Lee Sedol vs. AlphaGo What Really Happened in the Match

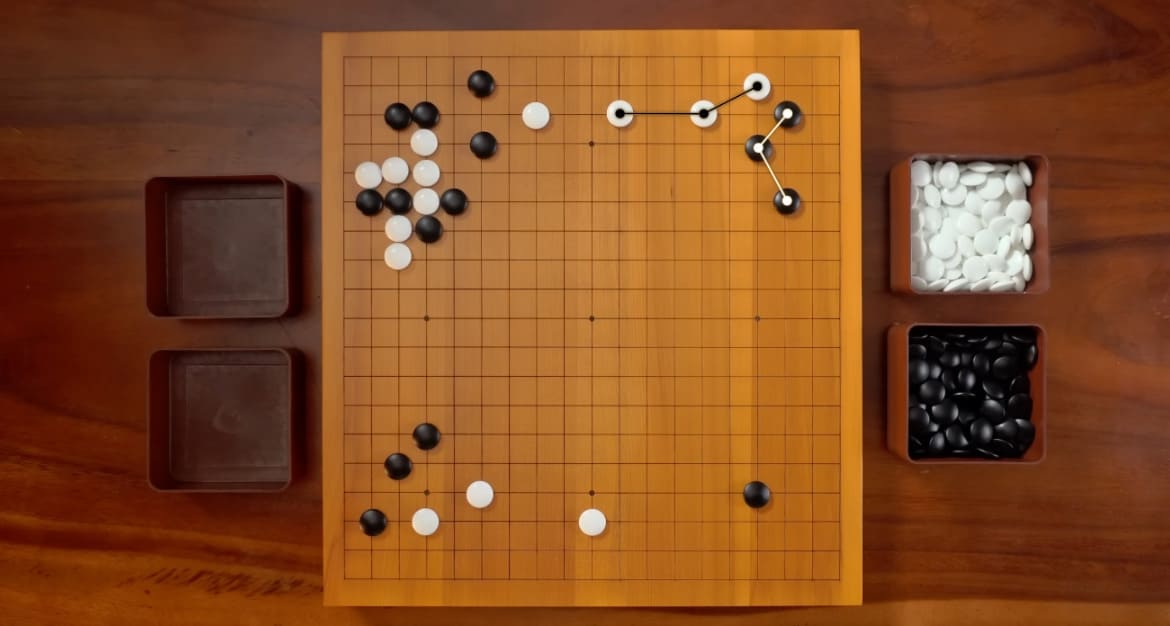

For decades, Go stood apart from other games where machines eventually surpassed humans. Its depth, intuition, and resistance to brute-force calculation made it feel uniquely human.

That confidence began to crack in 2015, when DeepMind introduced AlphaGo — a system that did not merely calculate, but learned.

Within months, it defeated a professional player, and by March 2016 it faced Lee Sedol, one of the greatest Go players of his generation, in a match that reshaped how the game itself was understood.

This article revisits that story from a Go player’s perspective, focusing not on code or algorithms, but on moments, decisions, and consequences.

This article is adapted from a video on our YouTube channel.

More Than a Match: Why AlphaGo Became a Story

At first glance, the AlphaGo matches look like just another chapter in a familiar narrative: computers eventually defeat humans at yet another game. That script had already played out before. Checkers fell in the 1990s. Chess followed soon after. By the time AlphaGo appeared, many assumed Go would simply be next on the list.

But Go resisted that fate for decades, and when it finally happened, it did not feel like a routine handover of supremacy. The AlphaGo matches became a story not because a machine won, but because of how it won, and what that revealed along the way.

From a Go player’s perspective, the significance was never only about the final scores. It was about intuition being challenged, long-held ideas about “good shape” and “proper play” quietly collapsing, and the uncomfortable realization that creativity was no longer a uniquely human refuge. The games forced players to re-examine habits that had felt almost timeless.

This is why the AlphaGo story cannot be reduced to diagrams and move numbers alone. It unfolded as a narrative: skepticism, disbelief, gradual recognition, and finally, acceptance. Long before people spoke about neural networks and training pipelines, Go players were already sensing that something fundamental had shifted on the board.

What AlphaGo Was — and Why Few Expected a Miracle

AlphaGo was developed by DeepMind, a research company operating under Google. Yet in its early days, that pedigree alone did not inspire much fear among professional Go players. Programs had been improving steadily for years, but they still lagged far behind top humans, and experience suggested that AlphaGo would follow the same trajectory.

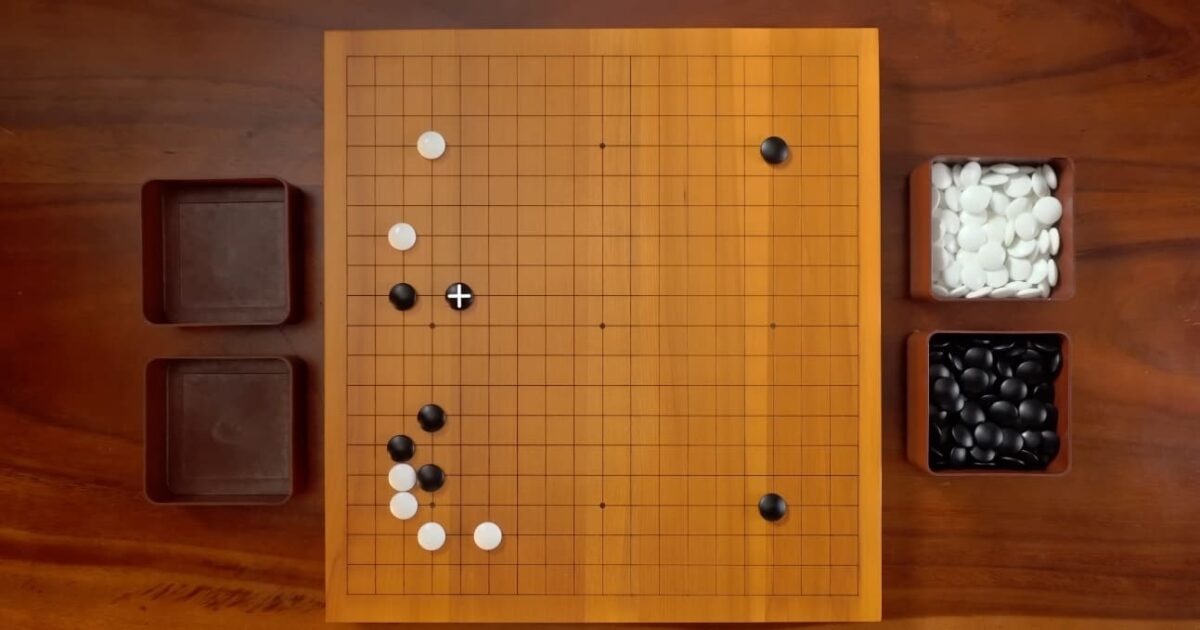

At a high level, the system was built in a way that even non-technical observers could grasp. It began with a large database of human Go games, used as training material rather than rigid instruction. Several neural networks worked together. One of them learned to scan positions, recognize recurring patterns, and predict likely next moves. Its predictions were far from perfect — not absolute truth, but something closer to educated guesses. Accurate enough to be useful, yet nowhere near infallible.

Alongside this, another network was trained on finished games. It was shown positions and told who eventually won from there. Over time, it learned to estimate which side was ahead in any given position. Again, this evaluation was imprecise. Early accuracy was modest, sometimes closer to sixty percent than certainty. But it did not need to be perfect. It only needed to be good enough to guide the next step.

That step was self-play.

Armed with these rough predictive tools, AlphaGo began playing vast numbers of games against itself. Each game produced new data. Each outcome fed back into the system, refining its sense of which decisions led to success and which did not. Patterns were generalized, assumptions adjusted, and the entire cycle repeated again and again. This process — reinforcement learning — is where AlphaGo’s real strength began to emerge, slowly and quietly, beyond anything a static database could provide.

It is worth emphasizing how provisional all of this still was. By the creators’ own admission, this description glosses over countless technical details. It is a deliberate oversimplification — a way of sketching the idea without drowning in mathematics. Those who know the field more deeply would no doubt find gaps and shortcuts in the explanation, and the invitation to point them out has always been open.

What matters for the story, however, is how AlphaGo looked at that stage. It was not yet the cold, merciless engine people would later imagine. Its play often appeared recognizably human. It followed established openings, made conservative choices, and sometimes missed opportunities that modern AI tools now identify immediately. Even its creators described it as a work in progress rather than a finished weapon.

That context explains why expectations remained modest. Go players had seen promising programs before, only to dismantle them with relative ease. AlphaGo, at least on paper, seemed like another incremental improvement — impressive, perhaps, but not revolutionary.

What followed would prove just how misleading that assumption was.

The Fan Hui Match: The First Crack in Human Confidence

Before the world turned its eyes to Seoul, AlphaGo had already faced a professional opponent. In October 2015, DeepMind arranged a quiet, almost low-profile match against Fan Hui, a Chinese-born professional Go player living in France and a three-time European champion.

On paper, Fan Hui was a sensible choice. He was unquestionably strong, experienced, and fully professional, yet not surrounded by the near-mythical aura reserved for the absolute elite of East Asian Go. When the invitation arrived, skepticism came naturally. Programs had challenged professionals before, and the results were rarely alarming. Fan Hui agreed to play, likely expecting a competitive but manageable encounter.

That expectation dissolved quickly.

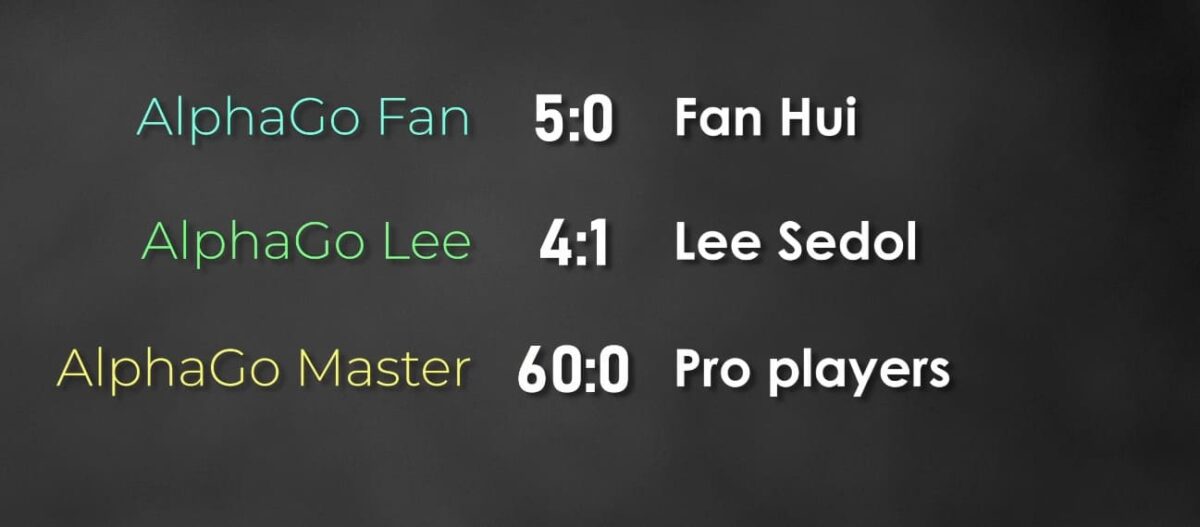

Game after game, AlphaGo won. Not narrowly, not by exploiting a single oversight, but convincingly. The match ended 5–0 in favor of the machine — the first time a professional Go player had been completely swept by an AI in an even match.

And yet, the shockwaves were strangely muted.

Within the Go community, the result sparked whispers rather than panic. Some questioned Fan Hui’s true strength. Others suggested that living and competing primarily in Europe had dulled his edge compared to Asian professionals. There was sympathy, too — losing five consecutive games to a machine placed an immense psychological burden on any player.

Most importantly, many players simply did not interpret the match as definitive. AlphaGo had won, yes, but perhaps not meaningfully. The prevailing belief remained intact: against the very best humans, this machine would surely falter.

In hindsight, this moment reads as the calm before the storm — the point where the warning signs were visible, yet comfortably ignored.

A Human-Like Machine: Early AlphaGo’s Limits and Mistakes

Part of the reason AlphaGo’s victory over Fan Hui failed to trigger alarm was the nature of its play. This early version of the system did not resemble the relentless, inhuman force later associated with AI Go.

Its openings looked familiar. Established joseki appeared on the board. Defensive shapes that had been standard for decades were played without hesitation. In several positions, AlphaGo chose solid, conservative extensions that modern AI tools now consider inefficient or unnecessary. To an experienced observer, much of the game felt comfortably recognizable.

More strikingly, AlphaGo made mistakes.

From today’s perspective, with far stronger analysis engines available, some of its decisions are clearly suboptimal. There were missed exchanges, ignored urgent points, and moments where a sharper move could have shifted the balance more decisively. In certain games, modern AI analysis even suggests that Fan Hui’s play surpassed AlphaGo’s in parts of the middlegame.

This was not yet the era of ruthless precision. AlphaGo’s style mirrored human caution. It preferred secure paths to victory over maximal gains, sometimes settling for safe territory instead of pressing harder advantages. That tendency would later be understood as a defining trait rather than a flaw, but at the time it reinforced a comforting illusion: the machine was strong, but still human-like, still imperfect.

Seen through that lens, the 5–0 scoreline felt less like a prophecy and more like an anomaly. The Go world had not yet grasped that this was only an intermediate form — a system still learning how far beyond human habits it could go.

The real test, many believed, had yet to begin.

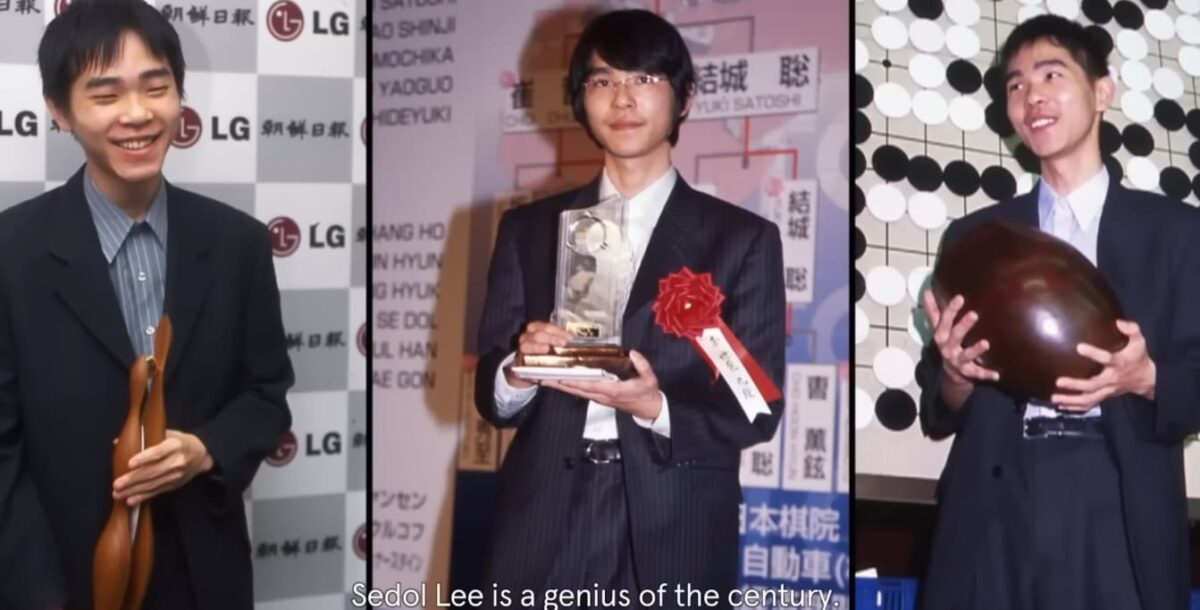

Lee Sedol Before the Match: Confidence of a Legend

When DeepMind announced that AlphaGo’s next opponent would be Lee Sedol, the context changed instantly. This was no longer a quiet test against a strong professional. It was a public confrontation with one of the defining figures of modern Go.

By 2016, Lee Sedol’s reputation was firmly established. A multiple-time world champion, known for his fighting spirit and creative problem-solving, he embodied a distinctly human ideal of Go mastery. Where some players were admired for stability and efficiency, Lee was feared for his ability to complicate positions, find unexpected resources, and turn chaos into opportunity. Against human opponents, that style had won him countless titles.

Naturally, Lee reviewed the games AlphaGo had played against Fan Hui. What he saw did not disturb him. The machine appeared strong, but not overwhelming. Its play still carried visible inaccuracies. Some choices looked conservative, even timid. From Lee Sedol’s perspective, the conclusion seemed obvious: AlphaGo had beaten a professional, but not this professional.

Publicly, he expressed confidence. Privately, the only uncertainty he admitted concerned the final score. Would the match end 5–0 or 4–1 in his favor? The idea that AlphaGo might dominate him outright did not seriously enter the conversation.

What Lee — and everyone else — could not see was what had happened in the months between October 2015 and March 2016. During that time, AlphaGo was trained relentlessly. Millions upon millions of self-play games refined its judgment, reduced its weaknesses, and reshaped its understanding of the board. No external observer had access to those results. The machine that would sit down in Seoul was not the same one that had played Fan Hui.

That asymmetry of knowledge mattered. Lee Sedol would discover AlphaGo’s true strength only when the first stones were placed on the board. Until then, confidence filled the gap left by uncertainty — a confidence shared by most of the Go world.

The stage was set for a reckoning that few expected to unfold the way it did.

Seoul, Game One: When the Plan Failed Immediately

By the time the match began in March 2016, anticipation had reached well beyond the Go community. The games were broadcast live, commentary ran in multiple languages, and public viewing events filled halls and city squares in Seoul. This was no longer just a professional match. It had become a cultural moment, framed as a test of human intuition against machine calculation.

The opening game began quietly enough. Lee Sedol settled into a relaxed rhythm, playing with the confidence of someone who believed he understood the balance of power. Early positions seemed favorable. Black had solid points, White appeared light and scattered, and commentators described the game as comfortable for the human side.

Then AlphaGo did something unexpected.

Instead of avoiding complications, it initiated an early fight. It cut, peeped, and separated stones in a way that forced Lee Sedol to juggle multiple weak groups at once. The board grew tense almost immediately. Rather than steering toward calm territory, the machine pushed the game into instability — precisely the kind of position where human creativity was supposed to shine.

From the commentary desk, reassurance continued. The situation looked complex, but manageable. Lee Sedol, after all, was known for thriving in chaos. Yet as the middlegame unfolded, a subtle shift became visible. AlphaGo was not merely surviving the complications; it was controlling them. Each local skirmish resolved just slightly in its favor, and the cumulative effect began to tell.

Modern AI analysis would later confirm what few recognized in real time: from very early on, the game had been comfortable for White. The apparent balance was misleading. AlphaGo’s advantage, small at first, widened steadily after the initial fight.

By the time the endgame arrived, the outcome was no longer in doubt. AlphaGo secured the win with calm efficiency, making conservative choices that prioritized certainty over spectacle. The final margin was modest, but the psychological impact was anything but.

For the first time, Lee Sedol faced a position he could not reverse. The loss itself was surprising. The manner of the loss was unsettling. AlphaGo had not won by brute force or by exploiting a single oversight. It had dictated the character of the game from the opening onward.

The match had barely begun, and already the original assumptions were under strain.

The Realization: AlphaGo Was Playing Creatively

If the first game unsettled expectations, the second game dismantled them.

At the start, nothing seemed out of the ordinary. The opening developed smoothly, positions remained balanced, and Lee Sedol followed a familiar plan, building influence while keeping options flexible. There was no immediate sense of danger, no obvious misstep. Then AlphaGo played a move that froze the room.

It was not just unexpected. It looked wrong.

A shoulder hit on the fifth line violated basic Go instincts. Such a move is traditionally used to press an opponent’s stones downward, reducing their influence. Here, it appeared to do the opposite — seemingly granting territory instead of limiting it. Commentators hesitated. Spectators stared. Even experienced professionals struggled to explain what they were seeing.

And yet, the move worked.

Slowly, its purpose revealed itself. The stone did not aim for immediate profit. Instead, it connected distant parts of the board, supported multiple weak groups at once, and quietly prepared future attacks. What initially looked like a concession unfolded into a position of remarkable harmony. AlphaGo had not followed human convention, but it had followed logic — a logic that transcended established patterns.

This was the moment when the narrative shifted.

Up to that point, it had been possible to believe that AlphaGo was simply an extremely fast and disciplined imitator, recombining ideas learned from human games. That explanation collapsed here. No professional would have chosen this move. No textbook suggested it. And yet, the machine had found it independently and trusted it enough to play it on the world stage.

After the game, Lee Sedol himself acknowledged the significance. This was not a system blindly searching through a database. It was capable of original ideas. It could evaluate positions in ways humans did not yet understand.

The psychological balance of the match changed irrevocably. AlphaGo won the second game and took a 2–0 lead, but the scoreline told only part of the story. The deeper loss was conceptual. A long-standing belief — that creativity was the final barrier machines could not cross — had just been breached.

From this point forward, the match was no longer about whether AlphaGo could win. It was about whether the human side could find anything the machine had not already seen.

Pressure and Adaptation: When Changing Style Backfires

With a 2–0 deficit, the match entered a dangerous psychological zone. At this level, players are not only fighting the position on the board, but also their own instincts. The temptation to do something different becomes overwhelming.

In the third game, the human strategy shifted visibly. Rather than settling into familiar structures, the opening was steered toward immediate conflict. Stones were attached early, groups were split, and the board filled with unresolved weaknesses on both sides. The intention was clear: force chaos, accelerate the pace, and drag the game away from AlphaGo’s calm, methodical control.

This approach is understandable. Against a system that seems to evaluate everything with quiet precision, the natural response is to create positions where evaluation itself becomes difficult. Fighting Go has long been considered a human stronghold — a domain of intuition, courage, and emotional reading of the opponent.

But experience offers a harsh lesson: changing one’s fundamental style under pressure is rarely effective.

As the game unfolded, AlphaGo handled the complications with unsettling composure. Groups remained light. Connections appeared just in time. Threats were acknowledged, but never overreacted to. Where a human might feel compelled to press an attack or defend preemptively, the machine consistently chose the move that preserved flexibility.

The fighting continued for dozens of moves. No single group died. No dramatic collapse occurred. Instead, AlphaGo emerged from the chaos with what mattered most: a large, stable framework and a clear territorial advantage. The battle had been fierce, but the outcome felt strangely quiet.

Modern analysis would later reinforce an uncomfortable truth. Among all the games in the earlier match against Fan Hui, the one Fan Hui played best was actually the first — before pressure and desperation set in. His accuracy declined as he tried harder to force results. The same pattern repeated here.

By the end of the third game, the score stood at 3–0. The match was effectively decided. For the first time, the Go world faced a conclusion it had not seriously prepared for: a human legend stood on the verge of a clean defeat, not because he lacked skill, but because the opponent did not crack under stress.

What remained was no longer a fight for victory, but a struggle for meaning.

Game Four: The Human Answer

By the fourth game, the outcome of the match was no longer in question. Down 3–0, Lee Sedol could not win the match, only restore balance to the story. What followed was not a strategic reset, but a psychological release. With nothing left to lose, he played freely.

For much of the game, it looked as though AlphaGo would close things out in familiar fashion. The machine built a large sphere of influence at the top of the board, while Lee Sedol efficiently collected points elsewhere, leaving several stones unsettled and trusting his ability to rescue them later. As the middlegame progressed, AlphaGo maintained a lead of roughly ten points — a margin that, at this level, usually signals a calm glide toward victory.

Then came a moment no one in the room could explain.

In a position that appeared sealed, Lee Sedol found a single move that detonated hidden potential across the board. It activated weaknesses that had seemed irrelevant, linked distant threats into a single idea, and forced AlphaGo into unfamiliar territory. The move did not merely threaten a local outcome; it challenged the machine’s entire evaluation of the position.

This was the move later immortalized as Move 78.

From today’s vantage point, armed with vastly stronger AI tools, analysts know something uncomfortable: objectively, the move should not work. Even after it, Black was still winning by a comfortable margin. But that knowledge belongs to the future. On that day, against that version of AlphaGo, the move struck a blind spot.

AlphaGo failed to find the correct response. One inaccurate choice followed another. The machine’s play, previously so assured, became hesitant and inconsistent. Lee Sedol seized the opportunity with precision, converting chaos into clarity and rescuing stones that moments earlier looked doomed.

For the first and only time in the match, AlphaGo lost its grip.

Lee Sedol went on to win the game, and the reaction was extraordinary. He had won many world titles before, yet never had a single victory been celebrated with such intensity. Applause filled the room. Relief, admiration, and something close to defiance rippled through the audience.

The scoreboard still read 3–1. AlphaGo was still dominant. But something vital had been reclaimed. The game proved that even a superhuman system could be surprised — not by brute force, but by an idea no one else could see.

Beyond Lee Sedol: When the Ceiling Disappeared

With the match against Lee Sedol concluded, DeepMind had shown the world something unmistakable: artificial intelligence was now stronger than any human Go player. The long-standing assumption that Go represented a final, human-only frontier had finally collapsed.

But the story did not stop there.

The version of AlphaGo that faced Lee Sedol was already significantly stronger than the one that had defeated Fan Hui just months earlier. This raised an obvious question: what would happen if the system were given even more time to train?

The answer arrived before the year was over.

In December 2016, a mysterious new account appeared on the Tygem Go server. It challenged the strongest players in the world — and defeated all of them. Sixty games. Sixty wins. No explanations at first, only quiet disbelief. Soon it became clear that this was yet another evolution of the same project, later known as AlphaGo Master.

The following year, AlphaGo Master faced China’s strongest player, Ke Jie, in an official match. The result was decisive. Ke Jie never found a foothold. The match ended 3–0. By that point, AlphaGo had reached what could only be described as a superhuman level.

Still, DeepMind did not stop.

AlphaGo Zero and the End of Human Templates

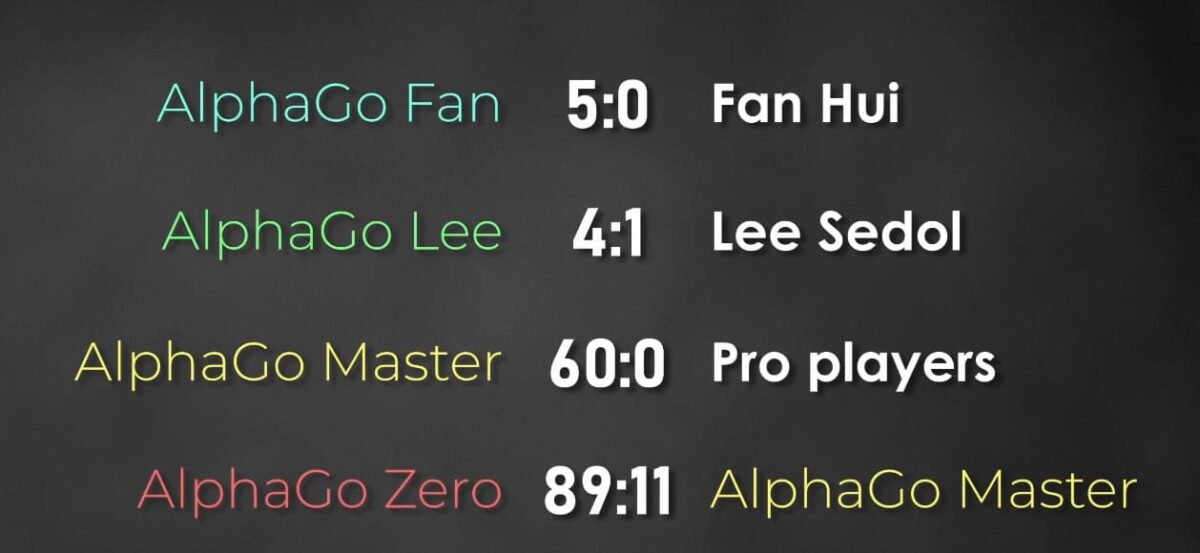

In 2017, a radically different system was introduced: AlphaGo Zero. Unlike all previous versions, it was trained without a single human game. No professional databases. No inherited openings. No conventional wisdom. It learned Go entirely from scratch.

At first, its play was chaotic — almost random. But through relentless self-play, it gradually developed its own understanding of the game. Over time, it surpassed every earlier version of AlphaGo. When tested directly, AlphaGo Zero defeated AlphaGo Master in 89 out of 100 games.

The implication was unsettling. Estimates suggested that AlphaGo Zero was roughly three stones stronger than the version that played Lee Sedol. Had DeepMind waited another year before arranging the Seoul match, the result would not have been dramatic or close. It would likely have been overwhelming.

Once this monumental task was complete, DeepMind published its methods. Other developers were able to replicate the process, and today there are multiple superhuman Go AIs. At that level, distinctions hardly matter. Even freely available tools such as KataGo now play far beyond any human professional.

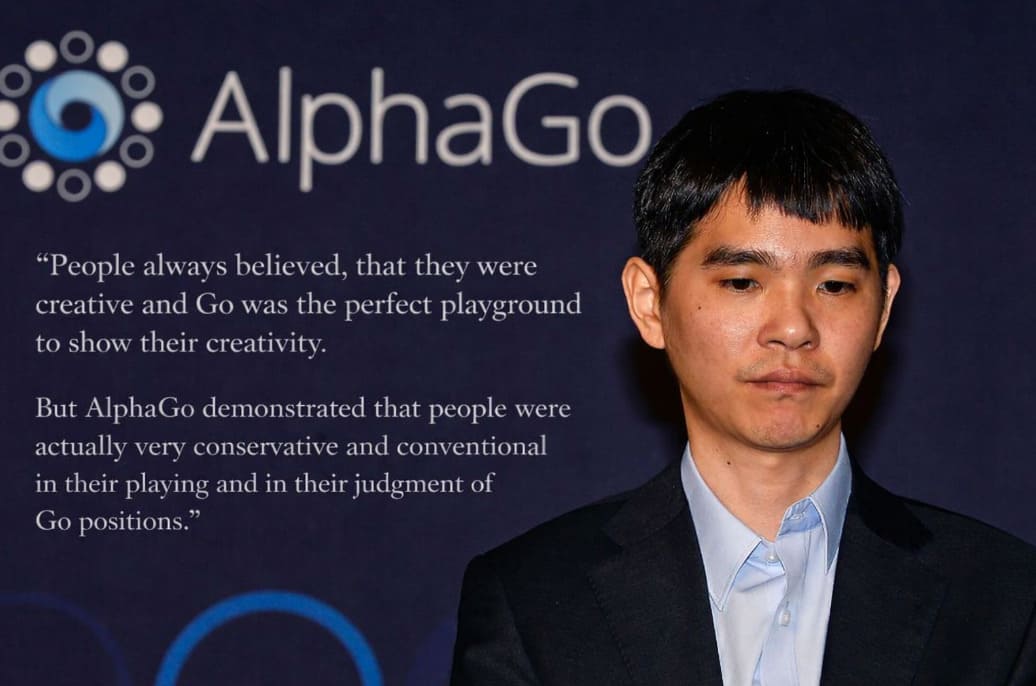

After the match, Lee Sedol reflected on what had happened in a way that struck many Go players deeply. For generations, people believed that Go was the ultimate expression of human creativity. AlphaGo challenged that belief. It revealed how conservative and conventional human play had become, shaped by habits passed from teacher to student, reinforced by tradition rather than exploration.

Ironically, with AI now serving as the benchmark of perfection, players risk becoming just as rigid again — only with a different set of “correct” moves.

What AlphaGo ultimately changed was not just opening theory, though that transformation was irreversible. Ideas that looked shocking in 2017 are now standard practice less than a decade later. The deeper change lies in perspective. Go became larger than its traditions, and creativity was no longer defined by human intuition alone.

The scale of this shift is so vast that it cannot be contained in a single article. Its consequences are still unfolding, and they deserve careful examination on their own.

For now, the board remains. The stones remain. And the challenge remains the same as ever: to create something meaningful, even when perfection is no longer human.

Leave a comment