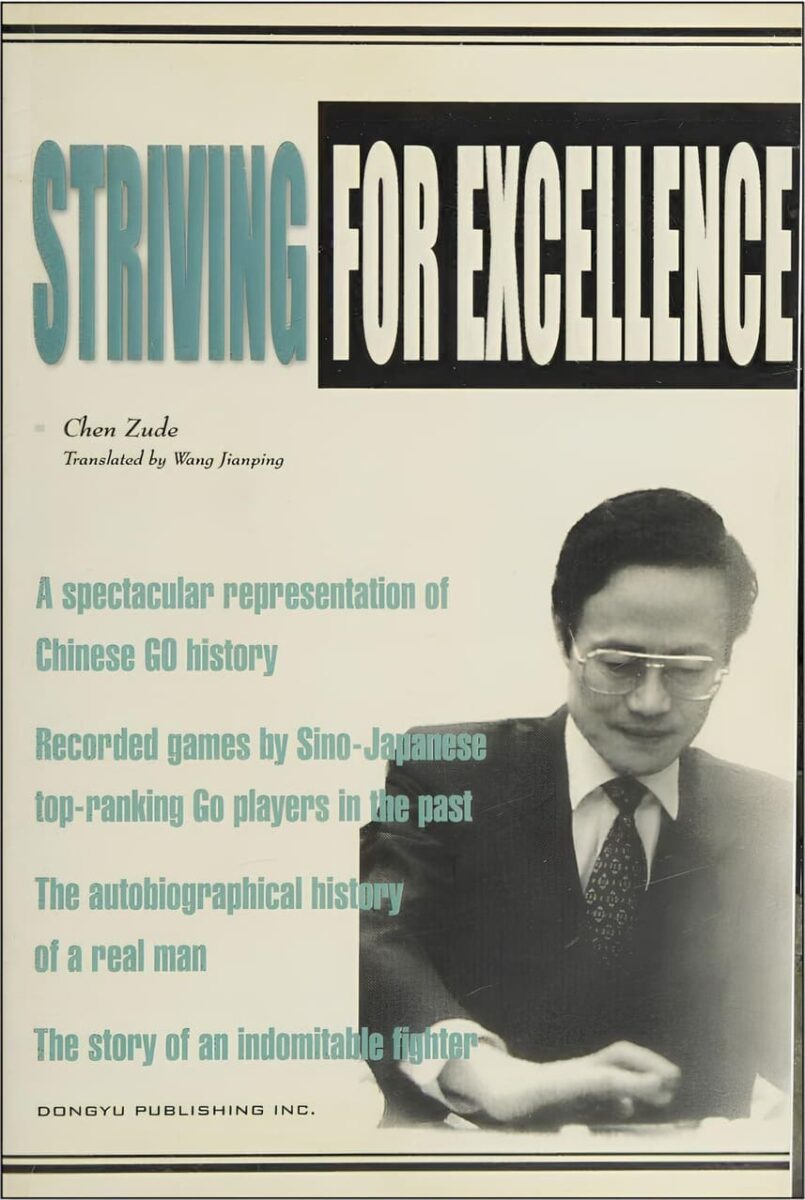

Learning From Pro Autobiographies, Part 1: Striving for Excellence by Chen Zude

“War is vivid only through artistic creativity in fiction, painting, and movie. In actuality, injust war brings only scarcity, pain, disaster, darkness and death. I wish there would be no more wars in this world, no more militarists and politicians who produce wars but only artists and scientists. If anyone is interested in wars, let him do it on the [Go board].”

Introduction

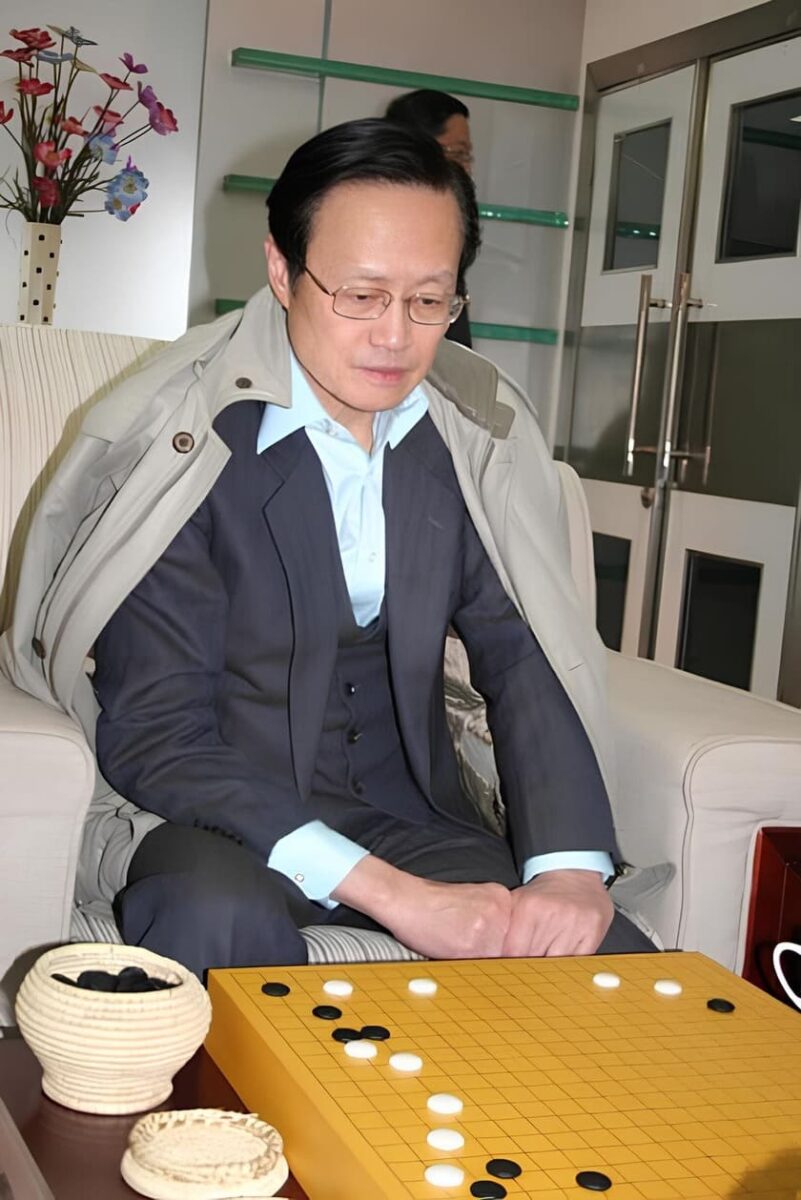

Chen was the first Chinese player to reach 9-dan after the introduction of the modern professional system in China. He was one of the most important promoters of Go in China both as a top professional and first President of the Chinese Weiqi Association (中国围棋协会). He was an innovative player and the main exponent of the Chinese fuseki. By using his unique style, he was the first Chinese able to defeat 9-dan Japanese professionals in the 1960s. His success was abruptly interrupted by the Cultural Revolution, during which he was sent to a political camp and later became a worker in a factory.

Written while Chen was hospitalized for cancer surgery, his autobiography offers a memorable glimpse into the spiritual world of an outstanding sportsman who came of age with the birth of the Republic and who witnessed—and greatly supported—the growth of Chinese Go as a professional game.

Heritage and Legacy within Continuous Unfolding

Chen Zude’s autobiography is like a Taoist painting. Zude not only writes about his life from early age to his death bed, but also about the effervescent history of Go in China. As with other player biographies, we are taken through important Go events, follow memorable games, and encounter life and Go-related lessons that took the authors years, or even a lifetime, to learn. What elevates Zude’s autobiography to the level of art is the way it introduces us to a cast of characters—both real and mythical—the way we savor the unfolding of events and the customs of a distant land. Zude’s China, in fact, may be unfamiliar even to many modern Chinese readers. The book allows us to commemorate the tragic weight of the past while witnessing a relentless pursuit of personal growth and hope for the future. All of this is seamlessly interwoven into a deeply human narrative. A single Go stone holds no meaning on its own; its significance emerges only in relation to other stones, through patterns and sequences that shift within ever-changing contexts. In the same spirit, this book is not only about Zude himself, but about his evolution, the people who shaped him, the spirit of the times, and the cultural texture in which it all unfolds.

Chen Zude’s childhood, his introduction to Go, and his early training reflect the modest spirit of the era in China. His path toward a professional Go career was far from straightforward—almost as if fate were toying with him. Choosing Go was neither easy nor instinctive for Zude. He had to give up his dream of becoming a painter and leave his part-time job at the shipyard. Even then, he remained uncertain until his father—who had first taught him Go at the age of seven—guided him toward the final decision.

Throughout his journey, many influential figures are introduced, each portrayed with care so that their presence leaves a lasting impression on both Zude and the surrounding context. Zude consistently expresses deep respect and gratitude for his mentors. These included his father, Zhou Jiren, Gu Shuiru, Liu Lihuai, and Wang Youchen. Notably, Mr. Gu Shuiru accepted only two students in his lifetime: Wu Qingyuan (better known in Japan and the West as Go Seigen) and Chen Zude. Unsurprisingly, Wu Qingyuan—the Go player the author admires most—is described as embodying a style that is “magnificent, light, casual, and fresh.”

Starting with a large handicap, Zude’s and correspondingly Chinese Go made slow and steady progress. At the beginning Sino-Japanese games were always unequal and ended in crushing defeat. But as Zude notes, “failure is the mother of success”. Zude evolved through study coupled with the courage to abandon established masters or manuals. Thus, he developed his own distinct approaches, aimed at being initiative and anti-traditional.

Zude’s life is defined by a deep devotion to the game of Go and a strong sense of patriotism. He regarded Go as a national treasure, and saw his achievements as contributions not only to China’s reputation in the international Go community, but also to the development of the game within his own country. Readers are invited to relive some of his most memorable and emotionally charged matches, witnessing his growth as a player—culminating in victories over several top Japanese professionals. Remarkably, Zude became the first Chinese Go player in the modern era to achieve the prestigious rank of 9 dan.

Hardship recurrently seems to reemerge in sagas like the one we are following. Zude’s ascension is cut short by the Cultural Revolution. This period brought immense personal hardship, forced him to stop playing Go for seven years, and saw the persecution of many, including his father and fellow Go enthusiasts.

In his later reflections, Chen Zude comes to see his personal story not merely as a solitary journey, but as inseparable from the rise of Chinese Go itself. “The history of my professional career has been closely linked with the history of New China’s Go development,” he writes. His triumphs and setbacks, like those of the country he so dearly served, were both personal and collective. The hardships he endured—from the early defeats in international matches to the enforced silence of the Cultural Revolution—are not just part of his own growth, but part of the greater unfolding of a cultural legacy. His memoir becomes, in this sense, a moral and historical document—an act of witness and service. As Zude puts it, “It is my duty to record everything I have witnessed.”

Rather than resisting the passage of time, Zude embraces the transition from player to elder statesman of the game, taking pride in being surpassed by the next generation. “In the cause of Go, I am a transitional person, and for that alone I should pride myself,” he writes, with clarity and humility. No longer defined by competition, he reimagines himself as a “Go worker,” contributing to the vitality of the game through mentorship, institutional leadership, and memory. For Zude, the art of Go remains a living, evolving force—“changing constantly. Its vitality lies in its capacity for change.” This view also fuels his eventual acceptance and even pride in being surpassed by younger players like Nie Weiping, seeing it as necessary for the sport’s progress. “I am aware that my life does not belong to me alone,” he admits. And in that spirit, his legacy remains open-ended: a stone placed not for itself, but for the future shape of the board.

Innovation and Striving

Chen Zude’s legacy as a Go player is inseparable from his relentless pursuit of innovation and independence of thought. From early in his career, he rejected the notion of blindly imitating stronger players, insisting that true progress could only come through developing one’s own style. “I would rather fail because of innovations than refrain from creating new things being afraid of failure,” he once declared—a philosophy that underpinned both his bold play and his broader contributions to Go theory. Zude’s most well-known innovation, the Chinese stream opening (also known as Chinese fuseki), was not born from theoretical abstraction, but from the practical need to challenge convention and gain initiative. It was a tool for opening up new directions in the game, a concrete expression of his belief that Go should remain fluid, evolving, and free from dogma.

But Zude’s striving was never purely technical. His commitment to innovation was deeply intertwined with his broader attitude toward life and learning. He approached study with discernment, analyzing not only the strengths but also the flaws of even the greatest players. Ancient Chinese Go manuals left a lasting impression on him—not only for their tactical clarity and fighting spirit, but for the cultural ethos they embodied: courage, ingenuity, and directness. In these manuals, Zude saw a mirror of his own ideal—an unyielding will to confront weakness and transform it through effort. “Life is a continuous process of discovering one’s mistakes, errors, weaknesses” he wrote, “a process of transcendence.” For Zude, Go was never separate from the self. Mastery of the game was part of a greater moral and psychological journey toward clarity, responsibility, and strength.

Zude’s ambition, however, was never about personal glory alone. He strove to elevate Chinese Go as a whole, to break through the barriers of inferiority that once defined China’s position in the international scene. Even as he achieved the highest professional rank and defeated top Japanese players, he remained self-critical and forward-looking. When the Chinese stream opening became fashionable and overused, Zude distanced himself from it, warning against the very rigidity he had once sought to overcome. Innovation, in his view, was not the production of novelty for its own sake, but a disciplined, purposeful rebellion against stagnation. As he wrote in his later years, “Only in this way is one able to develop, to break through, and to surpass one’s limitations and move into the kindgom of freedom.” This commitment—to renewal, to struggle, and to transcending one’s own past—remains at the heart of Chen Zude’s legacy as both a player and a human being.

Knowing to Lose

For Chen Zude, losing was never a mere outcome—it was an arena for transformation. His early defeat in the 1959 city contest, caused by a suicidal mistake in a winning position, marked the first deep lesson in vigilance and humility. From that moment, he understood that Go is a game of fine edges, where one lapse of concentration can unravel hours of dominance. Losses such as these, often magnified by the pressures of competition and public expectation, were not humiliations to be buried but confrontations with reality that forged resilience. In a telling anecdote, he reflects on the hour-long move against Wei Xi—an extravagant experiment driven by overconfidence—that ultimately led to defeat. Yet, the story isn’t told with shame, but with a tone of respect for the depth and difficulty of serious play. Knowing how to lose, for Chen, began with knowing how to look directly at failure and not flinch.

At times, the emotional weight of loss exceeded the boundaries of the game itself. His relationship with his mentor Wang Youchen provides one of the most human portraits in the memoir: Chen was urged by Wang to win a championship match, only to be defeated when Wang’s own instinct to compete prevailed. Chen felt betrayed, but later recognized the deeper lesson—that promises and sentiments dissolve before the pure instinct of the game, and that even the closest of mentors will fight for their place on the board. Even more poignant was a final game Chen won against Wang shortly before his death, a victory that later filled him with regret. These episodes reveal a man who carried his defeats—and his victories—with conscience. To Chen, losing was not just about stones on a grid, but about missed chances for grace, humility, or reverence.

Beyond the board, the greatest losses of Chen’s life came during the Cultural Revolution. The suppression of Go, the dissolution of the national team, and the persecution of intellectuals—including his own family—cut through his formative years as a professional. He lost time, opportunity, and nearly the game itself. Yet even here, Chen finds a paradoxical depth: in manual labor and rural exile, he gained insight into the struggles of ordinary people, which broadened his moral and spiritual outlook. Later, battling cancer, he returned to Go as both a player and a writer, composing his autobiography in hospital, still committed to expressing the meaning of a life entwined with the game. “I would lose in grace if I cannot win in glory,” he wrote—not as resignation, but as resolve. In Chen Zude’s story, knowing how to lose became the path to winning something greater: perspective, maturity, and peace.

Game: ‘Chinese Stream’ wins versus Kajiwala in Japan-China Go Exchange

“Kajiwala” (8 Dan, but described as playing at level of 9 Dan) was the main opponent faced by Chen Zude in 1964 and 1965. The name appears consistently through the autobiography. This seems to be a phonetic transliteration from Chinese, where “r” and “l” are often interchangeable because it refers to none other than Kajiwara Takeo.

In 1964, Kajiwala was a little hesitant in visiting China where he used to serve in the Japanese army during the Anti Japanese War.

In his speech, he said, “I had participated in the Japanese aggression against China, but as a soldier I always shot into the sky.”

Zude characterizes him very favorably both for his Go strength and for this character. The author doesn’t miss the opportunity to compliment the prestigious playing style of his opponent, called the “Kajiwala stream”. You can learn more about it in the Go Magic course about the style of Kajiwara Takeo where it is also referenced as the “Nothing Style”.

Zude used the “Chinese Stream” versus Kajiwara in the previous Japan-China Go Exchange (1964). Although he suffered losses, he considered his opening established as a major techinque as “Kajiwara had won the game but he had not discovered an efficient way of countering “Chinese Stream.”

Zude describes previous games as well as all three he played versus Kajiwara in the 1965 Japan-China Go Exchange:

- 1st game as Black (12 April 1965), Zude used Chinese Stream successfully but lost in middle game after referee allegedly overlooked the byo-yomi time violation by Kajiwara.

- 2nd game as White (18 April 1965), Kajiwala admitted defeat by 0.5 points according to Japanese scoring, but the score was determined by Chinese regulation so it was a draw (jigo) – ever so modest through his book, Zude chose this game record to share in his biography out the three.

- 3rd game as Black (20 April 1965), Zude used Chinese Stream gaining the upper hand right at the start and overwhelmed White in the middle game, forcing Kajiwala to resign – less modestly, this is the game that we chose to present.

Conclusion

Chen Zude’s autobiography is far more than a personal memoir—it is a cultural document, a moral testimony, and a philosophical meditation on growth, loss, and legacy. Through his life story, we witness not only the rise of a Go master but also the turbulent evolution of modern China and its reclaiming of an ancient art. His reflections reveal a man who lived and played with purpose, who saw Go not as a game of mere territory but as a path toward self-mastery and cultural renewal. From early struggles to historic victories, from deep personal betrayals to redemptive insights, Chen’s voice carries both the humility of someone who has known defeat and the quiet confidence of someone who has shaped history. His contributions to Go—as a player, innovator, mentor, and chronicler—continue to ripple through the present. As we place our own stones on the board, Chen’s life reminds us that excellence is not defined by domination, but by transformation; that to play well is to live meaningfully; and that true legacy, like a well-placed stone, shapes the game long after the hand that placed it is gone.

Such a nice article. Good Job ❤️

Thank you, SoumyaK4. I am working on the next two in the series. The third will take a little longer. Hope you enjoy those as well <3.

Puede ser que confunde a Chen Zude con Nieh Weiping?

Saludos

Hi. Thank you for taking an interest. I am not sure why they would get mixed up, but they do share some similarities.

Both Chen Zude and Nie Weiping are absolute legends, but they represent different generations and have distinct roles in the history of Chinese Go (Weiqi).

– Chen Zude is like the pioneer who built the foundation and broke the first barrier – the psychological barrier of being able to compete against Japanese players on equal footing.

– Nie Weiping is like the superstar who scaled the peak and planted the flag for everyone to see – he demonstrated that China could not just compete, but win.

Chen Zude’s success made Nie Weiping’s possible. While their careers overlapped, Chen was the respected elder statesman, and Nie was the dominant champion of his era.

Muchas gracias por su respuesta