Learning from Pro autobiographies #3: Outside the Board: Diary of a Professional Go Player by Lee Hajin (a.k.a. Haylee)

“I have a theory that Go players are all good people. Playing Go means one learns how to accept one’s own mistakes and defeats, how to reject opponents and admit the fact that no one can win every time.”

Introduction

Hajin Lee, known internationally as Haylee, is a pioneering figure who bridged the gap between the elite world of Korean professional Baduk and the global Go community. As one of the first strong female professionals to build a massive following through YouTube and online teaching, she demystified the game for a generation of Western players with clarity, warmth, and intellectual honesty. Her autobiography, Outside the Board, is not a chronicle of legendary titles or epic rivalries, but something rarer: an intimate, candid diary from the trenches of a professional’s life. Compiled from her online posts, it pulls back the curtain on the immense psychological pressures, personal insecurities, and the ongoing quest to find balance between a consuming passion and a fulfilling life.

Hajin Lee Interview on All Things Go #Podcast for Go Magic

The Inner World of a Professional Player

Hajin Lee’s autobiography reads differently and fresh. The author, a Korean female professional 4 Dan, is known in the West more as her alias, Haylee, one of the earliest strong Youtube Go streamers. Through hundreds of hours of her videos, she taught generations to approach Go with clarity and intellectual honesty, forging an almost intimate connection—one that transcended the asymmetry and distance of the digital realm. Similarly, her unconventional autobiography is candid, authentic and true to life. Her book emerges from the collection of posts from her at starbaduk.cafe24.com where she sought to describe to an English speaking audience thin slices from the life of a female professional Korean Baduk player.

Hajin Lee pulls back the curtain on the often-romanticized image of a professional Go player, revealing a landscape filled with surprising vulnerabilities and pressures. Many Go players might imagine top pros as unshakably confident, but Lee shares her deep-seated insecurities, particularly the fear of losing terribly or being judged as “not as strong as expected.” This fear was so potent that it sometimes made her avoid playing outside official matches. She admits that the words that would hurt her most relate to her perceived skill level, illustrating how a pro’s identity can be deeply intertwined with their performance, making any criticism feel like a critique of their entire life’s work:

“It’s ironic that I am insecure about my baduk skills when I am stronger than most people in the world […] When my baduk skills are criticized, I feel my whole life is being criticized and there is nothing good I can do. Rationally I know this is not true, but it’s hard to change how I feel about it.”

The emotional toll of high-stakes Go is another raw element Lee doesn’t shy away from. She recounts crying for days after a particularly painful loss in a pro qualification match, a stark reminder that even seasoned players grapple with profound disappointment. Interestingly, as she matured and her life broadened with university studies, her perspective on winning and losing evolved. She found that focusing on playing a “good kifu” (game record) rather than solely on winning not only reduced pressure but also improved her performance. This shift highlights a mature understanding that true satisfaction can come from the quality of play itself, a lesson many amateurs striving for rank might overlook in their pursuit of victory.

This honesty about insecurity and emotional struggle is a unique teaching. While many pros talk about fighting spirit, few delve into the personal anxieties that can cripple or, paradoxically, motivate. Lee’s journey suggests that acknowledging these inner battles, rather than denying them, can be a path to a healthier and perhaps even stronger relationship with the game. After losing more than 100 important games, Hajin admits that she only cries less frequently, only for the most crucial ones, but also laments the fact that our body never develops immunity to defeat.

Hajin Lee’s journey reveals a profound shift in what constitutes a “meaningful” game, moving beyond the raw desire to win towards an appreciation for the quality and integrity of her play, symbolized by the “kifu” (game record). Initially, Go was “like a war,” and the idea of focusing on a “good kifu” over victory seemed “boring.” However, with experience, she came to realize that “playing poorly hurts my pride more than just losing the game.” This marks a critical evolution: the game record becomes a testament to her effort and understanding, a source of intrinsic satisfaction or deep disappointment independent of the result. Her insecurity about being perceived as “not as strong as expected” underscores how deeply her identity was tied to the quality of her demonstrated skill. Later, as her life broadened and the acute pressure of survival in tournaments eased, she found herself choosing “interesting” moves over “proper” ones, indicating a newfound freedom for self-expression on the board. This transition from Go as a battlefield where only victory matters, to Go as a canvas where the artistry and intellectual honesty of the “kifu” hold immense weight, is a unique insight into the maturation of a professional player.

Go Requests Effort

Hajin’s account of her Go education offers several unique insights into what truly shapes a strong player, moving beyond rote memorization of joseki. Her childhood obsession with Life & Death (L&D) problems, to the point of neglecting other areas, is telling. This passion led to a unique and rather severe training method from her teacher: memorizing entire L&D books without answers and facing a physical punishment (holding a board above her head) for each mistake. While perhaps extreme, this underscores the intense focus and dedication required, but also her personal affinity for the “pure” logic of L&D.

Although Hajin shares with the reader the hidden intense emotional landscape of the professional player, she suggests that psychological shortcomings can be corrected through effort and dedication. One of the most insightful teachings is her discussion of “wishful thinking” in Go. She pinpoints how players, especially when facing those they perceive as weaker, often fail to see simple solutions because they expect their opponent to miss things, or they believe their superior strength will magically resolve a situation. This cognitive bias, she suggests, is a major culprit in losing “won” games. Her advice is direct: L&D skills are purely up to the individual, as answers are absolute and resources plentiful, so be wary of wishful thinking and practice diligently.

Hajin uniquely draws parallels between studying Baduk and learning a foreign language: both require a balance of formal study and practical application (“you have to do both”), a mastery of fundamentals (“players who understand shapes and the flow of stones can navigate any stage”), and an awareness that anxiety invites mistakes. All of these require considerable effort and no one who wants to become stronger is exempt from it.

Hence, Hajin presents us with a careful accounting of the 21,000 hours she put into becoming a pro – studying Go every day from 2 p.m. to 10 p.m. during school days, and 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. on school vacations. For us amateurs, she provides a conceptual formula for getting better at Go.

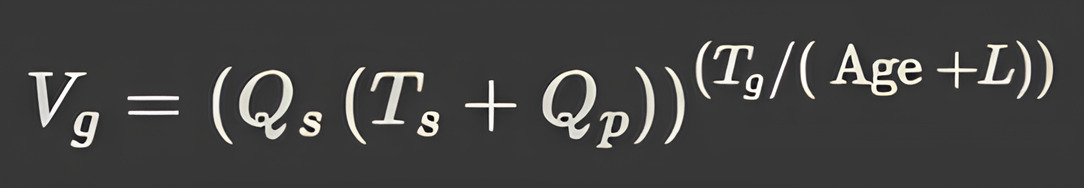

Hajin’s Baduk Formula

- Vg: Speed in improving your baduk skills

- Qs: Quality of sources (teachers, books, playing partners) → 1 to 5 scale where 5 is extremely good

- Ts: Time of study → Average time you are investing a day (1 point for 5 minutes)

- Qp: Quantity of playing → Average number of games you play a day (5 points per game)

- Tg: Natural Talent in Go → 1 to 5 scale where 5 is as talented as professionals

- Age: A player’s current age

- L: A player’s current level of Go → 1 to 30 scale where 7D is 30

Hajin warns us that the formula is only for fun and not a scientific tool. She even gave us an example — if you are 30 years old and 2d, studying 30 minutes a day, playing one game a day with a moderate quality of books and partners, you would be improving at the speed of 48 per day. Starting from this example we made a plot, also for fun.

Although the formula has no empirical support, we can still make some inferences concerning the parameters viewed from Hajin’s perspective. Playing games and studying are equally important and equally dependent on quality of learning material or quality of partners. Natural talent speeds up improvement but this gets slowed down with age and rank. But the key takeaway of the graph is that doing nothing is unforgiving, while doing a little each day (e.g. 1 game and 5-10 min of study) leads to large improvements.

The Shifting Relationship with Go: Balancing Life and the Game

A prominent and unique theme in Hajin Lee’s reflections is her evolving personal relationship with Go, particularly the journey of balancing an all-consuming professional career with other life pursuits, like university education. She candidly describes how, for most of her early life, Go was her singular focus, involving immense dedication and sacrifice. This intense immersion is common for aspiring professionals, but Hajin’s subsequent path offers a less-traveled narrative.

The decision to fully attend university marked a dramatic shift, where Go was no longer her “top priority.” This wasn’t an abandonment of Go, but a recalibration of its place in her life. This quest for balance is a profound teaching, especially for serious amateurs who might struggle with Go’s demanding nature alongside other responsibilities. Lee’s experience suggests that stepping back slightly can, paradoxically, rejuvenate one’s connection to the game. She found herself taking more risks and enjoying play more when the desperate need “to survive in tournaments” lessened.

This nuanced perspective—that Go can be a part of a fulfilling life rather than its entirety, and that this balance can bring new joys to the game—is a valuable lesson often missing from narratives focused solely on achieving peak competitive strength. It’s a mature recognition that one’s identity can be more than just “Go player.”

Rekindling her passion for the game, she produced what the author of this article considers to be one of the most thoughtful list of reasons to play Baduk. She lists 25, but we will spoil only 3:

- It’s a sustainable game. Financial or physical hardships won’t affect your ability to enjoy this game.

- It teaches you that there can be more than one answer.

- In order to be a strong player, you need both logical and emotional approaches to solve problems in actual games.

Game: Unlikely Media Celebrities Clash in the 3rd Korean GG Auction Cup

In the appendix of her autobiography, Hajin presents multiple games together with light commentary. Her initial victories and subsequent defeats against top pros Rui Naiwei and Cho Hyeyeon within important female tournaments are well known. Here we chose to present a game against a player that stands out in an unconventional way, similar to Haylee herself. She candidly reports in her emotionally evocative journal narratives that she was “thrilled and worried at the same time” to play against Jimmy Cha, a player she knew since she was 15 years old for being the inspiration of an extremely popular TV show in Korea.

Jimmy Cha is multi-talented black belt in martial arts and classical pianist, but most surprisingly throughout his life he mixed being a professional Go player with being a professional poker player. The South Korean television drama series All In (2003) was inspired by the poker side of Jimmy Cha’s life, but his Go career was equally awe inspiring. So much so that his story is briefly featured both in Lee Hajin’s autobiography but also in Cho Hunhyun’s. Interestingly, both Jimmy Cha and Hajin Lee emigrated from South Korea and became United States citizens and both remarked themselves through unconventional creative means.

Jimmy Cha is an extremely rare, living exponent of a dichotomy insightfully outlined by Haylee. While presenting regulatory and insider perspective aspects of being pro, she reflects on the fact that in East Asia, being a professional Go player is like earning a Ph.D. – a prestigious title you keep until you decide to retire. Yet, since there is no reason to retire, this becomes a life-long profession. Conversely, in the West, “professional” means making a living from the activity, so even skilled unpaid players are seen as amateurs. Thus, unlike Go, poker has no formal test – players are considered professional if they compete at high levels and earn money. Like the contrast between black and white, Jimmy was a professional according to both standards, while Haylee chose to retire from holding the otherwise life-long honor of being a Go pro.

Their game was played on April 29, 2009. Jimmy Cha (5P) was White, Lee Hajin (3P) was Black.

Conclusion

Hajin Lee’s autobiography offers a quiet but profound revolution in how we view professional Go and our own relationship with the game. While the legends we often study, like Cho Hunhyun or Chen Zude, show us the path of unwavering, singular dedication to competitive excellence, Lee charts a different, equally vital course. She reveals that the professional path is not just one of relentless pursuit, but also of introspection, vulnerability, and the search for a multifaceted identity. Go is unfathomably, stupidly vast, but we as human beings are vaster still.

The core of Lee’s teaching is that Go is a dialogue with oneself. Her evolution from seeing Go as “a war” to valuing the “good kifu” is a masterclass in shifting from extrinsic validation to intrinsic satisfaction. This mindset—where the quality of your effort and the honesty of your play become the true measures of success—is a liberating lesson for players at any level. Furthermore, her “Baduk Formula,” while playful, underscores a serious truth: consistent, daily engagement, no matter how small, is the engine of improvement. It demystifies progress, placing it within the grasp of any dedicated amateur.

Ultimately, Outside the Board is a testament to balance. Lee’s decision to embrace university and other interests did not diminish her as a player; it enriched her as a person, which in turn refreshed her approach to the game. Her list of 25 reasons to play Baduk, born from this rekindled passion, serves as a powerful reminder of the game’s enduring gifts: its sustainability, its embrace of multiple truths, and its unique demand for both logic and intuition. Hajin Lee’s legacy, both in her streaming and her writing, is one of authentic connection. She shows us that the true mastery of Go is not just about conquering the board, but about understanding oneself, and that sometimes, the most important lessons are found not in the center of the fight, but in the spaces we create for ourselves outside of it.

Leave a comment