The Brief History of Go: A Chronicle from Ancient Times to Worldwide Acclaim

In the realm of intellectual games, few can boast the storied past and cultural significance of Go, known as Baduk in Korea and Weiqi in China. Often played by Japanese rules, Go’s journey from its Chinese origins to its modern status illustrates a fascinating interplay of culture, strategy, and history.

The Dawn of Go: A Chinese Invention Enhanced

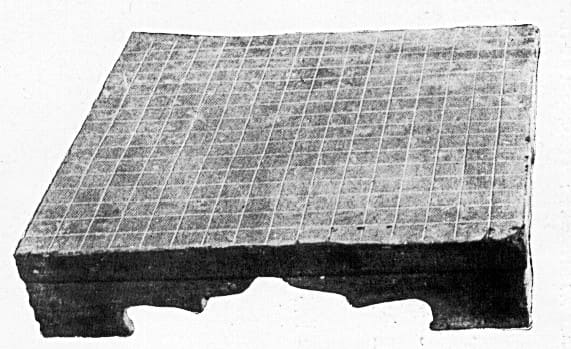

With its origins tracing back from 4,000 to 5,000 years in ancient China, Go stands as one of the oldest and most intellectually challenging games in history. Initially, it bore little resemblance to today’s game, with evolving board designs, square wooden stones, and varied starting positions. Archaeological evidence includes a 17×17 stone board from Wangdu County, dating prior to 200 AD, now in the Beijing Historical Museum. This artifact, alongside a silk picture of a Tang lady playing Go on a similar 17×17 board from around 750 AD, underscores Go’s longstanding presence in Chinese culture.

These findings, coupled with extensive background evidence in anecdotes, fairy tales, biographies, and mathematical manuals, affirm Go’s establishment in China, Japan, and Korea well before 1000 AD. The term “weiqi,” meaning “surrounding game,” was used historically, while “yi” appears in older texts. Interestingly, Go boards were smaller in ancient times, with 17×17 and even smaller grids – a tradition still observed in Tibetan Go today.

The Path of Go (Baduk) to Korea: A Tale of Strategy and Intrigue

Go likely came to Korea from China, possibly during Confucius’ time with Qizi’s migration, or around 109 BC during Chinese colonization. Qizi’s migration refers to the legendary journey of Qizi, a Chinese sage, who is believed to have traveled to Korea during the Zhou Dynasty, introducing various aspects of Chinese culture, including possibly the game of Go. Despite lacking concrete evidence of Go being part of these cultural exchanges, its significant impact is inferred from historical references.

The game’s presence in Korean culture is also evidenced by a 737 AD poem from Silla and an 880 AD stone Go board at Hae-in Temple, played on by scholar Ch’oe Ch’i-weon (but the Go sets still in the Imperial Repository in Nara, Japan, are believed to be of Korean origin and are much earlier). This history highlights Go’s integral role in Korean culture.

SunChang Go: Korea’s Unique Twist on Traditional Go

Traditional Go in Korea, dating from the late 16th century and possibly rooted in the game’s original form, differed significantly from Chinese and Japanese versions. The game, known as SunChang Baduk, ceased to be played around 1937.

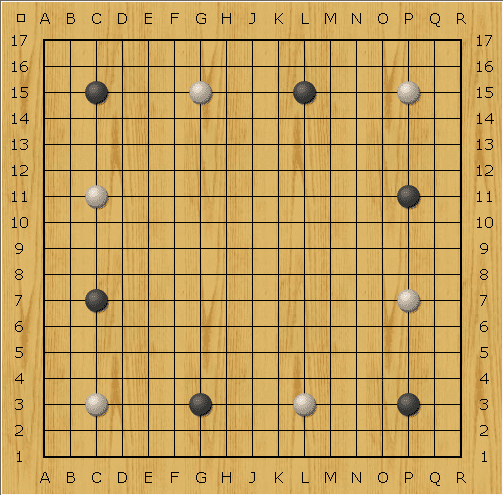

SunChang, a term central to the old Korean version of Go, known as sun-chang pa-tuk, carries multiple interpretations due to its varied character representations. The most common interpretation, ‘touring officers’, might either refer to a military context, suggesting guards who moved from post to post, akin to positioning pieces strategically around the Go board, or it could relate to the ritual placement of 17 ‘star’ points, traditionally called ‘guard points’ (as opposed to the more common ‘flower points’). In this interpretation, sun-chang symbolizes the initial phase of the game, where players circulate around the board, positioning their stones on these key points.

Alternatively, a less common but intriguing interpretation of sun-chang is ‘following one’s seniors’, suggesting a connection to the hierarchical administrative systems of the time, which were based on rank and order. This could imply a strategic approach to the game, mirroring the societal structure and the importance of strategic positioning and rank in both the game and in Korean society. In gameplay, players would place eight stones each on these designated points, with Black adding a ninth stone at the center to commence the game. Unlike in Tibetan Go, these initial stones in SunChang Baduk did not have a special status but were integral to setting up the strategic framework of the match.

Counting in SunChang Baduk was unique; it continued until all dame (neutral points) were filled, prisoners were disregarded, and the final score was determined by the territories enclosed by the minimum outside wall. Local variations existed, sometimes resulting in ties or altered victory conditions. Handicap play allowed Black to occupy points on the seventh line, excluding the center, while White took the center point. Example of counting in Sunjang Baduk

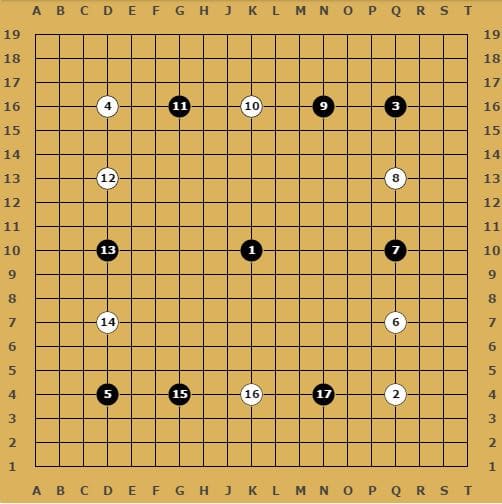

The ‘last game’, played between No Sa-ch’o and Ch’ae Keuk-mun and published in Chosun Ilbo in March 1937, exemplifies this traditional style. Black, giving a 4.5 point komi, ended with 57 points to White’s 53. Sun-chang go, historically a gambling game in Korea, tested players’ nerve and skill, particularly in life and death scenarios.

Adding to the legacy of sun-chang go, between 2013 and 2015, a resurgence of interest in this traditional form was seen when a group of enthusiasts on the Online Go Server (OGS) organized tournaments specifically dedicated to SunChang Baduk. These tournaments not only honored the historic nuances of the game but also introduced its unique strategies and styles to a new generation of players.

Go’s Journey in Japan: From Aristocratic Pastime to Shogunate Era

Go’s introduction to Japan is commonly attributed to Kibi no Makibi, who studied in Tang China in the early 8th century. However, its presence might date back slightly earlier, as indicated by the Taihō Code of 701 CE, which mentions the game. This timeline is supported by the Middle Chinese term 圍棋 *ɦʉi ɡɨ, adopted into Old Japanese as *wigə/wigo2 (represented by the man’yōgana 井碁). This term evolved into the contemporary Japanese reading 囲碁 (igo), a combination of kan-on and go-on phonetic elements.

Discover the rich history and cultural significance of Go, an ancient game of strategy, by watching our enlightening video:

In the Nara (710–794 CE) and Heian (794–1185 CE) periods, Go flourished as an aristocratic pastime, often featured in literary works like “The Pillow Book” and “The Tale of Genji.” The Muromachi period (1336–1573) saw the emergence of semi-professional Go players, serving powerful clans.

The Renaissance of Go in Japan: The Heyday of Great Strategists

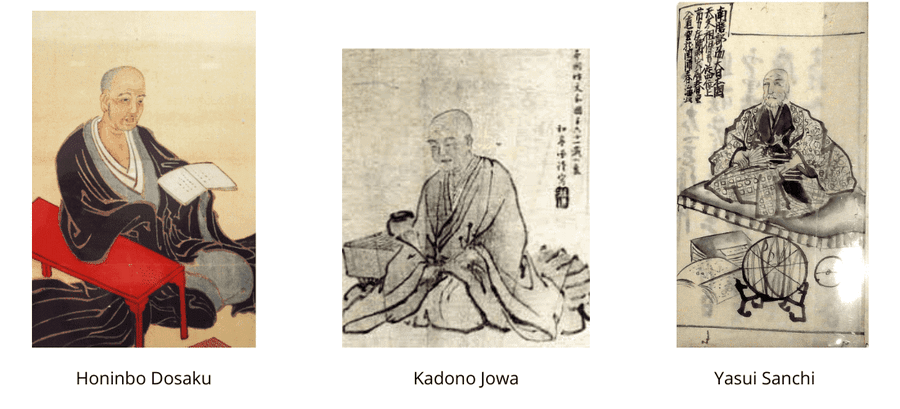

In the 16th century, under Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Japanese Go entered its golden age, marked by a nationwide tournament that crowned Nikkai as Meijin, initiating a professional ranking system. This era saw the emergence of prominent Go schools like Honinbo, Yasui, Hayashi, and Inoue, with Honinbo at the forefront. These schools played a crucial role in developing extraordinary players, bolstered by state support and approval of the highest official title, the Godokoro, responsible for overseeing Go-related activities.

Sansa (Nikkai), a monk turned Go prodigy, established a school that profoundly influenced figures like Nobunaga, Hideyoshi, and Ieyasu. The establishment of the Go Academy by Tokugawa Ieyasu in 1603 was a watershed moment: with Sansa as its head, a new wave of talented Go players was raised. This institution’s graduates became either court players or traveling teachers, spreading Go’s influence.

The Academy’s unique ranking system, developed by Honinbo Sansa, categorized players from “Shodan” (first degree) to “Kudan” (ninth degree), significantly impacting the game’s competitive landscape. This system, focusing on skill level, offered a structured approach, influencing player handicaps and ensuring an evenly matched game.

During this era, the “Go zen Go” and “O shiro Go” ceremonies were pivotal in showcasing the expertise of top Go players before the Shogun, symbolizing not only their skill in the game but also their strategic and intellectual prowess. “Go zen Go” (碁前碁), which literally means “Go before Go,” involved intricate pre-game rituals and discussions, akin to a strategic meeting before a battle. These preliminaries were crucial for players to plan their approach, discuss opening theories, and mentally prepare for the match ahead. It was an opportunity for players to demonstrate their deep understanding of Go strategies and to engage in intellectual duels even before the actual game commenced.

“O shiro Go” (お城碁), translating to “Castle Go,” was a grand and formal event held in the ornate settings of a castle or noble residence. Here, the game transcended its usual boundaries to become a part of cultural and social ceremonies, often witnessed by the elite and aristocracy. These sessions were not merely about playing Go but were also a display of cultural refinement, etiquette, and the elevated status of the game in society. Players participating in “O shiro Go” were not just competitors in a game but were also upholding a tradition that blended art, strategy, and social ceremony, making each move on the board a reflection of their grace and tactical acumen.

This period also witnessed intense rivalries for the headship of the Go Academy, a position that was highly esteemed and often held by members of the prestigious Honinbo family. The struggle for this position was not only a reflection of one’s skill in Go but also a testament to one’s standing and influence in the broader cultural and intellectual landscape of the time.

In the following centuries the standard of Go gradually improved. The proficiency level rose so much that a seventh-degree player from the modern era could be equivalent to, or even surpass, an eighth or ninth-degree player from a couple of centuries ago.

A Journey from Feudal Mastery to Global Challenge

IIn the early 19th century, Go experienced significant advancement, particularly during the Japanese Bun Kwa (1804-1818), Bun Sei (1818-1829), and Tempo (1830-1844) periods. Games from this era are still revered as exemplary, and the playing styles and opening strategies developed then continue to be studied, even though they have been somewhat refined over time.

However, with the fall of the Shogunate in 1868, the official Go Academy and the state’s regulation of Go ended. Subsequently, when the daimyos were stripped of their power a few years later, they no longer maintained the Go players who had previously served in their courts. This led to a challenging period for Go masters, who had largely depended on their craft for livelihood. Additionally, as Japan opened up to the outside world, the populace’s fascination shifted towards foreign influences, leading to a decline in interest in native traditions, including Go.

Around 1880, a resurgence of interest in Go began, reigniting appreciation for this quintessential national game. Since then, Go has been embraced with the same fervor and dedication as in earlier times, reaffirming its importance in Japanese culture.

The traditional Go schools in Japan, originally divided into Honinbo, Inouye, Hayashi, and Yasui, eventually evolved into two main schools: the Honinbo and the Hoyensha. The Honinbo school carried on the legacy of the old Academy, maintaining traditional practices and teachings. On the other hand, the Hoyensha school, founded around 1880 by Murase Shuho, was instrumental in introducing significant innovations to the game. One such innovation was the implementation of time-limited games, ensuring that no match would exceed twenty-four hours without interruption. This rule marked a significant shift from the prolonged, sometimes days-long games of the past, bringing a new dynamic to competitive Go.

Another notable contribution of the Hoyensha school was the recognition of the “Inaka Shodan” degree. The term “Inaka Shodan” translates to “first degree in the country” or “rural first dan,” acknowledging the proficiency of local players who had achieved the first-degree level in their hometowns. This recognition was crucial in acknowledging and encouraging talent outside the major urban centers like Tokyo. However, it was also a humbling reminder for these local players, as they often found themselves outmatched when facing the more rigorously trained “Shodan” players from the metropolis. By recognizing the “Inaka Shodan,” the Hoyensha school played a significant role in both expanding the reach of Go across Japan and maintaining a high standard of play, promoting continuous learning and improvement among players of all ranks.

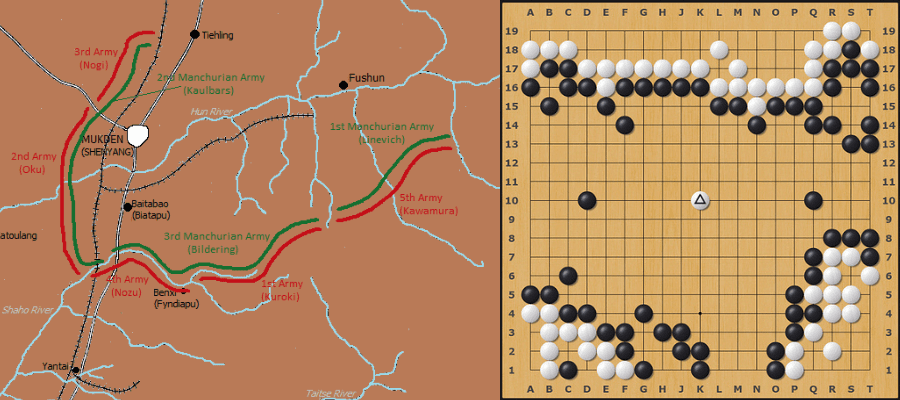

The Russo-Japanese War’s strategies were often likened to Go tactics, indicating the game’s influence on Japanese military thinking. At Liao Yang and Mukden, the battles’ strategies resembled Go’s enveloping tactics, underlining the game’s impact beyond the board.

However, Japan’s longstanding centrality in the world of Go faced challenges in the late 20th century, with the emergence of formidable players from China and Korea. Figures like Cho Hunhyun and his pupil Lee Changho dominated the global stage, leading to a shift in Go’s epicenter to these countries. Gu Li, Lee Sedol, Kong Jie, and others further cemented this shift, often overshadowing Japan in international competitions.

Go’s Global Journey: From Eastern Origins to International Acclaim

Go has been slower to globalize compared to chess, with its abstract nature and lack of climactic ending posing barriers to new players. Thomas Hyde first detailed Go in European literature in 1694. However, it was Oskar Korschelt, a German engineer, who initiated Go’s spread outside East Asia after learning from Hon’inbō Shūho in Japan.

By the early 20th century, Go had permeated the German and Austro-Hungarian empires. Edward Lasker, instrumental in founding the New York Go Club, and Arthur Smith, the author of 1908 ‘The Game of Go,’ were pivotal in Go’s American expansion. The American Go Association, established in 1935, and the German Go Association in 1937, marked significant milestones. Post-World War II, Go’s popularity surged in the West.

By the 1950s Western interest in Go was growing even stronger and in 1978 Manfred Wimmer became the first Westerner to receive a professional Go certificate in East Asia. Michael Redmond later achieved a 9 dan professional ranking. The Japan Go Association significantly contributed to Go’s global spread, establishing Go centers worldwide.

In Europe, Go’s history dates all the way back to the 17th century, but organized play only began in 1880 with Korschelt’s works. The European Championship, started in 1957, and the European Go Centre, founded in 1992, have fostered the game’s further development. British Go, with a history of over a century, saw organized play from the 1950s and has since nurtured top players like Matthew Macfadyen.

The international Go scene has evolved dramatically, with masters from Japan, China, and Korea competing in championships like the Fujitsu Cup. Amateurs also participate in global events like the World Amateur Go Championship, illustrating Go’s universal appeal.

NASA astronauts playing Go in space and the establishment of various international championships highlight Go’s evolution from an Eastern pastime to a globally revered strategic game.

Leave a comment