Learning From Pro Autobiographies, Part 2: Go with the Flow – How the Great Master of Go Trained His Mind by Cho Hunhyun

“The only thing that should be on the mind when playing Go is where to play. One must concentrate all the mental strength to figure out the positions on the game board. In real life, likewise, one must appreciate the present. Be in the moment because it will never come back again. Every dream begins ‘right here, right now.’”

This is the second part of the series. The first part can be found here: https://gomagic.org/ru/striving-for-excellence-by-chen-zude/

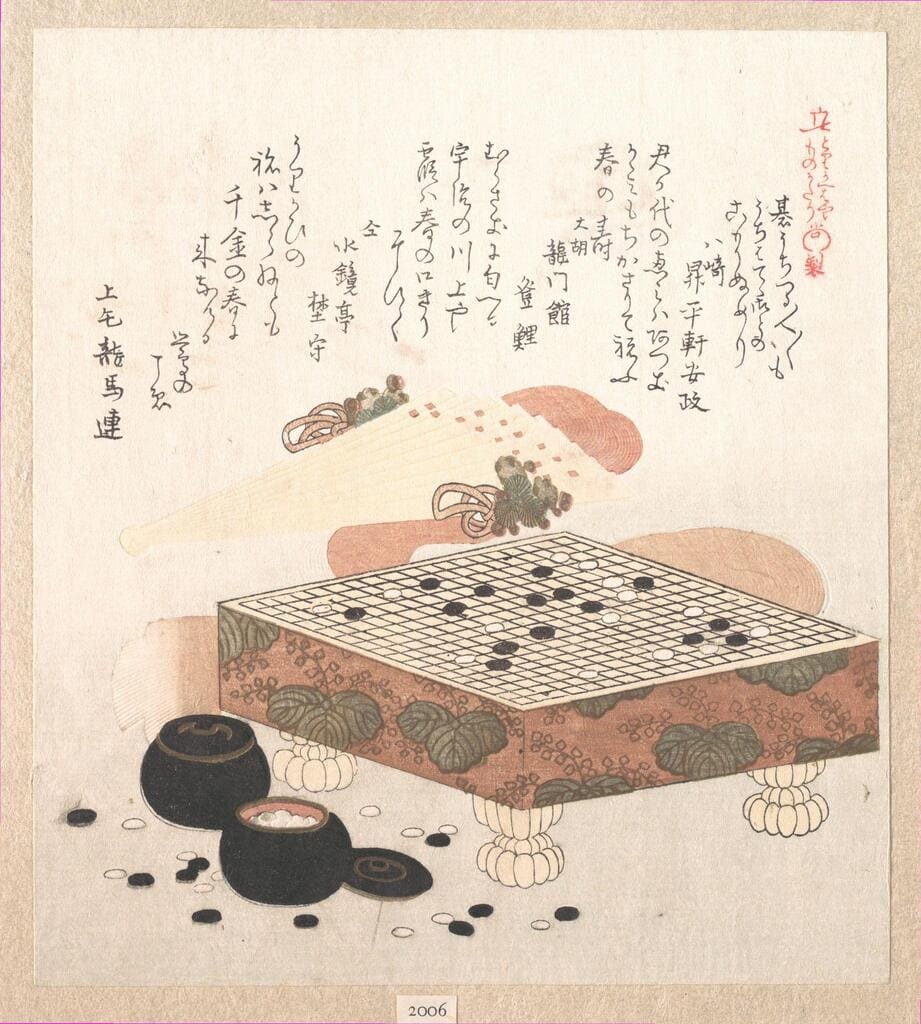

Introduction

Cho Hunhyun is a titan of the modern game whose legacy is inextricably linked to the rise of Korean Go on the world stage. His career spanned an era of profound transformation, from the post-war dominance of Japanese players to the fierce international rivalry of the late 20th century. Cho greatly challenged the common wisdom in Go, was a stylistic chameleon with ever-evolving ways of play and his legendary mentorship of Lee Changho created one of Go’s most defining rivalries. His autobiography, however, offers far more than a chronicle of titles and famous games; it is a profound meditation on the cultivation of a master’s mind.

Written with the reflective clarity of a player who has faced both pinnacles of victory and abysses of defeat, Cho’s narrative explores the philosophical underpinnings of true mastery. His life story becomes a compelling argument for a core truth: that Go is not merely a game to be won, but a medium for self-discovery. As in life, true genius lies not in learning all the answers, but in having the courage to find your own.

Mentorship

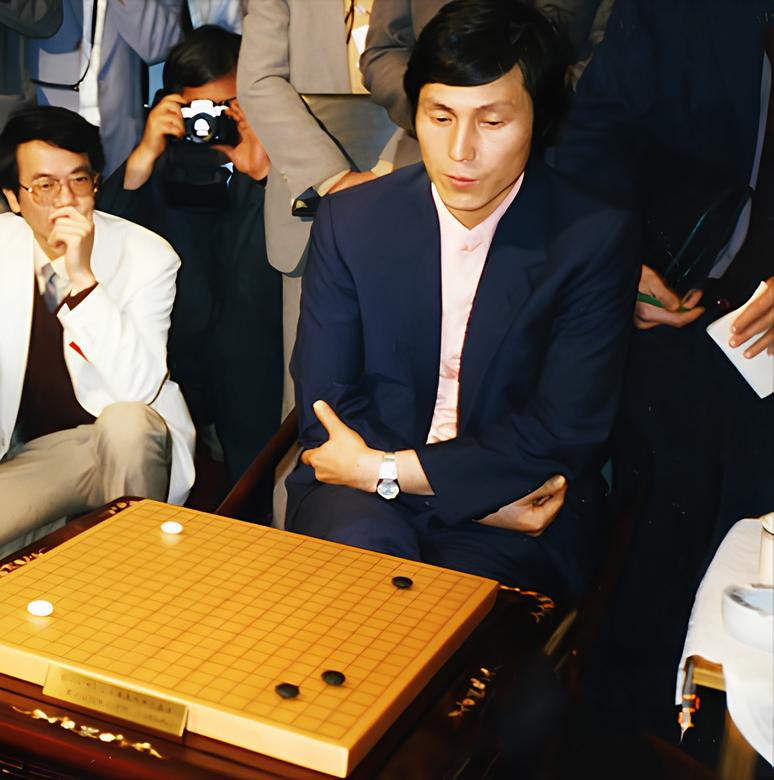

Cho Hunhyun, as he himself attests, had no formal training in Go. He was a Go prodigy, from the age of five defeating adults with ease and becoming the youngest professional Go player in the world at age nine.

Cho Hunhyun’s greatest lesson came from what his mentor refused to teach him. Master Kensaku Segoe was a recluse who only welcomed one guest, the Nobel Prize winner Yasunari Kawabata (author of The Master of Go). Nevertheless, he shaped legends of all three kingdoms—Go Seigen (China), Utaro Hashimoto (Japan), and Cho Hunhyun (Korea). Master Segoe never corrected Cho’s moves. At dinner tables and training sessions, he offered only silence or the same maddening refrain: “There are no such things as answer keys in Go.” Forced to wrestle alone with each problem—sometimes staying up all night for a single move—Cho developed something rare: a mind that trusted its own creativity over convention.

Yet Segoe’s philosophy extended beyond technique. He believed true mastery demanded character forged through failure. “Those used to feeling flattered from winning are not able to bear being defeated,” he warned. By withholding praise and forcing Cho to lose—and lose again—he hardened his pupil for a career where titles would rise and fall like stones on a board. Even in Cho’s later years, mentoring Lee Changho, their relationship echoed Segoe’s method—no comforts, no shortcuts, just the cold clarity of the game.

For modern players drowning in tutorials and AI analyses, Segoe’s approach may seem archaic. But his legacy whispers a radical truth: Go’s deepest answers aren’t taught—they’re unearthed in solitude.

The Gamble: Cho’s Bets in and for Go

Cho Hunhyun’s journey underscores a recurring theme in Go and life: the danger of prioritizing immediate rewards over enduring mastery. As a young professional under Master Segoe, a single instance of playing Go for a mere 600 yen—an act of gambling strictly forbidden by his mentor—led to his expulsion. This transgression nearly ended his career, a stark reminder that, as Master Segoe’s principles implied, one should “never put skills and knowledge before virtue.” This experience of nearly losing everything over a small, impulsive gamble shaped his understanding of risk and reward.

Cho’s later wisdom extends to the board itself. He warned, “A Go master never becomes too excited when a position that can bring immediate advantage comes into view. The opponent would have probably seen it too and must have already braced to take a counter action. Throwing oneself into what looks appealing now could result in a dire loss later.”

Nevertheless, decades later, as traditional Go lost ground to digital entertainment, Cho made another calculated risk. He became the public face of Batoo, an online Go variant which included exciting combat-style factors and gambling elements. Critics accused him of chasing money or compensating for declining skills, but his true motives focused on increasing Go’s popularity even at the cost of taking a blow to his reputation. Though Batoo failed, he refused to deem it a “bad move.” Like a sacrificial stone that opens future opportunities, he stood by his choice: “just because the outcome wasn’t what I envisioned doesn’t mean it was wrong.” For Cho, true mastery meant balancing discipline with daring—whether resisting temptation or embracing it for Go’s sake.

Cho’s Commandments

Cho’s selection from ‘Ten Commandments’ (by Wang Jeoksin, designated Go adversary to Emperor Xuanzong of Qing Dynasty, China) tells us giving up is necessary. Cho commands us to “release oneself from the things that tie one down […] Lighten the body and the mind to travel faster, longer, and further.”

- 5th Commandment: “Don’t trade a dollar for a penny.” (Sacrifice small gains for bigger victories.)

- 6th Commandment: “When in danger, abandon stones.” (Know when to cut losses.)

- 10th Commandment: “Seek harmony when isolated.” (If outnumbered, negotiate survival.)

Go’s Flow: the Evolution of Styles

Cho reflects on several famous games. The 1938 retirement game of the last hereditary Honinbo – Honinbo Shusai versus Kitani Minoru that lasted for 158 days is used to reflect on the race against time in modern games. The 1986 Kisei Title Match where Cho Chikun showed up at the finals versus Kobayashi Koichi in a cast and wheelchair gives opportunity to think on the refusal by both parties to make excuses for themselves. Still, the main games of the book are those played by Cho himself which force us to contemplate the ever-evolving styles.

Cho’s early ‘Swallow’ style danced on the edge: light, sharp, leaving groups dangling while seizing territory elsewhere only to return and narrowly escape death. This style ruled over the Go world and also molded the mentor-mentee relationship with Lee Changho who could never defeat his master’s unexpected aerobatic maneuvers. Adapting, Lee Changho’s impenetrable calm style of the ‘Stone Buddha’ eventually clipped the Swallow’s wings giving rise to one of Go’s most emblematic rivalries.

Cho reinvented himself as the ‘God of War’—a flame-thrower who balanced aggression with patience. Still, the ‘Stone Buddha’ aimed to win by 0.5 points 100% of the time. In their matches, Cho won by half a point 5 times, while Changho won by half a point 20 times. Cho eventually lost all of his titles to Changho, and Changho lost his to his junior, Lee Sedol. Sedol was to face tough challenges from his junior players. The cycle was inevitable: no style reigns forever. Cho observes with serenity the essence behind this perpetual flow: “How a player chooses to see the world is what determines the style and approach of the play. It is also how they choose to live in the real world. So a match between two rivals is a clash of two different sets values.”

Game: Challenging convention by playing ‘empty triangle’ twice in the semi-finals of the Ing Cup

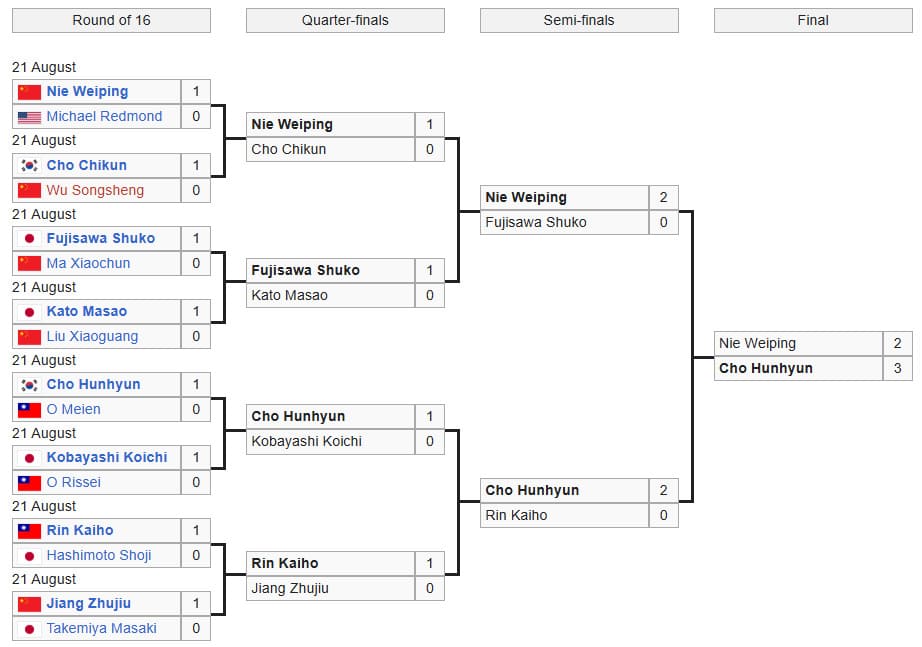

China already established themselves as worthy contenders in the “Go sport”. Now at long last Chinese top professionals could rival those of Japan, but Koreans never came close.

The 1st edition of the Ing Cup sponsored by the Chinese industrialist Ing Chang-ki was a truly international event with an enormous prize of 400,000 dollars for the winner.

The Chinese expected Nie Weiping, Chen Zude’s successor we mentioned in the prior autobiography, to win it and bring glory to the Chinese state. Nie Weiping, was on a 11 game winning streak in the first three tournaments playing against top Japanese players. Then history happened. Korea through the hand of Cho Hunhyun ever so unexpectedly rose to the occasion and conquered this first colossal title.

The fifth deciding game of the Ing Cup final between Cho Hunhyun and Nie Weiping remains in the annals of Go. In his autobiography, Cho Hunhyun shares how it felt from the inside. We still marvel at the 129th move made with only 10 seconds to spare changed the tide of the game and got Cho Hunhyun the win. People still ask about it, Cho Hunhyu answers “I have no idea. I still don’t know […] All I did was to surrender myself to the forest of my thoughts. I didn’t find the answer. My thoughts led me to it.”

Nevertheless, move 129, as emblematic as it was, must wait for another time, while we will present another happening from the semifinals of 1st Ing Cup. In the semifinals Nie Weiping of China defeated 2-0 Japan’s Fujisawa Shūko, while we will focus on the mirror 2-0 victory of Korea’s Cho Hunhyun versus Taiwanese-born Rin Kaihō (or Lin Haifeng using his Chinese name referenced also in Chen Zude’s autobiography). In the first of these two matches, Cho won with White by playing two times the infamous empty triangle. The first was played at move 72, the second at move 186.

“Empty triangle is formed when three stones of the same color are arranged at a right angle.” This was one of the only phrases in the book referring to a technical aspect of the game Go. It is known as a bad shape because it reduces efficiency and the chances of not being captured. The general practice was obviously to avoid bad shapes. But I didn’t see it in that way. I believed that an empty triangle itself was inefficient, but could be the lifesaver depending on how the stones were laid out on the Go board.

That day, experts on Go spoke about the “beginning of the Korean approach”. It meant that Korean Go started to take its own course, breaking away from the standards established by the Japanese Go. Ever since that round, Korean Go did grow and prosper by breaking one by one the rules and the taboos defined by the players in Japan.

Cho notes that Go was about training oneself for self-discovery and enlightenment, and observing code of behavior and courtesy for good play. Then, the Korean Go came along, challenging to put all patterns and courtesies aside. Since then, Go began to be perceived as a competitive brain sport. A strong instinct for survival and the thirst for victory engendered an inventive way of thinking.

The Go Magic Course “Go Shapes Level 1” in lecture “Empty Triangle Is Not Always the Bad Guy” (watch it free on youtube) features a pro game where the empty triangle was an exquisite move. Not surprisingly it was from another of Cho Hunhyun’s games, this time versus Zhou Heyang.

Conclusion

Cho Hunhyun’s autobiography transcends the genre of a sports memoir to become a timeless lesson in mental discipline and intellectual courage. Through his journey, we learn that mastery is not the product of flawless technique alone, but of a character tempered in solitude and resilience, one that learns to trust its own intuition above convention. His life—from the harsh lessons of Master Segoe to the historic Ing Cup victory and his controversial advocacy for Go’s evolution—demonstrates a relentless commitment to the game’s spirit, even at the cost of its traditions. Cho teaches us that to “go with the flow” is not to be passive, but to engage so fully with the present moment that calculation becomes instinct, and pressure reveals genius. He leaves us with a powerful legacy: that the most profound moves, in Go and in life, are not found in textbooks, but are born from a mind unafraid to see the board anew.

Leave a comment