Mastering Defeat: How to Lose Better at Go

In Go, as in life, we share a universal tendency to celebrate our wins with far more pride than the humility with which we accept our losses. Yet it’s those very losses that expose the difficult truths about ourselves we’re often most in need of confronting. This exploration is a deep dive into a hidden realm of the game of Go, one we usually try our very best to avoid: the psychological fallout of defeat.

Introduction

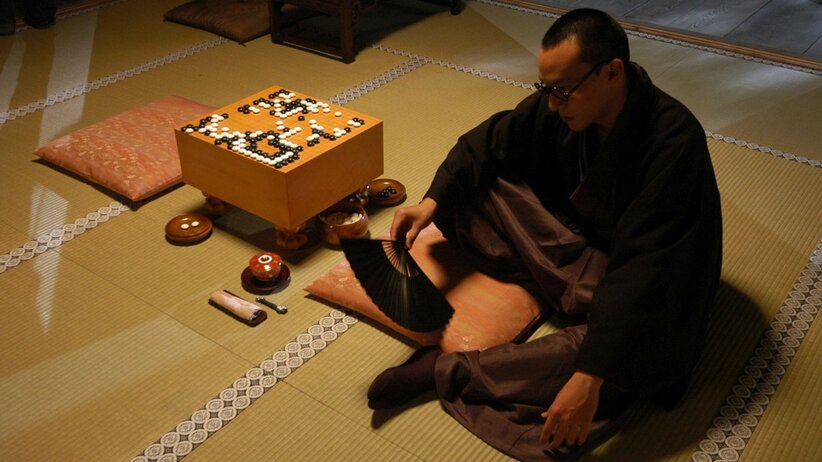

It’s a little past 3 o’clock in the morning. You’re seething at the computer screen after yet another rage-quit, your fourth, or maybe fifth loss in a row. “How could you possibly make such an obvious mistake!? Idiot.” You berate yourself. You’re exhausted, but hyper-alert. Your body is reeling from the cocktail of fight-or-flight chemicals flooding your bloodstream with every sting of frustration brought on by a regrettable move. And you’re making a lot of them. A quiet voice in the back of your head is reminding you that you have to be up for work in a few short hours, nudging you to get some rest. This voice is submerged under a surging wave of resolve, some maniacal urge to prove to “the universe” that you are, in fact, capable and worthy of ending this damned losing streak. Your finger moves automatically to click the ‘Find New Game’ button on your favourite online server….

Does This Scenario Sound Familiar?

It’s no secret to anyone who’s been around long enough that failure is an integral part of existence, whether we like it or not. Well, surprise surprise, we do not; for good reason though: Not only does evolution reward us greatly for succeeding – chemically, psychologically, socially, materially – but on the flip side, a plethora of cognitive and affective processes come together to blow our negative experience of losing way out of proportion. When these processes are amplified through multiple losses, a person may find themselves spiralling into a vicious cycle that clouds their judgment, drains their faculties and erodes their very senses, until every last bit of hope and willpower is lost.

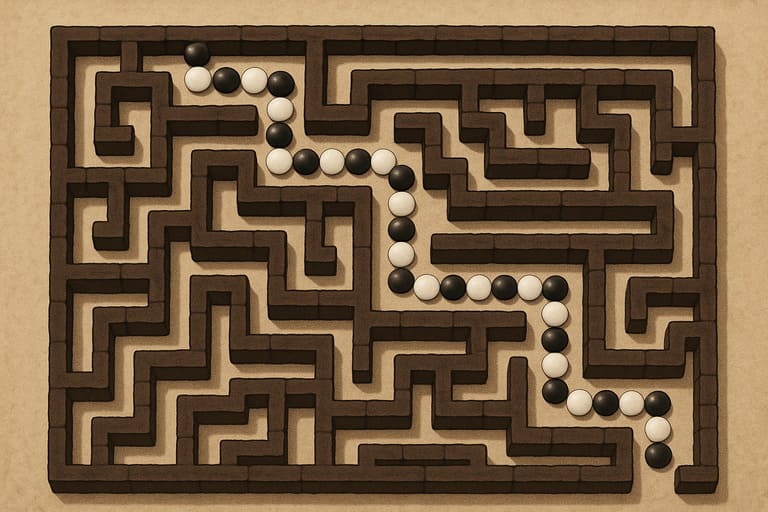

Even so, dear reader, do not despair! In this article, we will guide you through the dark corridors of the vast psychological maze generated in our minds as we experience repeated defeat, and together attempt to reach the hidden win at the heart of this difficult, fundamental aspect of Go…and life.

Dead Ends

The problem with defeat is that it doesn’t just dampen our spirits. Scientific research shows that losing triggers a full physiological stress-response: Heart rate and blood pressure climb, muscles clench, stomach churns, cortisol spikes, dopamine crashes. To your nervous system, you haven’t simply lost a board game – you’re facing a real, immediate threat. In this raw, reactive state, the mind becomes especially vulnerable to cognitive traps: biases in our thought process that covertly muddy our perception, distort our understanding, and hinder our learning. These biases are continuously at work in everyday life, subtly shaping our drives and decisions, but when we come under the stress of defeat, they exert a much stronger influence and lead us down hopeless dead ends in the sprawling mind-maze:

The Illusion of Mastery

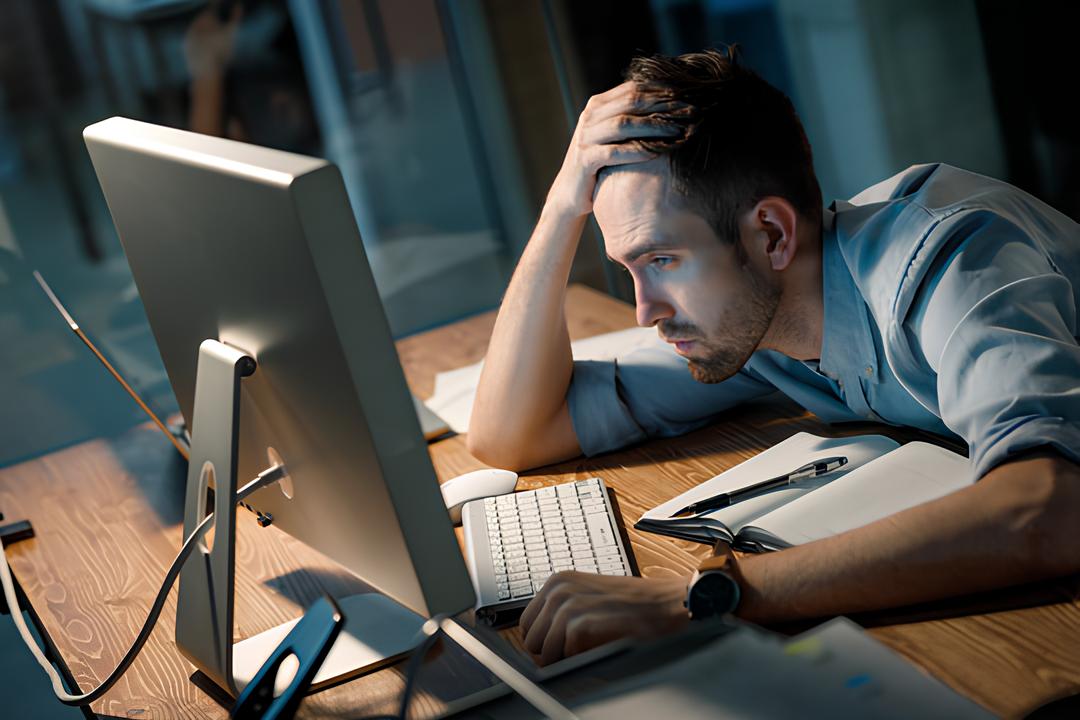

In the early stages of learning Go, you understand some basic shapes, win a few times, pick up some flashy corner tricks, and suddenly begin to think you have an actual grasp on the game; You’ve acquired just enough knowledge to feel confident, but nowhere near enough to realize how little you truly understand. This phenomenon is known as the Dunning-Kruger effect, and was first described by psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger in 1999 as the tendency of people with minimal knowledge and skill in a particular domain to widely overestimate their ability. The false sense of expertise created by this bias is often more damaging than simple ignorance, because it actively prevents us from questioning our assumptions and seeking corrections, thereby greatly impeding our progress. It takes patience, time, and effort to advance enough in the game of Go to even begin to perceive the abyssal ocean of strategy contained inside its 19×19 square grid. And while most of us will never get to explore the depths of this vast ocean, simply becoming aware of its existence can radically alter our understanding of the game, as well as our approach to playing and studying it.

The Illusion of Certainty

Once we think we understand something – especially something as complex as Go – we automatically start filtering reality through that assumption. This is confirmation bias: the brain’s tendency to seek out, interpret, favour, and recall information that supports what we already believe, and ignore and dismiss anything that contradicts it. In Go, this might look like favouring one particular joseki over the others, not because it’s the optimal choice for the actual board position, but because it worked a few times before, we’re more familiar with its variations, and now it just “feels right”; Or a player may interpret a subpar win as proof of skill, ignoring their faulty strategy simply because the opponent fortuitously failed to take advantage of it. The echo chamber created in our minds by confirmation bias keeps us trapped in the same hallway of the maze, walking in circles while convincing ourselves that we’re actually getting somewhere.

The Illusion of Commitment

You’re desperately fighting to save an endangered group. A few moves ago, it was just three or four clunky stones, nothing that important. Instead of sacrificing it for profit, taking the advantage and building elsewhere, you doubled down to rescue it, because, well, you were already committed. At this point, saving the group will not even help your overall position, but having invested so much in it, it seems like a tremendous waste to give it up; better keep on trying. This is the sunk cost fallacy: clinging to a strategy you’ve already spent considerable time and energy on despite its clear failure, pining for the past instead of playing for the future. Rationally, we know it’s better to cut our losses and move on, but emotionally, letting go feels a lot like admitting defeat, even when the former is in fact the only way to avoid the latter.

The Illusion of Value

We seem to be wired to dislike losing a lot more than we enjoy winning. In 1979, researchers Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky conducted a psychological valuation of loss in relation to gain. They discovered that the pain of a loss is felt on average twice as strongly as the pleasure of a gain, when both loss and gain are equivalent: loss aversion. This mental phenomenon creates an illusion of value: We treat what we already have as much more precious than it actually is. While this bias probably evolved as a defence mechanism to discourage risk-taking in the face of guaranteed success, it often holds us back in the non-threatening, ambition-rewarding domain of Go. Loss-averse players will cling to territory when they should be expanding and desperately attack when they should be calmly defending; They may spend multiple moves securing a few points in the corner while their opponent builds massive influence across the centre; They’re not playing to win, rather, playing not to lose.

Individually, all these biases (and many more) subtly distort our thinking, but together they compound, reinforcing bad habits and exponentially undermining our ability to succeed. Over time, these cognitive missteps affect more than just our decision-making – they begin to take a toll on our emotions and sense of self: This is where the real damage is dealt.

Suffocation

In the opening pages of his seminal book “The Direction of Play,” Kajiwara Takeo states the following:

“Every time you place a stone on the board, you are exposing something of yourself. It is not just a piece of slate, shell or plastic. You have entrusted to that stone your feelings, your individuality, your will power, and once it is played there is no going back. Each stone carries a great responsibility on your behalf.”

Master-educator Kajiwara is reminding us that the game of Go is not just about physical territory, but is played out just as much in the psychological sphere. Each move is an imprint of our inner condition, a silent disclosure of our mindset, convictions, and emotions. Unfortunately, as clarity fades and perception is warped deep in the den of defeat, the poles are reversed and it is we that start bearing the responsibility on behalf of our stones.

Each loss accrued inside the maze results in some form of lingering emotional residue: a bout of rage, a tinge of frustration, or a pang of shame that may be felt long after the game is over. Slowly, imperceptibly, this residue expands and gnarls into emotional debris that is transferred from the Go board onto our shoulders with every additional loss. Over time, this burden weighs us down so heavily to the point of reshaping our identities as players. Game results begin tethering themselves to our self-worth and shaping our sense of intelligence: Winning makes us feel sharp, capable, deserving; A simple loss may leave us seriously questioning our very worthiness of the game.

As bias and emotion seep into the deepest layers of our reasoning, they corrupt our entire decision-making process: From the micro-choices made on the board to the macro-actions taken off it, they undermine our in-game tactics and strategies and impair our motivation to play the game itself.

As the psychological effects of defeat increase and intensify exponentially, losses come to be perceived consistently as resounding proof of ineptitude, and a narrative of failure begins to take root in our psyche; While the size of the board remains unchanged, our sense of self is deformed to fit inside this twisted narrative, and our grid of possibility shrinks; We think smaller, retreat sooner, react locally, fight impulsively; Stones become vehicles of spite, ego, and fear, and our beloved game of balance and beauty devolves into a vicious, internal warfare that drives us to our wits’ end. Staggering under the weight of our losses, the walls of the maze constrict around us…

..And in the claustrophobic clutches of this harrowing mind-space, it becomes nearly impossible to conceive that there might be, somewhere, a way out.

Unravelling the Maze

Kajiwara is right in pointing out that each play reveals something profound about the player. But caught inside the maze, our thrashed, bias-ridden ego feels attacked by this simple truth and interprets it as a judgment of character: “If I truly am what I play, then every blunder is a personal failure, and every loss is the result of some incurable inner flaw.” But Kajiwara is neither inciting us to give in to passion nor to betray our self-image. It’s not his fault if we misinterpret his words and conflate the innate strategic weight of a stone with the assumed psychological burden of its player. Beneath its solemn cautioning, his message is shockingly simple: Pay attention, play with intention; Observe yourself, observe the game.

That’s it.

With these directives, the maze seems…different. It still stretches out all around us, but it’s somehow less menacing, its walls and corridors a little less constricting.

As we begin to actively observe rather than passively react, an interesting change occurs: Everything slows down; we suddenly have time to reflect. It’s not that we never had the time before, but by blitzing away at the speed of our emotions, we simply forgot that we were allowed to use it. And what a revelation. In this unhurried, deliberate state, novel behaviour emerges: We begin to examine our thoughts more closely, identifying our impulses and experiencing them as passing events instead of binding commands; we begin to tolerate uncertainty instead of rushing in to resolve it; we take note of the space between moves, the silence between the notes of this curiously musical game.

As our internal pacing slows and the relentless chatter quiets down, the emotional fog clouding our decisions gradually dissipates, and a clearer view emerges. We begin to notice patterns in the layout of the maze: For the first time, we see how our biases have been misleading us in the form of fake clues etched into the walls, masquerading as guidance and steering us into dead ends; we recognize the looped pathways of circular reasoning that perpetuated and sustained our illusions of progress, all the while feeding our doubts and self-berating tendencies; we spot the baited traps of false urgency that tricked us into cognitive overload through rushed decision-making. And with each new pattern uncovered, a measure of agency is reclaimed. Our minds come out of their autopilot-haze into the refreshing clarity of focused attention. In this newfound clarity, we find that we can move around the maze more easily. We trace it lucidly rather than stumbling around blindfolded, carving out a new path for ourselves through its corridors.

While we continue to experience frustration from our blunders and disappointment at our losses, the urge to act on these emotions is losing its potency; we place increasing trust in the firming voice of reason guiding our stones; we recalibrate our valuation of each move’s place within the game: not just another blob on the black and white canvas, but not an immutable expression of our self-worth either; nothing more, or less, than a careful act of mindful engagement. From this balanced perspective, our biases loosen their grip on our minds, our faculties sharpen, and priorities snap into focus; we find ourselves reading deeper, estimating more accurately, and anticipating weaknesses before they appear; we pause where we would have lunged hastily at local gains; we carefully turn over strategies in our heads without spiralling into anxiety and desperation.

This mental state of equilibrium that we gradually settle into results in an acute awareness of our own fallibility, and deeper insights follow: We stop interpreting each blunder as a personal calamity and each loss as a verdict on our integrity; desperate, ego-protecting habits like clinging to hopeless positions and stubbornly refusing to resign give way to flexibility of thought and dignified composure; the errors that previously felt like accusations are now relevant feedback, and we engage with defeat as valuable information rather than rejecting it as a shameful affliction. In this optic of acceptance and curiosity, winning becomes less about reclaiming our allegedly stolen dignity and more about deepening our understanding and appreciation of the game. The former is no longer a validation of our worth, but simply one side of an ongoing conversation, in which the losing end is just as engaging.

As we come to embrace our losses in light of the hidden learning potential embedded inside our mistakes, the very nature of defeat transforms: The maze is no longer a trap, it has become a teacher. We revel in the powerful realization that every time we lose a match, we gain the insight of a formidable master.

Centered Grace

In the Dao De Jing, sage-philosopher Laozi writes:

“To attain knowledge, add things everyday. To attain wisdom, remove things every day.”

In the West, personal development has historically consisted of a vertical climb toward mastery through the stockpiling of knowledge, expertise, and intellectual sophistication; the idealized self is erudite: filled with facts, armed with technique, fluent in logical reasoning. Growth, in the western mind, is a cumulative process, with information as its core currency.

The ancient culture from which the game of Go emerged, on the other hand – steeped in Taoist, Confucian, and Zen Buddhist traditions – offers an antithetical model of progress. In the Eastern model – and Zen specifically – wisdom comes not from filling our heads with facts and figures, but only after emptying it of them; we attain clarity by relinquishing control over our thoughts, not by beating them into submission; profound insights are experienced not by building layer upon layer of external concepts, but by shedding all pre-existing notions about the very nature of reality. “To hold, you must first open your hand,” says counterculture pioneer Timothy Leary. This is the paradox of Zen: The real gains in life can only be won through losing.

By surrendering our ego and accepting loss as the path itself and not an insufferable detour, the corridors of the maze open up like the petals of a flower caught in a ray of sunlight: The master is inviting us to sit at their feet and learn from them. Who would have thought that the key to the maze would be as simple as accepting it as a mentor?

And yet, simple does not mean easy.

Anyone can find balance momentarily – it’s easy to walk a tightrope for a few seconds, to stay focused for the first few moves. Staying centered for the length of an entire game, let alone a lifetime, is something else entirely because balance is not a one-time achievement, but a constant, continuous returning. Even after reaching the centre, we can still lose our footing and stumble back into the confusing corridors of the maze. As the cheeky Zen proverb tells us: “Before enlightenment, chop wood, carry water. After enlightenment, chop wood, carry water.” The real challenge is not in finding the path, but in walking it gracefully, over and over and over again.

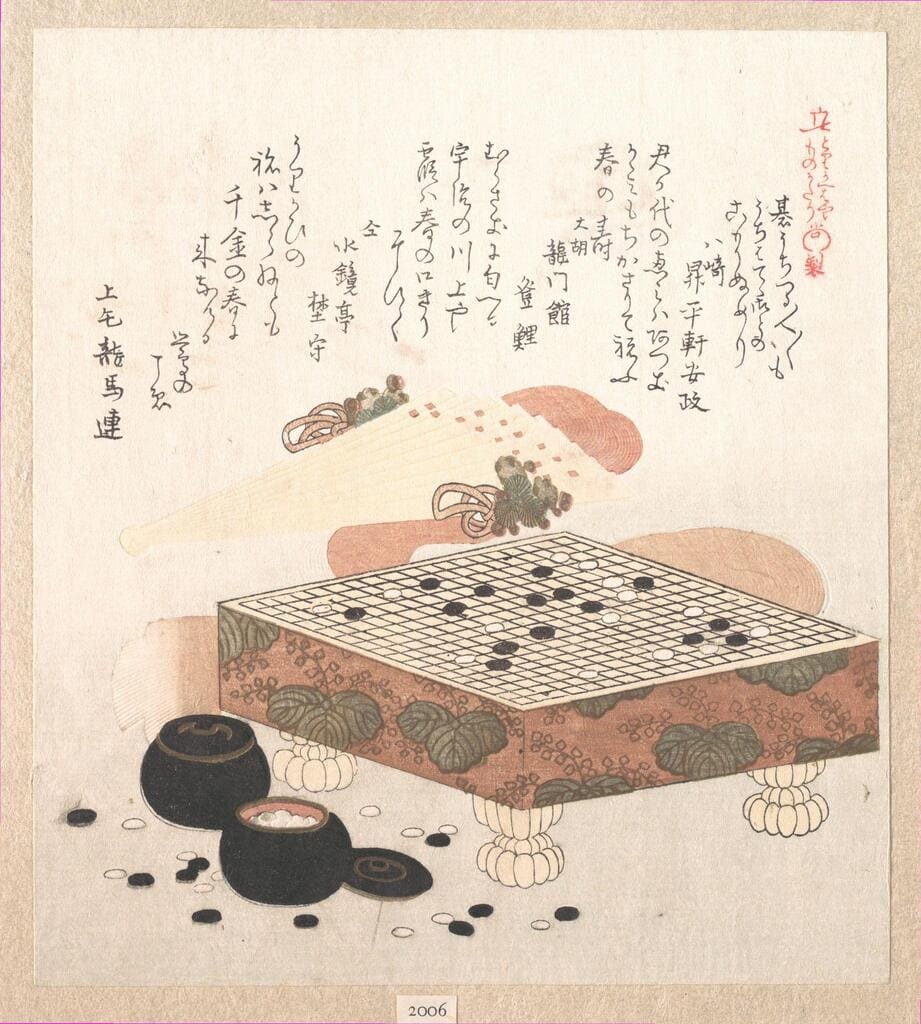

This is why the practice of Zen is so central to the game of Go: It’s a discipline that enhances our flow of awareness and deflates the ego’s ambitions by dissolving the barrier between path and goal. Instead of chasing outcomes and accumulating achievements, we simply engage the present moment as fully as we can, and patiently allow the pressure washer of direct experience to scrub our minds clean. Zen teaches us to cultivate patience – but just as importantly, humility. When a great master shows meekness at the Go board, it’s not out of false modesty, but genuine reverence for the game’s infinite depth as a microcosmic mirror of life. This mindset of humble respect so deeply embedded in the Eastern view of Go acts as a powerful antidote to the cognitive distortions that so easily hijack the ego to cloud our judgment, pollute our play, and hinder our progress.

But we have much, much more to learn from the Eastern masters, and stronger players in general, besides humility: Focus, restraint, tenacity, and equanimity are just a few of the values the best of the best actively seek to embody in all aspects of their lives; and the lifelong habits cultivated as a result of these deep-rooted values transfer directly to the Go board as real, tangible skill: Strong players build flexible, multipurpose shapes and create miai as much as possible (a situation where two moves hold equal strategic value – whichever one the opponent chooses, we can play the other without incurring a disadvantage); They’re adept at sacrificing, settling groups, and exploiting aji (weaknesses) at exactly the right time; They consider multiple strategies at every turn and read deeply before committing; They prioritize whole-board thinking over local positions because they see the board as a single, organically transmuting shape.

But perhaps the singular most important trait shared by all these players is their raw, stubborn dedication. When the legendary cellist Pablo Casals was asked why he continued to practice 4 to 5 hours a day at the ripe age of 90, he replied matter-of-factly: “Because, I think I’m making progress.” If there’s one thing exceptional players are continuously doing, it’s improving. And no matter your expertise, aptitude, or mental makeup, the fastest, surest way to do so is through good ol’ dedicated studying. Top Go professionals are known to study the fundamentals religiously and relentlessly, most beginning as young as possible and some maintaining a staggering pace throughout their entire lives. To be clear, we’re not asking you to solve life-and-death problems and review games for hours on end every day for the rest of your life (unless you’re aiming to become professional, in which case see the video below).

However, a fixed schedule of some form of cognitive practice of as little as 15 minutes a day has been scientifically proven to not only boost a person’s skills in the particular activity, but to actually accelerate skill acquisition, strengthen memory, and improve mood. These extra enhancements both help us win more and help us learn more efficiently from our losses. That’s a lot of wins.

For the Zen practitioner, however, practice is never the means to an end such as winning; It’s simply an attuned state of awareness. Zen master Shunryū Suzuki tells us that the point of practice is not “to sit to acquire something; It is to express our real nature.” Suzuki is talking here about the practice of seated meditation, but his words are just as apt for the Go board. When we approach the game with presence, humility, and acceptance, not to prove anything, but simply to express our inner truth, we begin to embody the real meaning of both Zen and Go: that mastery is not measured in victories, but in the grace with which we meet defeat. This is the hidden win at the heart of the maze.

Conclusion

Losing is as inevitable in Go as it is in life. No matter your level – star-eyed neophyte or seasoned veteran – you will lose, often painfully, sometimes repeatedly. And unlike many other games, where defeat can be brushed off as bad luck or lousy mechanics, the Go board is a cold, hard, reflective surface of our inner state, every stone a vivid imprint of our intentions, ambitions, and habits of mind. Conversely, the intellectual and psychological depth of the game provides an ideal breeding ground for cognitive biases to thrive in the form of false certainty, misplaced loyalty, and other ego-driven behaviour, and all it takes is a few frustrating losses for these biases to take root and compound. Fuelled by increasingly emotional responses, they trap us inside loops of anger, doubt, and despair, until we fall deep into the digestive tract of the mind-maze and get swallowed, chewed up, and spit out on repeat.

Fortunately, and somewhat ironically, the way out of this circular prison is as simple as paying sustained attention to its underlying structure, as simple as observing the very fabric of the bars that deny our minds’ freedom. And the inevitable paradigm shift occurs when we finally accept our blunders as signposts dotting the uncharted path of our educational Go journey, and loss as the compass guiding our way.

Perhaps it’s no coincidence that the gentle discipline of Zen proves so effective on this personal journey. By illuminating the beauty and potency of the present moment, Zen teaches us to fully embrace its impermanence while cultivating lasting awareness. Through its practice, we learn to flow with the rhythm of the stones, adapt with clarity, and grace our misses with calm acceptance. And in this way we grow, not despite our losses, but thanks to them.

“Mastery is not measured in victories, but in the grace with which we meet defeat.”

Could have started and ended the article with just that, but well done, a very nicely crafted in depth article on the demons we all face, falling in love with and cursing at the same time this beautiful game.

Thank you Malakia! Indeed, all part of the Go journey :))

Beautifully written and incredibly helpful!

Thank you Jamie!

What an interesting article! I find it very useful not only for improving as a Go player, but also for building a better way to look at the thinhs that happen in your life. I personaly think that the mindset that requires mastering in a game like Go will not only make you a better player (which is obvious), but also a better person and a wiser one, which may not be that obvious. Anyway, thank you for thr article, I really enjoyed reading it and learning from it!

You’re very welcome! it’s really all in the mind 🙂