Reading Is Power: Improving Your Reading Ability in the Game of Go

Reading is the term Go players use for planning one or more moves ahead while deciding where to play next. In other games, other names such as “calculation” may be used, but the process is the same in all games: you try to think ahead, think how your opponent responds to one or more of your moves, and use this to decide where to play. Some players will even say that reading is the single most important skill in Go, so then there should be no doubt it is a worthwhile ability to work on to improve your game. If you can read even one or two moves further ahead than the opponent, it could lead to some crushing victories. So, let’s explore how we can improve our reading in Go!

Did You See the Ko?

Before we begin, I want to tell you about a weekend tournament game I played at the EGC 2024 in Toulouse. The game was roughly even, but I was quite low on time and couldn’t count accurately nor judge the endgame quickly. I wrongly went for an all-in type sequence in the fighting, hoping that something worked and hoping to gain back some time in the process. One situation involved laddering a few stones, which I will show below. As you can see in the simplified position, there are two ladders, and despite trying to read them out under time trouble and find ladder breakers that might make them work, I eventually gave up on that idea. Instead, I hoped to gain forcing moves and attack another group. It didn’t work out, and I later resigned, but after the game, my opponent asked if I’d seen the ko, which I also show you below.

I didn’t see the ko in the game, but also, we agreed there was simply no ko threat big enough to win that ko! Among other things, this is one reason I want to improve my reading: to be able to count quickly, read accurately, and make better decisions in time trouble, as well as more generally at all points of the game.

What Does Reading Look Like?

Every so often players looking to improve will ask the question, “What does reading look like?”. What does it look like when you read: what do you see, do you see the stones, the colours, the variations?

Most likely, not every player’s answer is the same, not every player has the same level of visualisation skill. It will be possible for some players to clearly visualise the board or stones, or in certain situations like tsumego, no doubt. On the other hand, reading can be more like mentally placing blurred markers on the board, something to mean this is a black stone and this is a white stone, but without perfectly forming an image of the stones. For example, the situation below there is a tesuji to capture the two black stones. For some players, there may be no clear picture of the stones themselves, only some kind of mental note to say this move was white, this one black and so on.

Now if you can imagine the colours, then that is useful, but if you can’t, then just remembering that each second stone is an alternate colour is enough, especially in forced sequences of ataris like the above. If you are familiar enough with the shape or tactic, this can be sufficient too as a shortcut to reading out the sequence.

How Can I Improve My Reading?

I believe if you ask most strong Go players, you’re likely to get a single answer: practice! Specifically, they will likely tell you to practice tsumego (life and death) or more general Go puzzles, as this will certainly challenge your reading ability and teach you a lot of new tactics that you can use in your games.

Now there is nothing wrong with that advice per se, but if you don’t like tsumego, or if you are already practicing a lot and not seeing the reading improvement you want, then maybe there is something more specific you can do to identify and improve your weak spots. So let’s try to break down further some of the key aspects of reading in Go, and how you might be able to improve each of them in their own way with different exercises.

Visualisation

Naturally, visualisation is a big part of a board game like Go. You can better anticipate your opponent’s moves and intentions the more stones you can imagine clearly on the board. This in turn helps you decide whether you like the outcomes of sequences or whether it is ok to tenuki (play elsewhere), or whether you need to continue reading wider or deeper.

In terms of trying to improve your visualisation skills, there are a number of things you can think of doing. Like any other exercise, repetition will greatly improve your visualisation skills. You can focus specifically on Go, other board games, or just generally trying to get clearer pictures of objects, but for the moment, let’s focus on Go-related visualisation practice as it is of course directly relevant!

If you are just starting out, trying to visualise basic shapes on the board, either while looking away or with your eyes closed, can be useful. When you can do this, you can then try to further imagine not just the stones but the empty space around the stones, as that is important in Go for picturing liberties and captures.

Blindfold Tsumego

Once you can picture some basic shapes and liberties of stones, you can think of doing some ‘blindfold’ tsumego if you want to work on your visualisation skill. These don’t have to be complicated and probably should be much lower difficulty than your usual tsumego level if you are not used to it. Still, the idea will be to

- Stare at the setup of the problem and begin to memorise the shapes.

- Try to get a picture of the stones in your mind and then look away or close your eyes, while still picturing the problem.

- If at any point you lose the image, try to recreate it in your mind if you can, or if not, simply look at the board again until you can repicture it.

- Solve the tsumego without looking at the board.

- Play through as many of the moves as you can in the solution to the end of the variation.

Here are some shorter puzzles to try to picture, and of course if it’s too easy for you, you can always choose your own!

Generally, don’t be too hard on yourself, any practice and small progress is good! If you can solve tsumego easily while looking at them, but find it hard to picture when not looking at it, then this type of practice could be useful for improving visualisation!

One-Colour Go

Another thing that can often happen in Go is that after some amount of reading, you find it hard to remember which stones were on the board, or what colour a stone was in that position. In particular, you might read out part of a sequence and then wonder how many liberties a group has, and then you might need to start reading over again to remember!

In One-Colour Go, both players use the same colour of stones, for example white, and have to remember which stones are theirs! This might sound a bit complicated at first, but if you have been playing Go for a while, you might also surprise yourself at how much you can remember!

Now if you forget which stones are black and which are the real white stones, then one way to remember is to try to replay the sequence where these stones were placed in your mind, to figure out which stone is which colour. This is exactly like reading but focuses more on the colour of the stones. If that’s an issue you have, then this practice might help you improve that aspect!

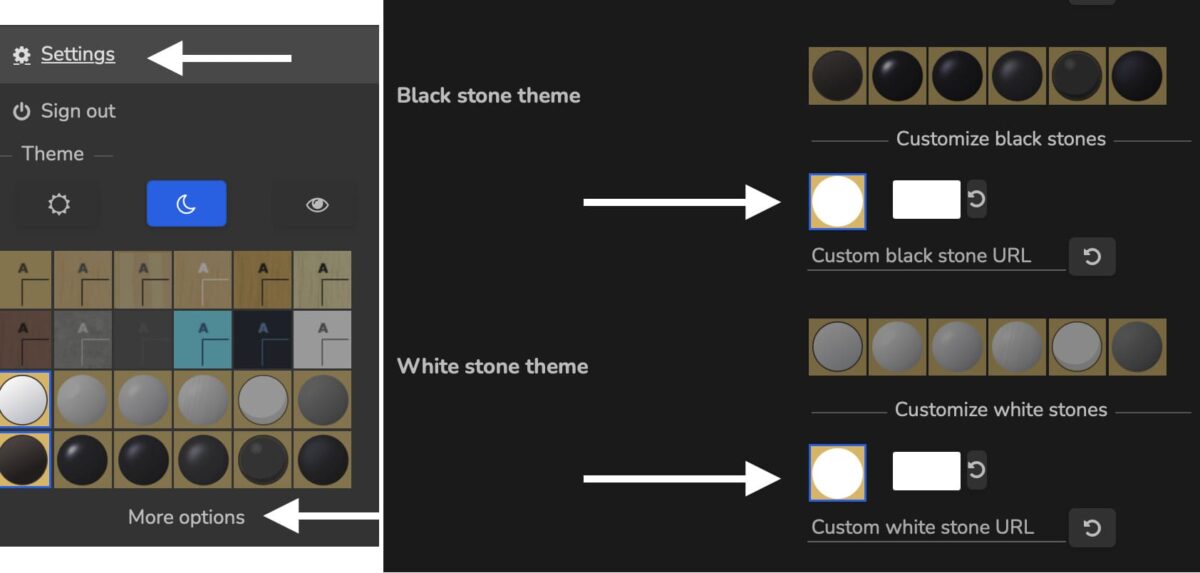

One easy way to play One-colour Go would be to challenge, for example, a computer on OGS to a 9×9 game. You can play an unranked game so you don’t have to worry about winning or losing, and the computer won’t mind if you resign at any point or don’t fully stick to playing with one colour for the whole game, you decide! OGS also allows you to customise the stone colours and even choose both black and white stones to be the same colour. An example of how to do this is shown below:

If you hover over or tap your username/icon in the top right of the screen, there are options to customise stones. If you click “More options”, you will be able to pick custom colours for both stones, or even custom images! Recently, this customisation can be found under settings, and you can change various other settings there also.

Liberty Counting

When reading variations in Go, not only do you need to keep track of what stones have been placed, but you have to keep track of the liberties of each group of stones involved. Many tactics in Go involve a shortage of liberties and being able to identify these while reading is very important.

If you are having trouble keeping track of liberties during games, then you can try a specific set of Go problems called damezumari (ダメヅマリ)or shortage of liberty problems. These problems explicitly require you to visualise and keep track of liberties to capture groups or connect groups as well as living with or killing groups due to a shortage of liberties! Lots of tesuji problems for example involve a shortage of liberties, as stones getting stuck in a net or a loose ladder, can’t escape when they are low on liberties. Similarly, several tsumego techniques rely on a shortage of liberties.

Sometimes you can find books and problem sets dedicated to shortage of liberties problems, and other times you need to look out for them yourself. It is always a good time to start practicing; ask yourself while reading

- How many liberties does this group have?

- After this move, have I increased or decreased a group’s liberties?

- How many moves does it take to capture this group? (sometimes a liberty is more than just the empty space adjacent to the group)

Here are some sample problems to see if you can spot where the shortage of liberties shows up!

Reading shortcuts

When you practice puzzles in your own time you can take as long as you’d like to read out variations, but in a real game, often you have limited time when playing with a clock. So if you can read quickly and accurately this will be to your advantage. Here are some ideas for shortcuts that you can use to your advantage and hopefully it can help you develop your own reading shortcuts also. However, while shortcuts can speed up your reading, a wrong assumption could also potentially lead to disaster. So then the general advice would be: “If in doubt read it out!”

Ladders

Ladders are very common in Go games, but equally they are some of the longer sequences that you might have to read out. In principle they can be fairly simple since every move is an atari, but sometimes as we saw in the “Did you see the ko?” section, they can have some unexpected surprises. Still, there are some reading shortcuts you can apply to ladders:

- Diagonal reading: Once you are familiar with the zig-zag pattern of ladders, then rather than picture each and every stone of both colours, you can sometimes shortcut this by just following a diagonal path of the stones being ladder to see where they end up. You can check if the diagonal line runs into another stone or one space beside another stone or straight to the edge of the board. Practice makes perfect!

- You can also sometimes think of mentally moving potential ladder breaker stones closer to the start of the ladder. For example, a corner star point (hoshi) stone, you can bring diagonally across to tengen (centre star point) and any ladder running into tengen will also run into the hoshi stone. Try it out for yourself!

Does the ladder work for Black here in the first puzzle? In the second puzzle we have moved the star point stone to the tengen point, and kept the same relative positions (knights’ moves) of the nearby black and white stones. Does the ladder work for Black here?

In the previous puzzle, we can also try to use diagonal reading to see if the ladder works. We see that the white stone runs into the black star point stone. However, we do have to be careful to make sure that the nearby white stone doesn’t make any difference to break the ladder near the end.

Move Orders, Vital Points and Key Stones

Sometimes you will find that while reading, two variations lead to the exact same stones on the board, just with different move orders. If you can decide whether this position is good for White or Black, then whenever your reading leads you to this position, you just need to remember who it is good for and stop there. Either you’ll be happy to play this way if your opponent goes down this line, or you or your opponent will avoid this variation, unless someone makes a mistake.

Similarly if you know a particular “vital point” or move that can be played in response to multiple trial moves, like in a tsumego, you can similarly use this as a reading shortcut as with the previous case of move orders. Simply remember if my opponent plays here or here or here … then I always play this move (vital point), and you can stop reading any further, once you are happy with the variation from that point onward. A group might be alive or dead after the vital point is played, or key stones might be captured and so you can shorten your reading in this way.

What are “key stones” you might ask? Even though all Go stones are the same, not all stones on the Go board have the same importance when placed and at all times in the game. If you are reading out a sequence and you can identify which stones you or your opponent cannot afford to lose, this can help you shortcut reading out situations with many options. If your move threatens to capture or even better fully captures some key stones, then you can simply read or play these moves to simplify some variations.

For example in a recent tournament game I was faced with White’s cut at G7.

In this position, I identified G5 and G6 as “key stones”, stones that I can’t afford to lose easily. These are “cutting stones” separating White into three groups, so letting White capture these considerably simplifies the position in White’s favour. So in the following variations, whenever these stones are in atari, I should answer, if White plays F7, I need to think about F6 or E5 to save these stones. Ideas like this can help to cut down on the number of variations you need to consider and give you focus on what sequences to read out and ultimately choose.

As you improve however, you will need to decide which of these “forcing” moves to keep in reserve or which is the best way to capture key stones if there are multiple options. Still, many times the forcing lines will be the easiest to calculate and when they work for you, you can simplify your reading!

Memory and Concentration

You might also find that making a “story” while reading helps you remember the variation or the results of sequences you have read. Some players when reading will assign meanings to moves or use keywords and techniques to help keep track of what is happening. For example, you might see a player reason out a sequence like “I atari, you extend, I block, you hane, I hane …” making a kind of narrative to the sequence to make it easier to understand. Or you might see someone reason “I extend here to gain liberties, then you need to block, then I come back to take away a liberty over here, and this move is a tesuji in this situation…”. These kinds of short stories may help you to reason through more complicated situations and help you to remember sequences you have read, or to quickly help you reread a sequence if you need to double-check it.

In a similar way, you might come across players that have various habits they use while reading. This could be

- making a kind of narrative to work through variations

- a simple finger-wagging or tapping motion, to help mentally step through moves

- a soft sound like “tak tak”, “here, there”, “this, that” and so on, to again help to sort through moves being played mentally.

It’s not necessarily only for reading, but can also be noticed when players are counting or estimating the score on the board. Of course it’s not guaranteed that any player might do this for one particular reason or other, but from my own experience, my feeling is that this can help with concentration. If I am trying to focus on a sequence that I need to read deeply, I might use some technique like this to sort through variations, step through moves and forget other noises around me, from clocks or other players.

You do of course have to be aware of other players in club and tournament situations. If you count like The Count from Sesame Street (one, two, three liberties ah ah ah) or loudly make sounds with stones etc, it can annoy other players.

Once we are aware of some of these ideas, how do we practice and improve?

- For ladders, of course you can try ladder problems!

- Practice tsumego, and the harder the problem, the more you might need to sort through many first moves, and many positions can turn into each other when the best response is played.

- If you want to practice remembering sequences with a “story” like technique, then trying to memorise games, whether smaller 9×9 games or a certain number of moves of your favourite pro games, you should find that making stories and giving meaning to the moves, helps you to remember them better! The meaning can be a reason why you played a move, what you thought your opponent wanted when playing a move or sequence, or just guessing what the pro or strong player might be doing (it doesn’t have to be correct!).

There are other benefits to assigning meaning to moves and memorising games, like being able to remember the first X moves of a game you just played so that you can review it with your opponent or another stronger player or teacher afterward!

Shape memory

If you’ve been playing Go for a while, then you no doubt have heard some players say that “this is the shape move” or “this is the vital point in this shape”. It was mentioned earlier in the context of tsumego, but vital points of shapes apply more generally all over the board. The more you play, the more often you will start to notice certain patterns appearing over and over, in the corners, sides and centre. If you can start to remember special shapes, good and bad shapes, simple tsumego shapes that you have solved, and certain shapes which involve tesuji (tactics), then this can speed up your reading quite a lot.

For example, you might have already heard that some named tsumego shapes are so common you should just know them by heart, like the L-shape in the top left of this diagram. Similarly, you might hear that O14 is the shape point of the four black stones on the right side, so it could be a good move for both players to consider.

If you’re looking to improve your shape memory, when solving tsumego or tesuji puzzles, connection and cutting puzzles, try to picture which stones are the most important to make the variations work. That is, which stones if taken away make the main variations of the solution no longer work. This can help you identify key stones in shapes and ignore stones that serve mostly to clean up the puzzle (You can focus on these in another kind of exercise!). If you haven’t studied “shape” before, then you can do puzzles, read books or articles and watch video lectures about “good” and “bad” shapes in Go in order to get some basic familiarity with how nearby stones relate to each other. This would really take a whole article by itself, so comment if that’s something that you’d like to see!

Lastly, an idea you can try is to take for example a 9×9 game at different stages of play, early, midgame or endgame and try to remember and recreate the position at this point of the game. This is something I’ve done in my own lessons, and it’s quite different to just memorising a game normally, since you don’t care how the stones got there, but rather you just want to know which stones are there! One useful shortcut to remember a position like this is to use familiar Go shapes! Try to remember if there was a stone at the 2-2 and if a nearby stone was a diagonal (kosumi), or knight’s move away, if there were two or three stones in a row, or if there was a cross-cut and so on. This way you are practicing remembering Go shapes, and it should help you to remember shapes that appear often in your own and others’ games!

New Ideas

One thing in particular that makes reading difficult is simply not being able to think of or comprehend a move or idea. Do you remember the first time you came across a tesuji that you feel you never would have thought of in a game?

For me, the game of Go seems to provide endless new ideas, and each time I think I’ve learned quite a lot about the game, something new surprises me in a variation, book, video, puzzle and so on. On that note, this is exactly how you can come across new ideas: play games and have your opponent show you, take courses or do puzzles here on Go Magic or elsewhere, read books, watch videos and streams, the list goes on.

Focusing on material aimed at your level might be the best way to learn ideas that are likely to show up in your own games. However, almost any Go content should be able to provide you with something new to think about. Alternatively, it might motivate you to study something you’ve been putting off for a while, that one joseki you keep forgetting, that tsumego shape that keeps causing you problems or that everyone says is important to know by heart!

Improving Evaluation

One last idea worth mentioning is board evaluation. This is something which complements reading and helps decision-making, even though you might not think of it as “reading” in and of itself. Every time you read out a sequence, at the end you need to think to yourself “Who is this good for?” or “Is this about even or a fair result?” to decide if the sequence is worth trying. It can be annoying to spend time reading only to have your opponent tenuki, or to find a simplifying move that negates a lot of what you were reading.

Decision-making and evaluation are important and a little trickier to train, but they should help you decide on for example: which stones are important, if sente to tenuki is important, who is leading, is the fighting here good for one side or another, do I need to invade here or can I reduce and still win etc.

If you want to improve your board evaluation, then some ways to train this include:

- Reviewing your games, by yourself, with AI or with stronger players,

- Watching commentaries from strong players or pro players,

- Doing whole board puzzles,

- Practicing counting during the opening, middle and endgame stages

And now?

Are you feeling ready to improve your reading? Check out the Go Magic skill tree, which has a huge range of problems for improving reading. There are tsumego, tesuji and endgame problems, visualisation problems which hide the played stones or where you need to make a decision without playing any stones at all and of course, some whole board judgement problems! You should also check out the wide range of courses on offer, with video instructions and puzzles to test the new skills you’ve learned!

Accurate reading, my weakness 😢

Also, I’d very much like to see an article about shape, in continuation of this one!

Excelente contenido para mejorar las jugadas en go Agradecida.

Great article. Lots of homework to do. Thanks

Excellent article. Going to try one of them and see. Interested in shapes 🙂

Messages and information received with gratitude heart 💓

Billions Thanks for wonderful article.

Excelente artículo! Que se venga pronto Go Shape Nivel 2! :))

Several useful and interesting concepts- first action I am going to take is reread to help it sink in.