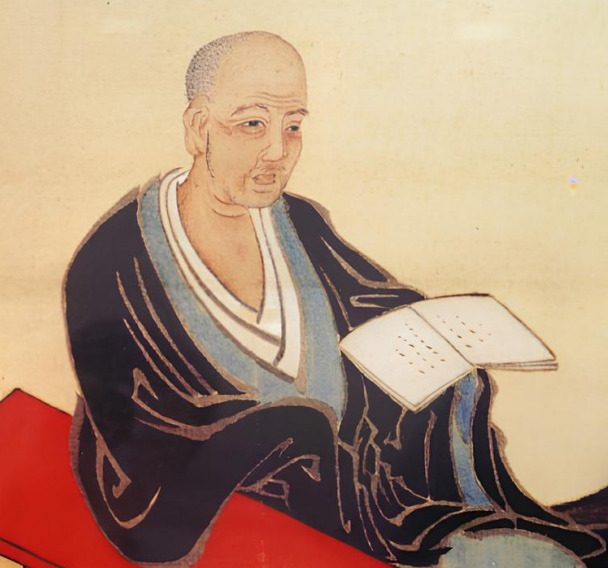

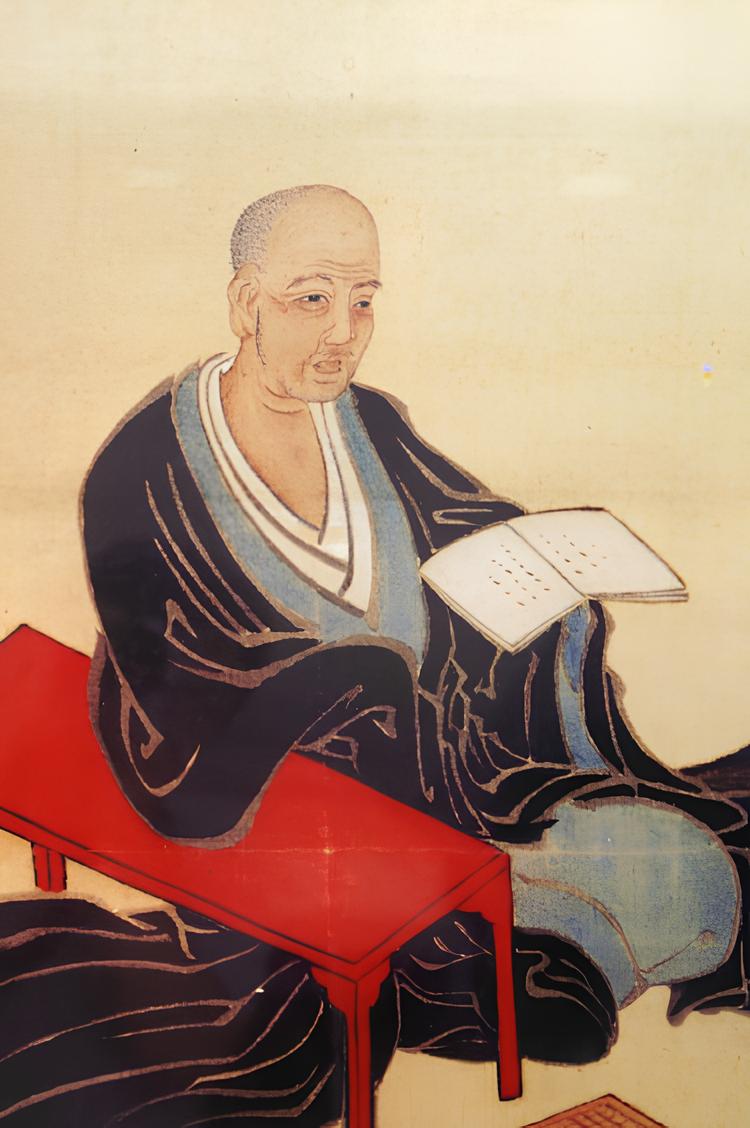

Dosaku – The Go Saint

Picture Souce: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hon%27inb%C5%8D_D%C5%8Dsaku

Let’s discover together how a boy born in a provincial town in 17th century Japan rose to become one of the most influential Go players in history and eventually be conferred the title of “Go Saint” (Gosei).

We will reveal everything about his life, career, and enduring legacy, so our reverence article, we hope, will bring some well deserved praise and we will honour him this way.

Early Life and Background

In the year 1645, in the remote Iwami Province (present-day Shimane Prefecture), in the far west of Japan, a child named Yamazaki Sanjiro entered the world. Later he was going to take the name of Dosaku. We do not have any clear historical records on his family background but most likely came from a modest family rather than nobility or samurai descendants.

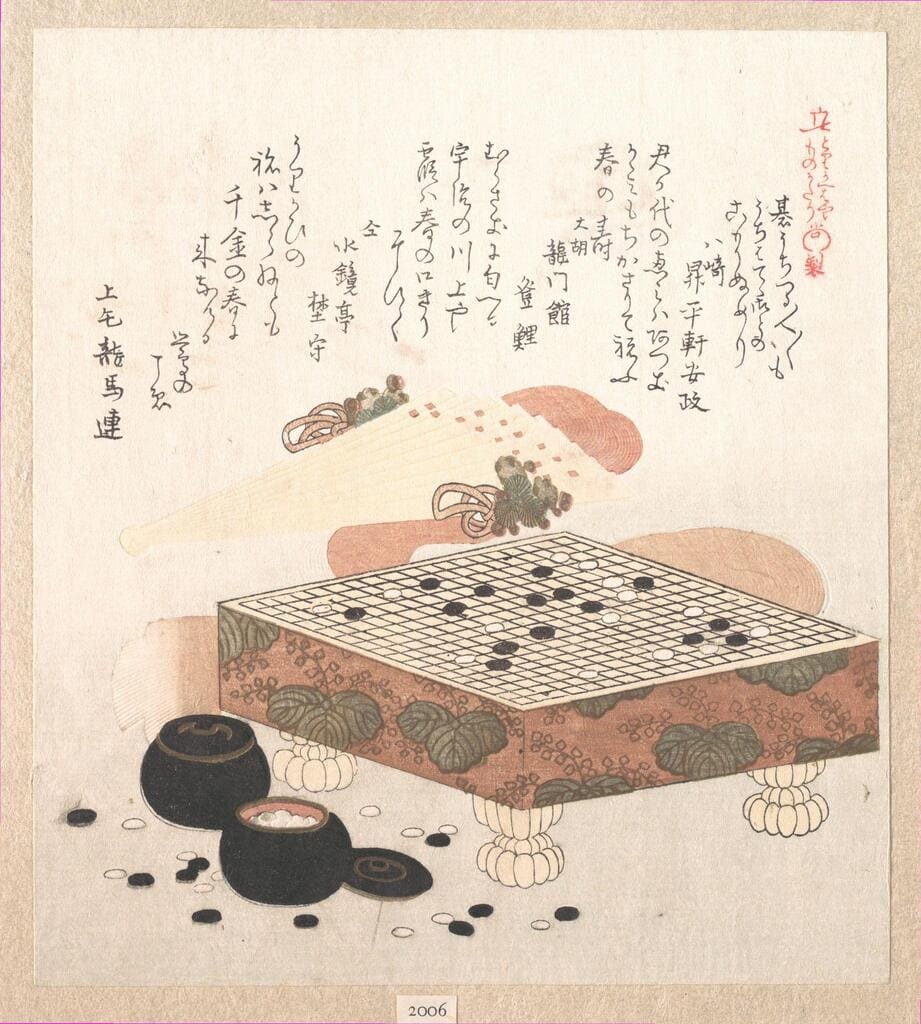

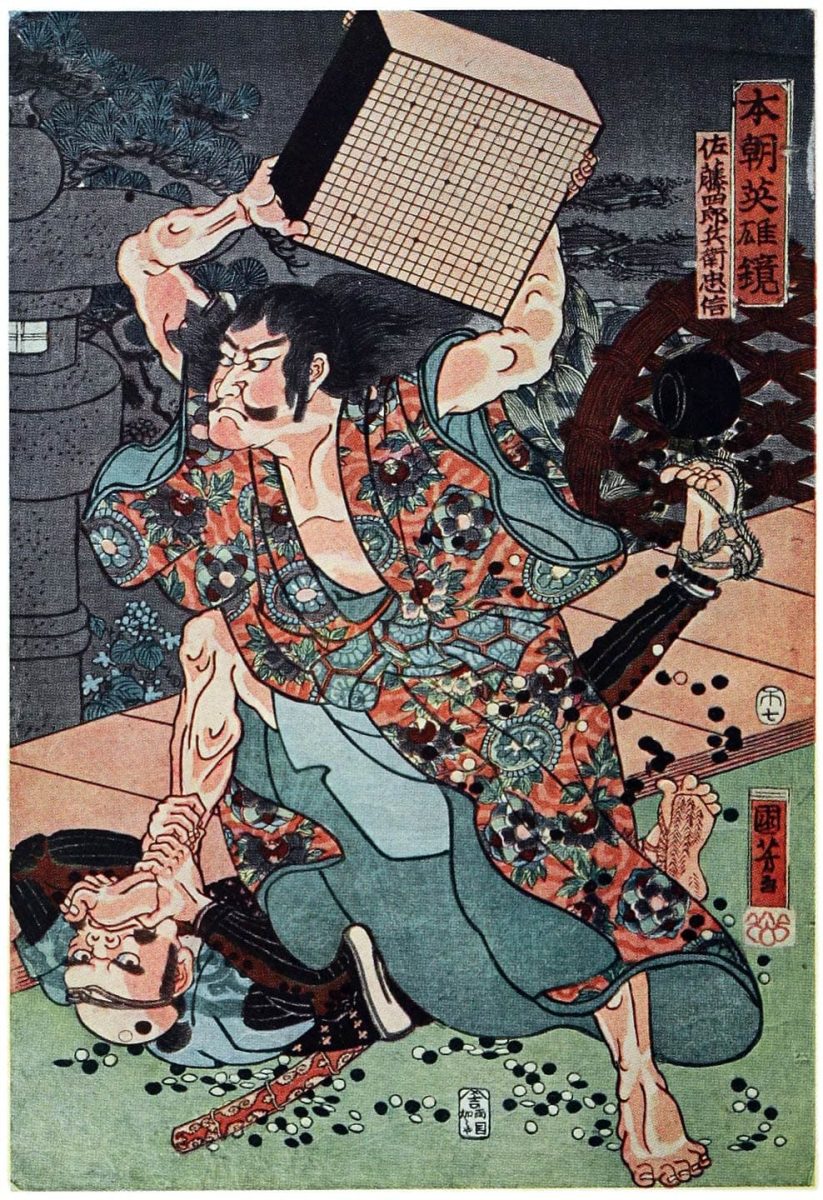

To better understand Dosaku’s life and evolution, we need a bit of a historical context of The Edo Period (1598-1868), during which he lived, and which period represented an evolution from the centuries of civil war to a period of relative peace and stability under the Tokugawa shogunate, who established his government at Edo (Today’s Tokyo), in 1603. It was a time when Japan closed itself off from the outside world through the sakoku (closed country) policy. Internally, though, due to the peace, the cultural life started to develop and we have the historical records to see that in many areas of life: the merchant class rising in influence, arts such as kabuki theater, ukiyo-e woodblock printing, and various traditional games including Go started flourishing.

(source: Japan | Edo period (1615–1868) | The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

At the time of his birth, Go had been established in Japan for almost a millennium, being known since the Nara period (710-794), when it was introduced from China. By this time, it evolved into a sophisticated game with professional players organized into houses or schools (iemoto system). Four main Go houses have developed during this time: Honinbo, Yasui, Inoue, and Hayashi and they competed for prestige and patronage, particularly from the shogunate, which officially recognized and supported Go as a cultural institution.

We believe that Yamazaki Sanjiro first encountered the game of Go at the age of seven, but there are no historical accounts that specify who introduced him to the game or provided his initial instruction. We know though that he had remarkable aptitude from an early age for the game and at 15, he had already reached the rank of 5 dan, which was a significant achievement given the slower advancement norms of the era, when 1 rank was gained every two years. Anecdotal records describe how he excelled at whole-board evaluation, a skill that distinguished him from contemporaries who often focused on local tactics.

Considering the cultural context and the competition between the Go houses, it is no surprise that his talent became evident to attract the attention of Honinbo Doetsu, the third head of the prestigious Honinbo house, who took him as a disciple. This was a recognition for his remarkable potential and it was at this point that Yamazaki Sanjiro acquired the name Dosaku, following the common practice of disciples taking a name that incorporated a character from their master’s name (in this case, the “Do” from Doetsu).

The Honinbo house had been founded by Honinbo Sansa in the late 16th century and it was already one of the most prestigious Go schools in Japan. Each of the 4 schools had their own style and philosophy behind the game.

| House | Known For | Style Highlights | Notable Figures |

| Honinbo | Dominance, innovation | Whole-board strategy, fuseki theory | Dosaku, Shusaku, Jowa |

| Yasui | Rivalry, political maneuvering | Tactical sharpness, local fighting | Yasui Sanchi |

| Inoue | Stability, tradition | Conservative, precise play | Inoue Inseki line |

| Hayashi | Supportive role, tradition-keeping | Less distinct, aligned with Honinbo | Hayashi Monnyu |

The Honinbo house philosophy behind the game playing approach of solid, territory-oriented play and precise reading of tactical sequences, would become the foundations from which Dosaku would launch his own innovations and refinements to Go theory.

As a disciple in the Honinbo house, Dosaku was probably demanded to perform household duties in addition to his Go studies, but it provided an immersive environment for developing both technical skills and the mental discipline necessary for mastery of the game. During these years, as a disciple, most probably that Dosaku was exposed to the distinctive playing style and theoretical approaches that characterized the Honinbo school. Dosaku’s ability to calculate long sequences and anticipate positional outcomes was noted as exceptional among the Honinbo disciples.

We know that the shogunate actively promoted Go as both a cultural art and political tool and the historical records from the Castle games are a strong reference to this case. Dosaku positioned himself as the leading figure in this competitive environment. His training and early successes had set the stage for his eventual appointment as the fourth head of the Honinbo house.

In the mid-1670s Doetsu prepared to retire, while Dosaku had become the natural successor to lead the Honinbo house.

Rise to Prominence

When Doetsu retired in 1677, Dosaku, at 32, became the 4th Honinbo head, bringing both technical mastery and a revolutionary vision for Go theory.

Professional Go in Edo Japan was highly competitive, with houses vying for shogunate favor. The most important title at that time was the Meijin Godokoro, a title attributed to players who not only demonstrated unmatched skill but also held influence at court. This environment shaped Dosaku’s development beyond technical skills into political strategy. Dosaku’s rise at the top of the Honinbo house was both a personal and political process.

(Source: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/66632/66632-h/66632-h.htm)

During this time, the main rival of the Honinbo house was Yasui house under Santetsu II, who held the Meijin Godokoro title between 1668-1676; the games, Dosaku, played against members of this house have remained in the history of the game and we will look at some of them in a later chapter.

In 1678, one year after becoming the head of Honinbo house, Dosaku was also appointed Meijin Godokoro, which was an unprecedented unanimous recognition of his superior skill in an otherwise contentious competitive landscape.

Why was this title so important? The Godokoro (literally “Go office”) was the officially appointed position of the top Go player who served as an advisor to the shogunate on all Go matters. It was a position of both honor and political influence.

The Meijin Godokoro position provided an official platform from which he could further develop and disseminate his theoretical innovations.

The Ranking System

The Meijin Godokoro position brought prestige, but also significant responsibilities and influence; Dosaku’s task of overseeing the Castle Games, official matches held at Edo Castle before the shogun or/and high-ranking officials, inspired him to organize and shape the professional Go system.

The kyu/dan ranking system had earlier origins, possibly in earlier Chinese ranking systems, but during the Edo period, ranks were often assigned based on house affiliation and politics, rather than skill and Dosaku decided to change that.

Dosaku’s idea was to establish a more merit-based and standardized approach to professional rankings that transcended house politics. He formalized the criteria for the advancement through ranks which helped create a more objective ranking system.

As Meijin Godokoro (the official head of the Go world recognized by the shogunate), Dosaku had the authority to implement these changes across all houses, not just within the Honinbo school. He influenced the houses to accept the player’s advancement to be more tied to demonstrated skill than house affiliation and political connections.

Dosaku worked within the constraints of his time and his new approach still operated within the four-house structure, so the houses continued to have a significant influence, but his system constitutes the basis of the way the rankings are awarded and his fully independent, merit-based system, we see today, evolved gradually, over the centuries, from these foundations established by Dosaku.

Playing Style and Innovations

As Meijin Godokoro, he used to play in the Castle Games against some of the most prominent members of the other houses, like the rival Yasui house, particularly Yasui Chitetsu and Yasui Santetsu II (also known as Yasui II Sanchi).

The games that survived and we have access to them today reveal a player who blended tactical and strategic insights, technical precision and creative flair, theoretical innovation and practical mastery.

Studying his games you will discover Dosaku’s ability to outmaneuver even the most respected players of his time, highlighting his growing dominance and refined tactical skill.

One such famous game is being reviewed and commented on here: Redmond’s Reviews, Episode 24: Honinbo Dosaku vs Yasui Santetsu (The Tengen Game). which is said to display “one of the most elegant sequences in classical Go”.

Honinbo Dosaku revolutionized Go through exceptional tactics and strategic innovation, by sacrificing local positions for greater global advantage, demonstrating remarkable balance between tactical considerations and strategic objectives.

Tewari Analysis and Dosaku’s Innovations

His most significant theoretical contribution was pioneering “tewari” analysis (“hand division”), which is a method of move-order evaluation that helps players determine if a sequence of moves is efficient or contains unnecessary steps or redundancies. It breaks down complex sequences to see if moves could be rearranged for better local efficiency or positional gain. This systematic framework for evaluating moves transcended intuitive judgment and became a teaching methodology that preserved his insights for future generations.

While Dosaku did not invent tewari analysis explicitly, his emphasis on efficient shape and whole-board judgment laid the conceptual groundwork that tewari later formalized. His play style reflects careful consideration of whether moves contribute meaningfully to the overall position, a key idea behind tewari.

Dosaku’s focus on shape and positional efficiency aligns with tewari’s goal of identifying inefficiencies in sequences. In essence, his moves often demonstrate the kind of refined, minimal placement that tewari analysis highlights.

Amashi Strategy and Dosaku’s Style

Dosaku improved “amashi” strategy (“allowing”), where one player “encourages” the opponent to build territory while developing powerful positions with greater future potential.

So, amashi is a strategic approach that prioritizes letting the opponent build territory on the sides or corners while focusing on building strong influence and controlling the center, often aiming for a higher territorial yield in the long run.

Dosaku’s innovations in direction of play (kidō) and fuseki show early forms of amashi thinking. Instead of aggressively invading corners or chasing immediate territory, he often focused on building frameworks (moyo) and influence, trusting in strategic timing and positional judgment to convert that influence into profit later.

His balanced, whole-board perspective can be seen as a precursor to amashi-style strategy, where restraint and positional pressure override early territorial grabs.

Opening Techniques (Fuseki) and Dosaku’s Legacy

In opening theory, he developed the “three-space low pincer”, which exemplified his balanced approach by providing both territorial potential and influence while maintaining flexibility. His opening innovations reflected a coherent strategic vision connecting all phases of play.

Dosaku’s opening innovations of moving away from rigid, local corner sequences toward more flexible, balanced fuseki, directly impacted how openings are played today.

He pioneered a mindset that views the opening as a coordinated effort to develop the entire board’s potential, not just securing isolated corners. This broad strategic approach supports both amashi concepts and the later development of flexible fuseki patterns.

These innovations dramatically increased his strength, making him approximately two stones stronger than his nearest rivals. Future generations estimated he played at a 13-dan level when the highest official rank was 9-dan.

| Technique | Relation to Dosaku’s Innovations |

| Tewari analysis | Builds on Dosaku’s emphasis on efficient shape and move order evaluation, highlighting positional efficiency. |

| Amashi strategy | Reflects Dosaku’s preference for influence-building and strategic restraint rather than early territorial grabs. |

| Opening techniques (fuseki) | Directly influenced by Dosaku’s flexible, balanced whole-board approach to opening play. |

Leadership in Go requires both competitive strength and strategic vision. Understanding and incorporating these concepts of efficient move order, influence over territory, and flexible fuseki development deepens appreciation for Dosaku’s innovations.

Legacy and Influence

Honinbo Dosaku’s legacy stands out in two key areas: his innovations in Go strategy and his influence on the institutional development of the game.

Dosaku’s legacy on the Game of Go

His teaching and theoretical innovations: tewari analysis, amashi strategy, and opening techniques have become fundamental to Go strategy and tactics. Perhaps this is Dosaku’s most profound legacy demonstrating Go’s possibilities of integrating tactical brilliance with strategic depth, balancing tradition with innovation, and combining competitive success with theoretical advancement. He showed that Go is not merely about calculation but a field for creative expression and intellectual exploration.

He was also a master and a teacher and he instructed numerous and influential pupils, including the talented “Five Tigers” (Hoshiai Hasseki, Inoue Dosetsu Inseki, Kumagai Honseki, Ogawa Doteki, and Sayama Sakugen), ensuring his insights would be preserved for future generations. The historical records are fragmented and we do not have very clear data on what his disciples achieved, but they all took Dosaku’s teaching and developed them in some new ways, like codifying Dosaku’s style into house instruction manuals (Doteki) or helped to transmit Dosaku’s fuseki innovations (Kumagai Honseki). Their games, particularly those of Doteki, remain valuable historical records that provide insight into Dosaku’s school of thought and playing style.

Approximately 150 of Dosaku games have survived the centuries and they are today valuable resources for our generations to study and understand the evolution of the game.

These games “rediscovered” in the 1990s led to renewed appreciation of his genius and today’s famous players commenting and discussing games from 300 years ago and we will discuss a few of such games in the next chapter.

Dosaku’s Impact on the Institution of Go

Under his leadership, the Honinbo house achieved unprecedented prominence, with the Honinbo title becoming one of professional Go’s most prestigious, continuing unbroken until the 20th century.

But more than being just the Honinbo’s House head, his regularization of the Castle Game system provided a formal framework for high-level competition, while his contributions to the professional ranking system created merit-based advancement standards that influence Go organizations worldwide today.

The “Go Saint” (Gosei) Title

The game community recognized his profound influence through the rare title of “Go Saint” (Gosei) (Dosaku at Sensei’s Library), which they bestowed upon him for reshaping Go permanently.

This recognition emerged gradually, with historical records showing that Go scholars began using this honorific to acknowledge Dosaku’s exceptional innovations, during the Meiji period (1868-1912).

Then the title gained official status in the early 20th century when the Nihon Ki-in (Japan Go Association) formally recognized it during their efforts to document Honinbo school history and to create a permanent record of Go’s most influential figures in the Hall of Fame.

“Go Saint” (Gosei) is a prestigious honorific title in the Go world, typically reserved for players of extraordinary skill and influence who made fundamental contributions to the game.

For all of us, today’s Go players, we believe that Dosaku’s legacy offers both inspiration and instruction through games that remain relevant despite centuries of evolution in Go theory. His enduring influence rests on his unique combination of playing strength, theoretical innovation, and institutional leadership, making him truly worthy of the title “Go Saint” among the greatest masters in the history of this ancient game.

Notable Games and Analysis

Dosaku’s genius is most clearly revealed through his games. We discussed so far the historical accounts and theoretical aspects of his innovations and contributions to the game, which we hope that it provided valuable context to understand his mastery of the game, but everything is in the actual moves he played on the board.

This section examines several of Dosaku’s most significant games, analyzing the strategic concepts and moves that characterized his play.

We made a short selection of games, trying to cover different periods of his life and maybe you can discover his evolution of the thinning and approach of the game. Hopefully they can help you to discover key aspects of Dosaku’s approach to Go, from his tactical brilliance to his innovative strategic thinking.

However, use this as a starting point and use the links throughout this article to discover more of his games and analyse them in more detail, if you wish so.

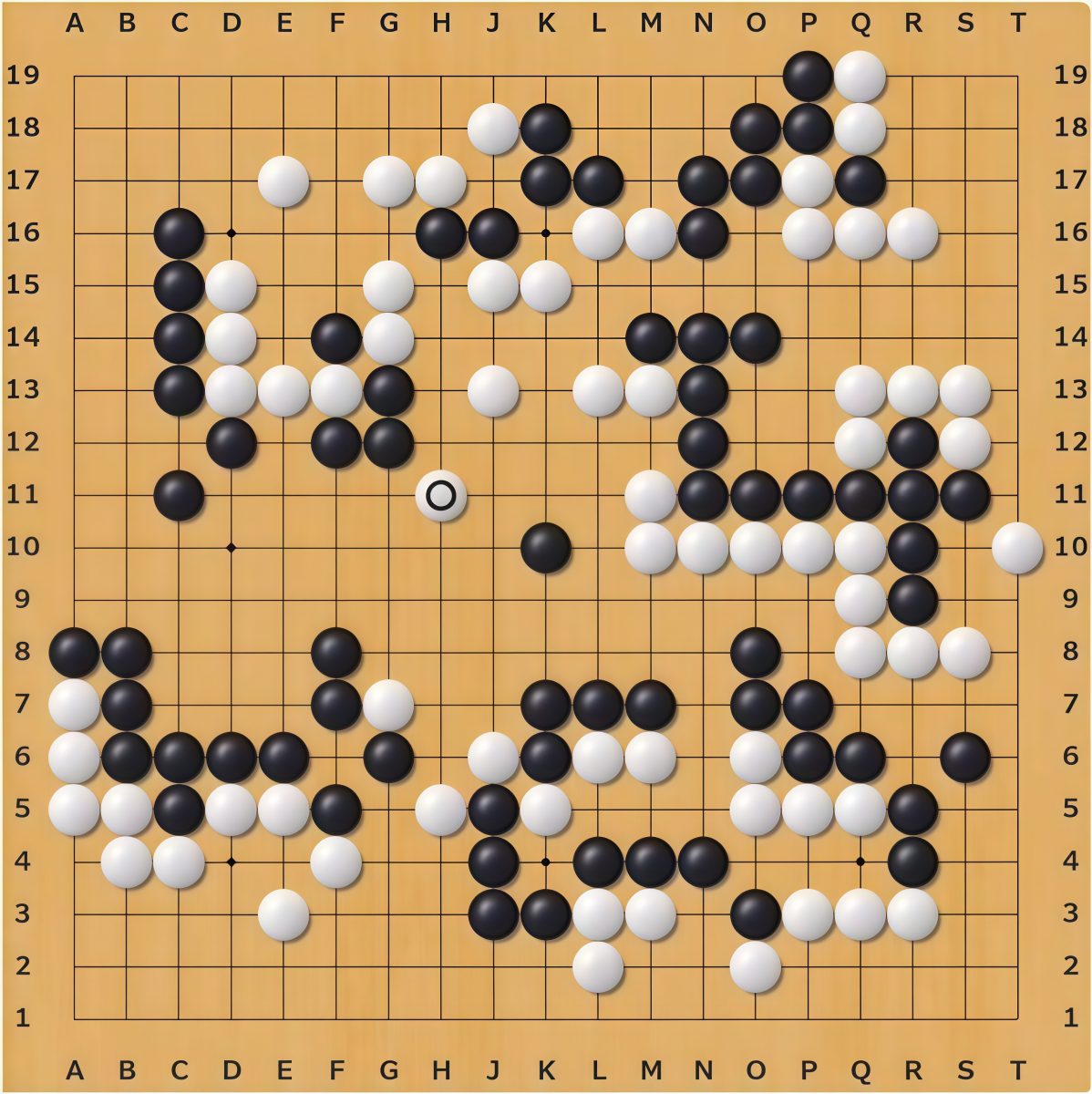

Game 1: Dosaku vs. Yasui Chitetsu (July 10, 1668)

One of Dosaku’s earliest recorded games was played against Yasui Chitetsu in 1668, when Dosaku was just 23 years old.

The game featured a complex middle-game battle where Dosaku demonstrated his exceptional reading ability and tactical acumen. In one particularly striking sequence, he sacrificed several stones to gain a strategic advantage, showing an early manifestation of the strategic depth that would become his hallmark. His willingness to trade local losses for global gains reflected a sophisticated understanding of whole-board strategy that was ahead of his time.

His flexible response to Yasui’s aggressive approach demonstrated a balanced understanding of territory and influence that contrasted with the more territory-focused style common in that era.

Game 2: Dosaku vs. Yasui Santetsu (September 16, 1669)

The game showcases Dosaku’s pioneering work in tewari analysis, with several sequences that demonstrate optimal move efficiency, attacking and sacrificing stones. Michael Redmond (9p) – in his video analyses of Dosaku’s games, and particularly in The Art of Sacrificing Stones of Honinbo Dosaku, Redmond specifically highlights sequences where Dosaku’s move order demonstrates an understanding of efficiency that was centuries ahead of its time. He notes that some of Dosaku’s sequences would be considered textbook examples in modern Go theory.

Game 3: Dosaku vs. Honinbo Doetsu (1670)

This remarkable game between Dosaku and his teacher Honinbo Doetsu, analyzed in Go World (Issue 11), available in the Go Database here: Honinbo Dosaku (1p) vs. Honinbo Doetsu (7p) provides a fascinating glimpse into the relationship between master and former student. At this point, Doetsu is still the head of the Honinbo house. The game was won by Dosaku B+R, but you can replay using the indicated link above for the beauty of it.

Particularly interesting is how this game illustrates the evolution of Go theory within the Honinbo lineage. Certain strategic principles and tactical patterns that appear in Doetsu’s play are refined and extended in Dosaku’s approach, showing how Go knowledge was preserved and developed through the master-disciple relationship.

Game 4: Dosaku vs. Yasui Shunchi (January 5, 1684)

This Castle Game against Yasui Shunchi, analyzed in Appreciating famous games – Books, is notable for Dosaku’s innovative use of the three-space low pincer in the opening. This technique, which Dosaku helped develop and popularize, became a fundamental part of opening theory and remains relevant in modern play.

“It is not clear whether Yasui Shunchi was the younger brother, son or pupil of Sanchi, the second head of Yasui family. But it is known that he took part in seven of the annual ceremonial games played in the Shogun’s palace.” (source: Appreciating Famous Games, Chapter 5). Against Dosaku, he always played black and in this game he took 2 stones handicap.

The game demonstrates Dosaku’s balanced approach to the opening phase, establishing a position that provided both territorial potential and influence while maintaining flexibility for future development. His handling of the middle-game fighting showed his tactical precision and strategic depth, with several brilliant tesuji that secured a decisive advantage. Dosaku lost this 2-stone handicap game, by 1 point, which the author says that it is almost beyond comprehension of how Dosaku was able to achieve that result and it is called his lifetime masterpiece.

As mentioned above, this game is particularly significant from a historical perspective as it was played as part of the official Castle Game system that Dosaku helped regularize. These matches at Edo Castle, played in front of the shogun or high-ranking officials, showcased the highest level of play but mostly reinforced the cultural and political significance of Go within Japanese society.

Final Words

Dosaku, as the 4th head of the Honinbo house, left his mark on the game development, building upon foundations established by predecessors like Honinbo Sansa and Doetsu, while as Meijin Godokoro he contributed to regulating the rankings which were the basis of what we have today.

In Japanese cultural history, Dosaku exemplifies the artistic and intellectual flourishing of the Edo period alongside figures like Matsuo Basho, Katsushika Hokusai, and Chikamatsu Monzaemon.

Ultimately, Dosaku’s historical significance lies in his role as a bridge between eras and approaches. He mastered traditional knowledge while developing revolutionary insights, operated within Edo-period institutional structures while establishing enduring principles, and achieved personal mastery while creating a legacy benefiting countless players across centuries and cultures.

In conclusion, probably you are asking yourself a few questions that we would like not to leave without an answer, so:

Was Dosaku the only one getting the title of Go Saint?

The short answer is no; there are other players who have been honored with the title “Go Saint” or similar honorific titles throughout Go history, though the title is quite rare and reserved for truly exceptional masters:

- Honinbo Shusaku (1829-1862) – Often called the “Invincible Shusaku,” he is frequently referred to as a Go Saint and is considered by many to be the greatest Go player in history alongside Dosaku.

- Wu Qingyuan (Go Seigen) (1914-2014) – While not formally given the title “Go Saint,” he is often mentioned alongside Dosaku and Shusaku as one of the three greatest players in Go history and is sometimes referred to with similar honorific terms.

- Huang Longshi (1651-1700) – A Chinese Go master who was contemporaneous with Dosaku and is sometimes referred to as a Go Saint in Chinese Go literature.

- Lin Hai Feng – A legendary figure in Chinese Go history who is sometimes referred to with saint-like honorifics.

The formal conferral of the title “Go Saint” has been relatively rare throughout history and practices have varied between different countries and time periods. In Japan, the title has been used very selectively, with Dosaku being one of the earliest and most prominent recipients.

The Gosei Tournament

It’s worth noting that in modern professional Go, there is a major tournament called the “Gosei” tournament, established in 1976, which uses the same characters as the honorific title of Go Saint and which is one of the seven major titles in Japanese professional Go, alongside the Kisei, Meijin, Honinbo, Judan, Tengen, and Oza; however winning the Gosei tournament doesn’t confer the historical honorific meaning of “Go Saint”; it’s simply named in honor of the concept.

Notable winners of the Gosei tournament have included top players like Cho Chikun, Takemiya Masaki, Rin Kaiho, and more recently, Iyama Yuta: The Architect of Modern Japanese Go.

This is a good example of how the legacy of historical Go figures like Dosaku continues to influence the modern professional Go world, with tournament organizers deliberately choosing names that connect to important historical figures and concepts.

What happened to the Honinbo house?

The Honinbo house officially dissolved in 1940, marking the end of over three centuries of continuous tradition. The decision was made by Honinbo Shusai, the 21st and final hereditary head of the house. Also, all the other houses have disappeared in time, with Hayashi first, not surviving to the end of the Edo period (1868) and Yasui and Ioue disappearing at the beginning of the 20th century.

Why did Honinbo dissolve you might ask?

There were a few reasons for which the 21st head of the Honinbo house took this decision:

- First of all the modernization of Go: By the early 20th century, the structure of professional Go was shifting from hereditary schools to open competition and merit-based tournaments. (also, all the other schools had disappeared)

- Then, the transition to tournament format: In 1940, Shusai transferred the Honinbo title to the Nihon Ki-in, Japan’s central Go organization, to be awarded through an annual tournament. This move was intended to preserve the Honinbo legacy in a modern, competitive format.

- And not last the cultural shift: The traditional iemoto (house) system was becoming outdated in a rapidly modernizing Japan. The new format allowed for broader participation and recognition based on skill rather than lineage.

So, the Honinbo title became the first major professional Go title in Japan to be contested through a tournament and it remains one of the most prestigious titles in the Go world today, with winners often adopting the honorary title of “Honinbo” followed by a chosen name.

The most recent Honinbo title winner (2025) is Ryō Ichiriki, who successfully defended his title against Shibano Toramaru with a final score of 3–2 (Go News – Japanese Honinbo)

“Gosei” is a modern tournament title in professional Go today, which is interesting given its historical connection to Dosaku.

What Do You Think?

Now that you’ve explored Dosaku’s life and his legacy and the strategic brilliance of his play, we’d love to hear from you: have you noticed similar ideas, like whole-board thinking or creative fuseki, in your own games or those of your opponents? Most probably you’ve been using these concepts without even realizing their historical roots.

How learning about Dosaku influences your perspective on Go? Do you see echoes of his style in modern play or in your own strategies? Let’s start a conversation!

Finally, this historical perspective and context of Go may resonate with other people in your circle. Consider sharing Dosaku’s story with fellow players and it might even Spark Your Friend’s Interest in Go.

This was an enjoyable article to read. As a thoroughly inexperienced player the article makes me want to learn so much more, I feel like that would increase the appreciation for legendary games and their players. Thanks for stimulating my desire to improve!

We really appreciate your comment and thank you so much for sharing this! The great thing is that every player, beginner or advanced, can enjoy these timeless games. Go has such a rich history, and exploring the games of past masters like Dosaku is a wonderful way to deepen your appreciation. Enjoy your journey! If you keep playing and exploring, you’ll find even more appreciation for the creativity of the masters. Thank you again for your kind words!