to help out, folks

I’m only just learning the game at 51, but this reminds me of things my maths teacher, who I played chess with, said about the game. An atheist teaching at a Catholic school, he definitely came across as the most spiritual mentor I had at the time! Go seems to be a completely different mystery from chess though. Because the pieces don’t move, I suppose, the notion of the piece deriving its role and ‘weight’ from the empty spaces seems quite mystical. I’m totally at sea, but loving it!

Such an enjoying article. Thanks

Very nice article

Great article. Thank you! 🙂