Is That a Thing? An Interview with Seasoned Go Players on Hikaru no Go Scenarios

Alexander Dinerstein 3p and Nathan Harwit 6d share their perspectives on the whacky world of HnG scenes and situations.

As a relatively new entrant into the world of Go back during the pandemic, the animated TV series Hikaru no Go (HnG) provided one of the few opportunities to learn about Go culture in non-English speaking countries where it is most popular like Japan.

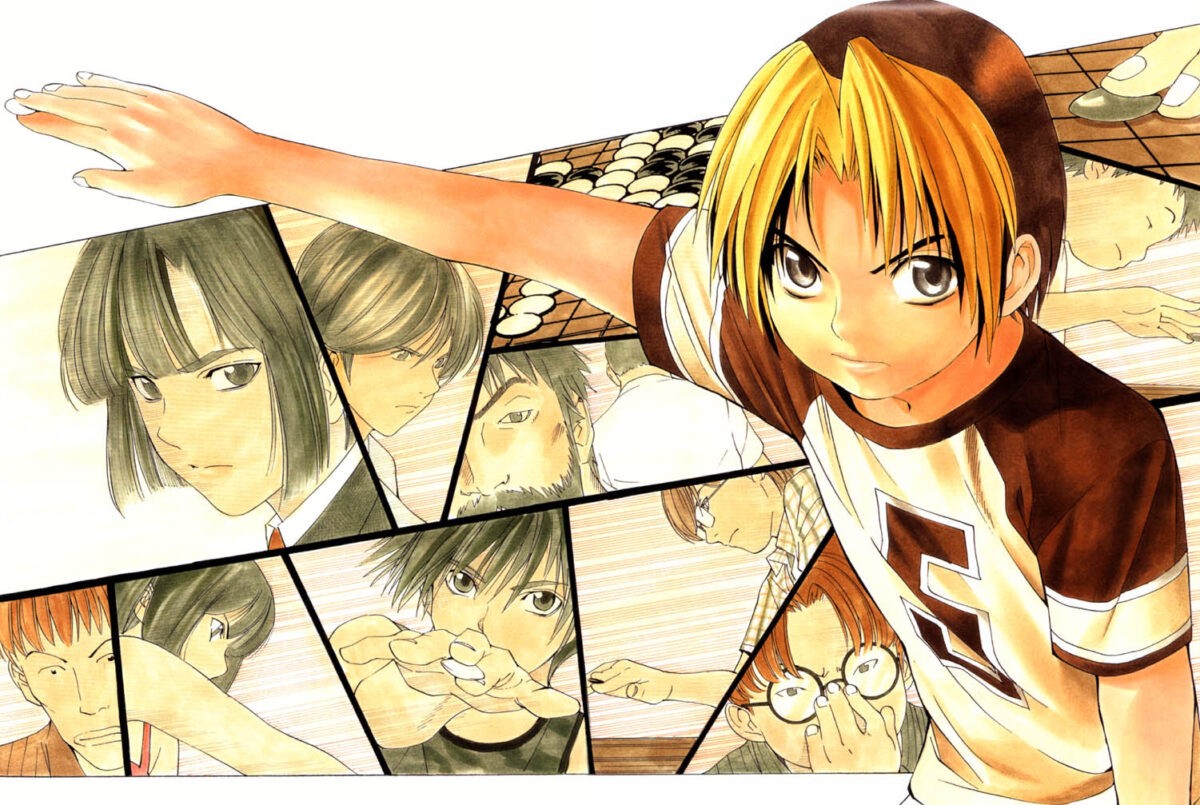

If you haven’t seen it, the 90’s-era show dramatically follows Japanese Go-playing teens who strive to become professional while also dealing with Go spirits of the past and intense rivalries. Scenes depict epic moments of stones being hurled onto a Go board as though going into hyperdrive. After finishing, I had some questions about specific events throughout the series. Do these situations really happen in real life or are they just far-fetched exaggerations created for entertainment value?

I posed some of these questions to players who have devoted significant amounts of their lives to the game and who can provide relevant insights from different backgrounds and cultures: Nathan Harwit and Alexander Dinerstein. Nathan is a 6-dan amateur who has spent years teaching all ages and experience levels the game and who has also worked with Go clubs and organizers across the United States. Alexander has been playing Go since 1986, is a 3-dan professional by training, and studied in South Korea before becoming a teacher of the game and author of many books and articles.

Before We Begin

Nathan, how did you first learn about Go and what was your path going from beginner to 6-dan amateur like?

I started learning Go 15 years ago when I was 9 years old. My twin and I were at a Chess tournament taking a break when we stumbled upon a kid playing Go. We asked him about the game and he said he learned from the Boulder Public Library Kids and Teens Go Club. We started teaching at the Go club in 2009 / 2010 when we reached Dan level, and taught there for the next 12 years. It took about 1 year to reach 5 kyu, and 2 more years to reach 1 dan. It was another year to reach 3 dan and 7–10 more years to reach 6 dan, where I am now. I currently teach 12 students full-time online, which I acquired from a reddit post on r/baduk. I’ve been teaching online for a year now, and it’s still extremely fun and exciting!

Alexander, what was your path like to becoming a Go professional?

I learned to play Go from my father, who was a 10-kyu player, when I was 6 years old. Then I came to Valery Shikshin’s School and successfully reached 5 dan. From 1997 to 2002, I spent five years in Korea, studying in various clubs with future world champions like Park Yeonghun, Kim Jiseok, and Kang Dongyun. After obtaining my first professional dan, I worked in an adult Go club where I witnessed the ins and outs of playing for money (but did not play high-stakes games myself). Then I returned home and have been actively promoting Go all these years.

Scene 1

In the beginning of the show, we learn the backstory of Fujiwara No Sai, the ancient Go spirit that inhabits Hikaru’s mind. When retelling key events of Sai’s life, he discusses how he lost his livelihood as a professional Go player when Sai’s opponent cheated and placed a stone of Sai’s color into his own pile of prisoners, thus gaining a small lead. Does this happen?

Alexander: There was an incident at one of the World Go Championships where Korean and Chinese representatives played a game. The Chinese player returned one of his captured stones back to his bowl as a force of habit since Chinese rules do not incorporate captured stones into the final score. Because the game was played by Japanese rules, however, where captured stones matter, the Chinese player won by half a point. The Korean player protested, saying that he had been estimating the score thinking that this captured stone wasn’t there, and then it suddenly appeared at the end of the game. Believe it or not, but they were forced to replay the game.

I personally experienced a sad episode similar to this HnG scene at a Korean Go club where I studied in 1997. Many kids who studied there later became top professionals, and during one practice game I saw my opponent was holding something under the table. I asked him to open his hand, and, sure enough, there were several stones. Similar to this part of the show, he was planning to add the captured ones to gain an unfair advantage. He quit Go after this in disgrace and I never heard his name again. It was a real shame; he was really talented and had the potential to become another top 9 dan.

Nathan: I haven’t seen this happen (at least in the US) for a few possible reasons: Lots of people play online, so it can’t really happen there. For live games, most people play at Go clubs where they know each other. Also, without money on the line at these clubs, there is no incentive to cheat. I could see this possibly happening in a tournament, but it would be hard to prove that the opponent stole a prisoner.

In your opinion, does the temptation to cheat given the proliferation of AI programs and their ease of access make it a bigger problem today than in the past?

Nathan: Yes, there’s a lot of cheating nowadays because anyone can download Katago, Leela zero, or other strong AI programs. There was a little girl who was a child prodigy and got caught cheating using AI. She started playing on the Fox Go server again and is still scary strong. She often makes it very far in big tournaments. It’s sad to see how she resorted to cheating when she’s already so strong. The Fox Go server has arguably the most cheating simply because it has the most players of any Go server.

Alexander: Yes, it is becoming a bigger problem these days. Nathan’s example reminds me of the case of Kim Eunji. She had just recently won her first professional dan rank and was one of the promising young Korean players until she was caught red-handed when cheating in an online tournament game against Lee Yeongkyu 9 dan. She was using an online AI web service called Katago and the website creator later confirmed that she used the AI program during this game and was therefore disqualified for a year and suspended from both online and offline tournaments.

Another young Korean pro, Do Eungyo, was using the help of AI in a casual online game. When her Chinese opponent later analyzed the game, she discovered that Do had been cheating and published a post about it on a Chinese Go forum. This story made it to the Korean Go federation and she confessed that she had cheated using AI and was also disqualified for a year.

Scene 2

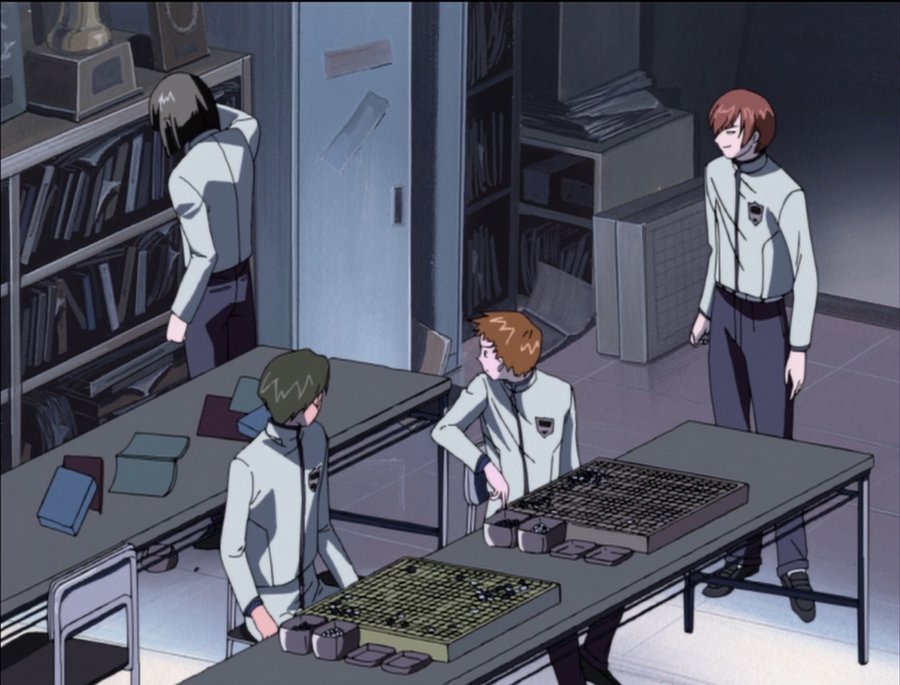

Early in the show, Akira Toya, one of the main characters and an incredibly talented young player, plays simultaneous games “blind” against two schoolboys with his back facing the boards. Have you seen this done in real life?

Alexander: There is a Chinese 7 dan amateur player named Bao Yun, who is quite strong and set a Guinness world record by playing 5 blind games simultaneously. Our Russian master Timur Sankin was one of the participants and recalled that he was playing his best but resigned after getting into a hopeless position and not wanting to torture his blindfolded opponent with endgame moves. He says he lost that game fair and square. I haven’t tried playing blind Go myself. I think one has to have a unique memory for that.

What’s interesting is that many chess players can do this, and it is believed that even an intermediate player with a rating around 2000 should be able to play a blind game.

Speaking of “blind” Go, there is a world Go championship for the visually impaired held in Japan. Most participants are Japanese but they do have the official status of a world championship. They play on special boards on which stones sit on protruding board lines, and black and white stones have different textures. This is, of course, easier than playing from memory without a board since you can feel around to check stone positions.

Nathan: I remember at a Go Congress about 5–10 years ago I watched a 7 or 8-dan AGA (American Go Association) actually play blindfolded facing the board and did it simultaneously with multiple games at once. He was extremely good at it and was only slightly weaker than his normal rank when playing out the whole game like this. This seems extremely hard for most people to do though. I likely couldn’t get past 30 moves, although I’ve never tried. This is similar to one color Go, which is likely much harder.

Scene 3

Later in the show, Hikaru plays an up-and-coming professional Go player. To prove his abilities, they play a game where each side plays only using white stones, called “one color” Go. How difficult is this variation on Go and is it played on the honor system?

Nathan: Similar to playing simultaneous games blind, “one color” Go is challenging, but possible; some people are good at it. I don’t see it played often, but it does help with one’s reading and visualization abilities. I used to play one color Go with my twin on the 9-by-9 board. What typically happens is one side loses track of which stones are which and is then basically forced to resign.

Whenever I or someone else at the Go club play “one color” go, it’s on the honor system. You could have a third person watch and keep track on a separate board or computer. That would be pretty interesting, although it may not be too helpful when compared to just playing games or doing tsumego, I think it’s a fun experience to try at least once. I recommend playing on the 9-by-9 or 13-by-13 board once you have the basics down (~20 kyu).

Scene 4

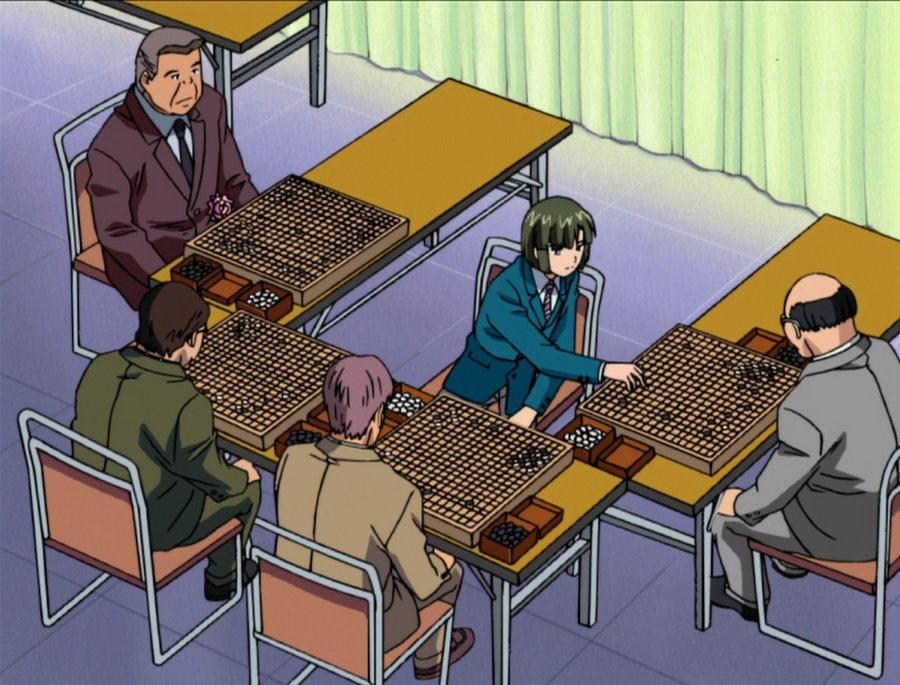

Multiple characters in the show play simultaneous games where they aim to achieve a tie in all the games. Is this done or even possible in your experience?

Alexander: It’s a special kind of skill to create the necessary game result. There is a tradition in Korea that some VIPs, including sponsors of large tournaments, play exhibition games with professionals. Those games would be played with a 4-or-5-stone-handicap and close results are very common. Some pros create a tie or lose by one point. When reviewing the end game moves, however, a trained eye can tell that the pro was doing it intentionally. Intentionally creating a tie without anyone realizing it (your opponent included) is quite hard. There is nothing shameful in doing this though. It’s more important that the sponsor is satisfied and keeps sponsoring other tournaments.

In the old days there was a famous Oteai tournament in Japan that was used to achieve dan-level promotion where players would receive some money for each game played. A pair of players exploited this rule by tying their games several times in a row to get paid more. This led to the payment rule being promptly revoked.

Nathan: This is possible, although to tie, there would have to be no komi (or no half-point komi). Also, the difference in rank between players matters a lot; if the stronger player is not much stronger than the opponent, it will be very hard to keep the game close enough to actually tie. And, yes, it becomes difficult not to make it obvious that you are trying to tie. You would have to gauge how your opponent will play the rest of the game and constantly reassess so that you can predict where they will lose points and thus give you a tie at the end. Because of this, you have to be extremely good at counting to make this work.

Scene 5

In a Go salon, a fellow student of Hikaru named Yuki cheats when counting points at the end of the game by moving black and white stones with his fingers on different parts of the borders between territories. Yuki also taps on the side of the board when playing another student in one scene to trick the opponent into illegally playing twice in a row and therefore lose the game. Do you ever see these forms of cheating happen?

Nathan: Moving borders is possible, although I’ve only ever seen it when teaching kids under 12 years old. It doesn’t usually work because I know what the ending score should be, and I also watch the board when we are counting. If I think I should have won by 5 points but then lose by 5 points, something is probably fishy. Tapping on the side of the board is usually done as a joke. No one actually forfeits the match if they accidentally play twice. In higher level tournament games, it would be obvious if your opponent hasn’t moved yet. Either way, I’ve never seen anyone actually try this as a trick to try to win the game.

Alexander: There has never been any incidents of cheating during counting in professional Go as far as I can remember. In Korean Go clubs, however, it happens. I lived at a club owner’s home for about a year and saw many of those things firsthand. For those who want to know what it looks like, I recommend watching The Stone or The Divine Move. The former feels very much like a documentary film, and it captures the atmosphere of Korean Go clubs very well. The novel First Kyu also explains nicely how Koreans gamble when playing Go.

To give you an idea, players first set the amount for winning by 10 points — called 1 ban — and the amount of money for the largest loss — called manban, or 100 points or more — and this money is placed under the goban or board. A normal stake at the time was $10 for 1 ban, and therefore $100 for manban, however, I’ve seen games with much larger stakes. I’ve witnessed, for example, Korean apartments being lost in these games, little by little over several days. The player who lost money would often come back to the club afterward and — not having any more money with which to wager bets — watch who they lost to closely just to know the future fate of their lost money.

Scene 6

In Hikaru’s first professional game against Toya Meijin, reverse komi is used as a handicap. Is this common practice? What is the effect of using reverse komi versus putting extra stones down as a handicap?

Alexander: Reverse komi is mostly used in friendly games, not in tournament matches. As far as I know, young Japanese pros today play their first game as pros with a two-stone handicap against a seasoned pro. I don’t prefer reverse komi because it can inadvertently teach a student to play more passively. My personal preference is a type of three-stone handicap called a Chinese handicap. In this starting board setup, there is one corner to trick your opponent with joseki and there are three black stones that are not necessarily placed on star points.

Nathan: Using reverse komi is common. In the Next Generation Exhibition Match in December 2021, the games were all reverse komi. I think this is done to show that players were fairly-evenly matched and also because the games are more realistic without handicap stones. [To Alexander’s point] Reverse komi does change the game dynamic a little. You can modify your style of play to improve your odds of winning with reverse komi versus, for example, a two-stone handicap. This is because you now get a small amount of immediate territory with reverse komi instead of needing to convert two stones into more territory than your opponent. Therefore, with reverse komi, you can play much more defensively and just play for territory. This depends on the amount of reverse komi given, of course. Consider this: if a nine-stone handicap is worth about 100 points (each handicap stone is worth around 8–12 points depending on how many there are), do you think your odds of winning would be better if you gave your opponent 100 prisoners to start the game (reverse komi) or if you gave them nine stones as a head start (handicap) where they need to convert their stones into territory?

Scene 7

During the insei pro exam, Hikaru plays a student who puts down a stone and then quickly moves it, which is technically illegal. Does this happen often?

Nathan: I don’t see this much in America, but if it’s a friendly game at a Go club and it’s not done with malicious intent, most players just let it go. In a tournament, most players would be upset and likely involve the tournament director to settle the dispute.

Alexander: Playing two moves in a row, moving a stone after it touches the board…all of these situations are illegal in Asian Go rules and are punished by an immediate loss. This does happen from time to time in professional matches in Asia, however, European rules are a lot less strict. One can, for example, place a stone on the board and then — without letting it go — put it back in the bowl and keep thinking about the move. Or place a stone anywhere on the board and then slide it to the desired position. Neither playing twice in a row or taking a ko by mistake without playing a ko threat first lead to a loss.

Scene 8

Akira plays a student who simply mirrors Akira’s moves by playing “copycat” moves. Do you come across this? If so, where?

Alexander: In the history of professional Go there was a famous master, Fujisawa Hosai, who used this “mirror” Go strategy playing white in almost every game. He even managed to beat Go Seigen with this. His strategy was to take less territory for himself and give more to the opponent. This would then allow the chance to play a move in the center to enlarge his moyo, or framework, first and then play an invasion and live inside since it’s easier to live in a larger area. It was his signature strategy, and other masters tried to come up with ways to counter it knowing that he would use it against them. Kajiwara Takeo, for example, played a first move in tengen [the center point on the board], perhaps the only time in his professional career, simply to not allow his opponent to mirror his moves.

Among European masters today Jonas Welticke is known for using this strategy too. I even lost a game to him once like that. I tried to counter it by creating two ladders that run into each other but it turned out that it doesn’t always work that well. It’s possible to interrupt the mirroring at the right point and get a decent result, but I have to say it was quite an unpleasant experience. I have never tried using this strategy myself.

Nathan: Sometimes you’ll see this online, or when people are trying to beat the AI with the strategy. It’s not great manners to do this though, and most people frown upon this strategy. It doesn’t work because you can simply play tengen and the symmetry breaks. I think they showed this happen in the actual scene.

Great article! Very interesting real life stories that you guys provide

Very interesting article.

I could not find any more information about the film “The Stone or The Divine Move”. Does it maybe have another title?

I just recently watched through HnG again, so seeing these situations come up, it was fun to see what a couple professionals thought. I’m not experienced enough to know what situations would be possible, so it was cool to see that a lot of things can actually happen.

Extremely interesting article. I didn’t even remember HnG having so many different types of Go-related situations.