Go’s Greatest Rivals

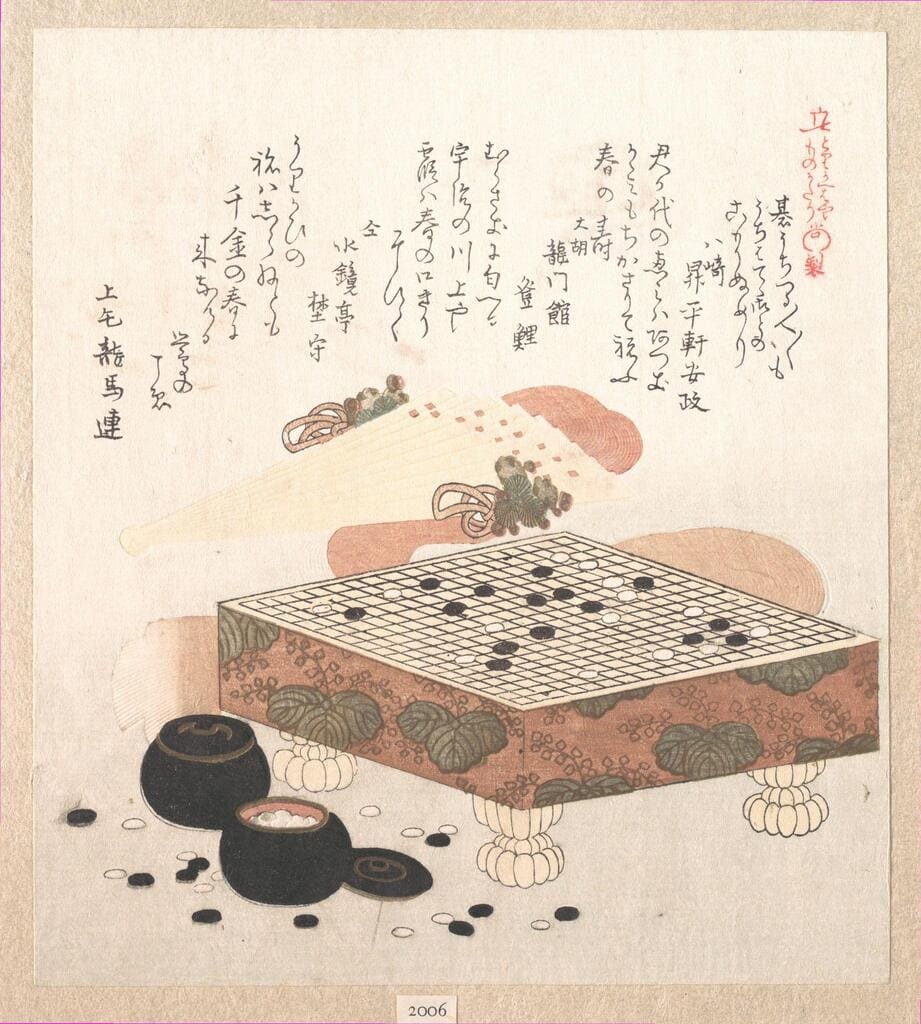

In this ancient game of war that rages on after thousands of years, one vital ingredient has ensured its continuous evolution: rivalry. It’s the magic sauce that elevates brilliant players to heights of strategic invention they could never attain alone, driven by their mutual urge to challenge the conventions of their times. Unsurprisingly, the game of Go has given rise to some fierce competition over the ages. From the lofty imperial courts of Edo-period Japan to the ultra-fast blitz rounds of crowded online servers, we bring you the five most spirited and influential pairs of rivals to ever throw down at the Go board.

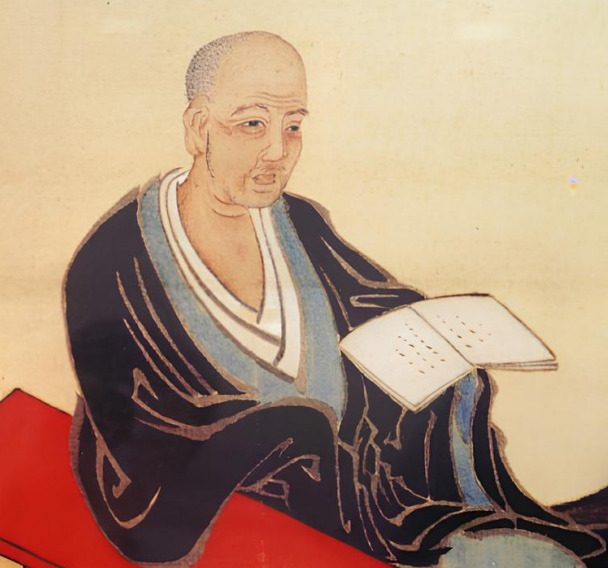

5. Honinbo Genjo (本因坊元丈) vs. Yasui Chitoku (安井知得)

Picture credit: https://note.com/curon154/n/n7b296c9c7a3c

If you happened to be passionate about the game of Go in the early 19th century, Japan was the place to be. Thanks to financial subsidies introduced by the Edo government for the benefit of talented Go players and their affiliated schools, the game underwent a period of cultural and technical transformation that would come to be known as the Golden Age of Go; and at the height of this transformative era stood Honinbo Genjo and Yasui Chitoku.

Genjo was born Miyashige Rakuzan (宮重楽山) in Edo in 1775 to a Samurai family with connections to the Shogunate. In 1798, he became heir to Honinbo Retsugen, of the Honinbo school, and changed his first name to Genjo. He ascended to the head of the Honinbo house in 1809.

Chitoku, born Nakano Isogoro (中野磯五郎) on Mishima Island in the Izu province in 1776, was the son of a fisherman. He moved to Edo at a young age and was adopted into the Yasui house, where his talent for Go quickly became apparent. In 1800, he was appointed heir and changed his first name to Chitoku,* and in 1814 was promoted to the highest rank of 8-dan as the 8th head of the Yasui house.

The two first played in 1788, when both were still in their early teens. Chitoku took Black (and the advantage) and won by resignation. The encounter marked the beginning of a lifelong kinship between the future-legends.

Genjo and Chitoku were two of the most equally-matched rivals in the history of Go: Of their 80-odd surviving game records, Chitoku won five more times than Genjo, but also took Black seven more times, making their lifetime results almost perfectly even.

Their rivalry was further enlivened by a few critical factors: both were almost the same age; both were promoted to 8-dan in the same year; both developed greatly contrasting styles – Genjo built thick, high positions to support his powerful attacking skills, while Chitoku took early territory and a restrained approach that minimized weaknesses for the opponent to exploit; but perhaps the most influencing factor of all was the friendship that blossomed between them early on, that grew out of deep, mutual respect.

Genjo and Yasui are today known as two of the Four Go Sages:* four legendary players of the Edo period widely recognized to be of Meijin level – the highest title claimed by the undisputed champion of the land – but who, for various historical reasons, did not become Meijin. In the case of Genjo and Yasui, their friendship was so great and their esteem for one another so profound, that they together chose to forgo the pursuit of the title, believing that it would be inevitably bestowed by the heavens upon the one truly deserving player. Their decision was all the more exceptional at a time when more ambitious players resorted to devious scheming to become Meijin, a position that conferred power, money, and prestige to its holder.

*Changing names throughout one’s life was a common practice for players of the time

*Along with Honinbo Shuwa and Inoue Genan

Featured: The Dame Myoshu (Beautiful Mistake) game, 1812

4. Ke Jie (柯洁) vs. Park Junghwan (박정환)

Photo credit: https://sports.news.nate.com/view/20191013n16771

These are exciting times for the game of Go, not in the least thanks to the passionate rivalry of Ke Jie and Park Junghwan, superstars of the computer age. Chinese-born Ke and Korean-born Junghwan turned professional at ages 10 and 13 respectively. After making a clean sweep of their respective national titles and breaking onto the international scene in spectacular fashion,* they became the second youngest players in history to reach the highest ranking of 9-dan at 17 years of age, beaten only by 16-year-old Korean female-prodigy Kim Eunji; Ke and Park took the world of Go by storm, and they took it fast.

But they play it fast, too.

If speed is king in the modern world, Go is no exception: Thanks to the vast, virtual training grounds offered by Go servers, ultra-fast games played with 10 to 30 seconds per move have become increasingly popular among professionals on the internet. These informal “Blitz” rounds may be directly responsible for the exponentially-increasing quality of play in official two-hour games in general, and in games that last into Byoyomi* time specifically. Ke and Park have so far played each other 33 times officially,* however, they have played each other many, many more times on the Chinese server Fox Weiqi under the pseudonyms “maker” for Park and “潜伏” for Ke – meaning “Lurking.” Ke estimates that he has played over 20,000 games online since he first learned Go at the age of six.

But other than a mutual interest in high-speed games, Ke and Park could not be more different players. Park has a solid, calculated style that relies on strategic openings and an exceptionally strong endgame: He’s a level-headed player who favours sure, incremental gains over brash risks. In an even match between the two, if no dramatic advantage has been seized by the beginning of the endgame, Park will usually win. Ke, conversely, is a dynamic player highly skilled at middle game fighting, who thrives on suspenseful liberty races (who captures whom first!) and chaotic, AI-inspired board configurations. He is known for his preference for White and holds a winning percentage playing it over twice as high compared to starting with Black, which has gained him the reputation of “world’s best player with White.” In Go, the player who takes White is awarded 6.5* extra points at the end of the game to compensate for the advantage gained by Black for playing first; This compensation is called Komi. While the consensus on the optimal number for Komi is still out, Ke seems to consider it large enough to provide a comfortable advantage, and so allows himself the laxity of playing more freely and aggressively when he takes White.

*2nd Bailing Cup for Ke and 16th Asian Games for Junghwan

*An overtime system that reverts to seconds per move once all the player’s time is used up

*Park leads 17 wins to 16

*The half point serves as tiebreaker

Featured: Final game of the 7th Chinese New Year Special Tournament Match, 2019

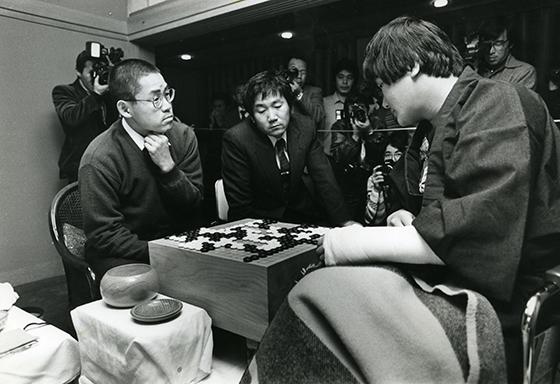

3. Kobayashi Koichi (小林 光一) vs. Cho Chikun (조치훈)

Photo credit: https://www.cyberoro.com/news/news_view.oro?num=523481

It is as if the two rising stars of the Kitani Dojo were predestined to become arch-rivals from the very beginning.

In March of 1965, 12-year-old Kobayashi Koichi – already a hailed regional champion – moved down to Tokyo from the mountains of Hokkaido to study at Kitani Minoru’s prestigious Go school. On his very first day of apprenticeship, he encountered a child with a toy pistol strapped to his waist running gleefully through the school hallways, and dismissed him as some neighbourhood fledgling. When he discovered that the 8-year-old Korean Cho Chikun had not only already been a student there for three years, but was in fact stronger than himself by a couple of stones, he was floored.

A 100-game match was promptly declared between the two in which the odds fluctuated violently: Consecutive winning streaks by each player forced the other to handicaps of up to four stones at a time.* In the end Cho won the match, and Kobayashi vowed revenge.

The desire to catch up with Cho served as a powerful incentive for Kobayashi to study, and his efforts proved successful in 1967, when he beat his rival to the rank of professional 1st-dan by a whole year. Decades later, Kobayashi is still widely considered to be the most studious player of his generation. In 1980, he casually admitted to Go researcher John Power that he had studied the complete games of 19th century Legend Honinbo Shusaku 10 times since 1965, meaning that he had played through the entire collection of 400-plus games every 18 months on average over that 15-year-period; Kobayashi once lamented to 6-dan Nakayama Noriyuki that the nail of his index finger, “the one fingernail I never had to cut in the old days,” was growing too fast, a telltale sign of his negligence!* Try to imagine how many hours a day one would have to spend placing Go stones on a board in order to wear away their fingernail…

The talented Cho was no slack either, but had trouble focusing on Go initially due to the stress he experienced from bullying and homesickness. When he finally committed himself in his teens, he vowed to not return home to Korea before becoming Meijin. In 1981, at the age of 25, he returned home for the first time in 18 years. He would go on to win the Meijin title five years in a row, and four more times again between 1996 and 2000. While perhaps lacking the sheer grinding power of his rival, Cho has been just as devoted to studying Go and has set himself the impossible task of mastering every aspect of the game: “My Go doesn’t have any particular pattern or style. My game consists of bringing everything together without using set patterns of play. This absence of style is my style. I try to match strength with strength, lightness with lightness. My ideal is to play in such a way that no one can tell who the player was.”

What makes Cho and Kobayashi’s rivalry truly unique is the way it permeated multiple facets of their lives: both climbed the promotional ladder at a similar rate and stood at the top of the Go world by their early 20s; both married older women, had happy marriages, had a son and a daughter, and tragically lost their wives to cancer; both have endured severe personal setbacks that impacted their level of play for years on end; and both have risen from their respective piles of rubble to reclaim world titles, in better shape than ever before.

*The more consecutive games you lose in a multi-game match, the more starting handicap you receive from the other player

*The traditional way to hold a Go stone is to clamp it against the tip of the index with the bottom of the middle finger

Featured: Fourth game of the 10th Meijin Title Match, 1985

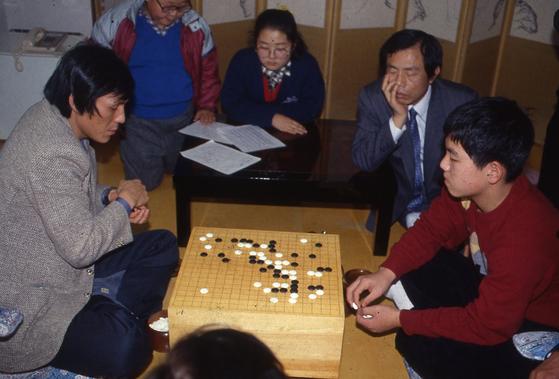

2. Cho Hun-hyun (조훈현) vs. Lee Chang-ho (이창호)

Photo credit: https://www.joongang.co.kr/article/25324626

Of the sparks of rivalry that may ignite between two worthy opponents, few match the intensity of those that fly when a disciple overtakes their master: repeatedly, in a series of maddening half-point victories.

In 1984, 31-year old Cho Hun-hyun held all the domestic titles and was fiercely taking on the top players in the world as the very first Korean 9-dan. By a stroke of fate, he was offered the chance to mentor the 9-year-old boy who had just placed first in the National Youth Championship and 3rd in the World Youth Championship. It was highly unusual for an active professional in their prime to take on a student, and besides, Hun-hyun was rather unimpressed with the young Lee Chang-ho: He thought the boy played well enough, but found him “nondescript and inarticulate,” showing no sign of genius and having trouble even to recall his own games on demand…. Nevertheless, Hun-hyun had an inexplicable feeling about the boy, and trusting his intuition, he accepted the mentorship.

Four years later, at the 28th Chaegowi Tournament, after besting all the other high-ranked players, 3-dan Chang-ho earned the opportunity to challenge his teacher for the title in a best-of-five match, the first title match to ever be played between teacher and student in the history of Korean Go. Hun-hyun defended his title, but not without Chang-ho snagging a win by half a point.

The win was written off by most as simply luck, but Hun-hyun knew better than anyone what his 14-year-old pupil was already achieving. Chang-ho had worked tirelessly, analyzing his master’s game records and playing patterns for years in order to identify his weakness and develop a winning strategy: The result was a slow, impenetrable style anchored in his own personality, that favoured secure, sober moves over his master’s nimble, strategically-active ones. To these “unspecial” moves, Chang-ho could apply his hyper-calculating ability to determine endgame boundaries with razor-sharp precision long before the endgame ever began, thereby allowing him to control the final score down to a half-point result. This calm, unwavering play coupled with his inscrutable demeanour at the Go board would quickly earn him the moniker of “Stone Buddha.”

Sure enough, it took only two more years for the young Stone Buddha to claim his first title from Hun-hyun, and by 1995 he had won them all. Towering over the Go world, Chang-ho would go on to claim a total of 20 half-point victories against his teacher, and overall 188 wins against 119 losses.

Despite both players’ drop in total world rankings over the past twenty years at the hands of consecutive generations of geniuses, Hun-hyun and Chang-ho have far from retreated into the shadows, and their achievements continue to reverberate across the professional Go world: Hun-hyun holds the record for most national titles won (160), while Chang-ho holds the records for most international titles won (21) and longest reigning world champion for an astonishing 15 years, held between the ages of 15 and 30 (by 30 he had lived half of his life as world champion!). And to top that off, both teacher and student hold the records for the highest and second-highest number of professional wins in history, respectively, at 1964 and 1922.

But the legacy of the pair has spread beyond the comparatively niche world of professional Go: On March 26, 2025, the previously-delayed and highly anticipated drama-biopic “The Match” (승부), based on their master-student rivalry, featuring Korean superstars Lee Byung-hun and Yoo Ah-in, was released theatrically in Korea to critical acclaim.

Featured: Third game of the 28th Choegowi Title Match, 1988

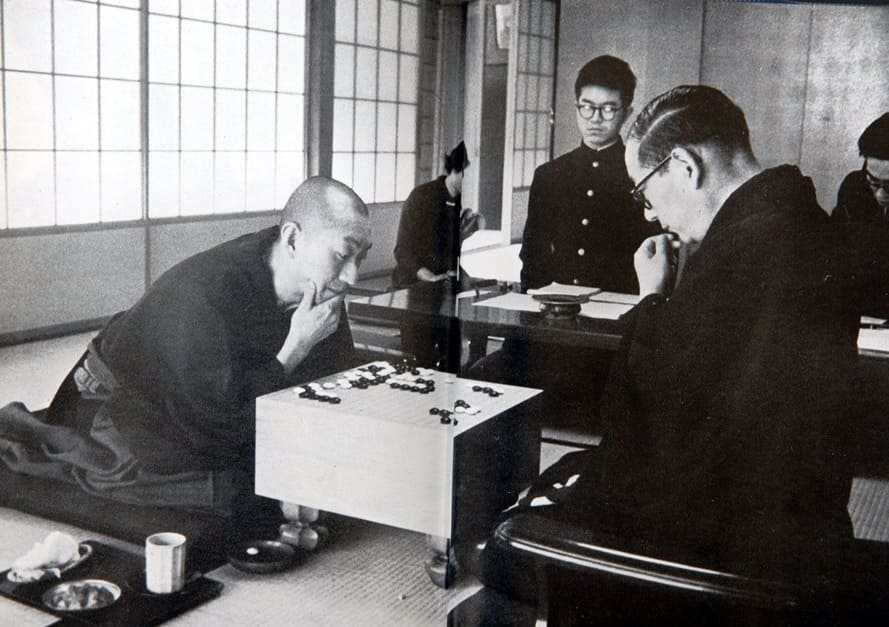

1. Go Seigen (吳清源) vs. Kitani Minoru (木谷実)

Photo credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kamakura_-_juban-go.png

There have been some truly awe-inspiring players since the advent of Go, some of them so divinely inventive that they have been elevated to the lofty status of sainthood. And yet, among the scores of objectively-great players that have made their mark on history, only a handful can lay claim to the supreme role of Pioneer of this unsolvable, ever-evolving game. Not only were Go Seigen and Kitani Minoru personally responsible for one of the most important evolutionary leaps in Go in the 20th century, but they happened to simply trigger this evolution in casual collaboration, as a serendipitous result of their endless curiosity sitting across from each other at the Go Board.

From the beginning, there was never much doubt about the individual greatness of neither Go nor Kitani.

Go, who was born in 1914 in the Chinese province of Fujian as Wu Qing-yuan, was already winning even games against visiting Japanese professionals at the age of 13. At a time when the best Chinese players could not possibly compete against the Japanese without a handicap, news of the young foreign prodigy spread like wildfire throughout the country that had been dominating the game for half a millennium. Heeding the invitation to study with the acclaimed Segoe Kensaku, Wu arrived in Japan in 1928 to a flamboyant national reception, immediately beat three professional players in a row and was awarded the rank of 3-dan professional under his newly-chosen name Go Seigen.

Japanese-bred Minoru was a young genius in his own right who had risen to the rank of 4-dan by the age of 18* and acquired the nickname “Kaidomaru” (monster kid) for beating 10 players in a row at the 1927 Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun Competition. Minoru would quickly prove to be the only player of Go’s generation who could evenly match him.

Their first game took place in 1929 at the Jiji Shimpo Competition, and although it would mark the start of a lifelong companionship, it was not exactly an auspicious encounter: Uncomfortable in his Japanese kimono and unable to kneel in the formal seiza position, the shaven-head, incongruous Go bowed shyly and played his first move on the centre point of the board.

In the game of Go, it is considered more advantageous to begin by occupying the corners first, then the sides, and finally the centre, given that the number of stones required to secure territory increases the farther away you move from the edges of the board. Quite logical then for this bold, unusual opening to surprise Kitani, but surprise quickly gave way to astonishment as his opponent began to mimic his every move symmetrically, a style known as “mirror Go.” Kitani complained incredulously to the organizers, but seeing as there was no existing rule against this type of play, it was allowed. Go later explained that he developed this strategy against Kitani because he was intimidated by the latter’s strength and believed that he needed to try something entirely different if he were to have any chance of winning. It was a sly but ultimately brilliant way to exploit White’s lack of Komi* by capitalizing on Black’s starting advantage from the very first stone. Go played this way for 63 moves before breaking symmetry, and while he gained a slight advantage, Kitani played a brilliant move and ended up winning the game by 3 points.

Despite the intensity of the encounter, or perhaps as a result of it, the ‘Mirror Game’ brought Go and Kitani together like long lost friends.

And then the friends started a revolution: Over the next five years, Go and Kitani explored novel corner, side, and centre openings that emphasized influence and fast development as a means of side-stepping the increasingly complex and stuffy traditional corner patterns and their excessive codification practices. In 1934, they published their exotic explorations in the Shin Fuseki-Ho (New Opening Revolution) to an explosive reaction. Given that the pair had already demonstrated the value of their new opening theory a year prior by finishing first and second respectively in the Japanese professional rating tournament, the book was hailed revolutionary and set off a craze of experimentation among both professionals and amateurs that produced even more original, bizarre, and brilliant openings; Go and Kitani, aged 20 and 25, had unintentionally redefined the framework of modern Go and ushered in the era of Shin Fuseki.

In 1939, Go bested Kitani 6 to 4 in the Kamakura Jubango, a 10-game match played at the Buddhist temples of Kamakura that became the most celebrated Jubango of the 20th century. Go went on to challenge the top players of his day repeatedly in 10-game matches. Of these, he lost a single match over the course of twenty years, during which time he completely dominated the professional Go world.

Kitani went on to establish his famous Dojo, notable for producing the crop of professionals that would dominate the Japanese and Korean Go scene from the mid 1950s through the late 1990s; His landmark victory against the last historic Meijin, Honinbo Shusai, marking the latter’s retirement, was immortalized in the sober style of Nobel-Prize-winning author Kawabata Yasunari, in his seminal 1954-novel “The Master of Go.”

Go and Kitani lived within walking distance from one another and remained close friends until Kitani’s untimely death in 1975. Go retired from professional play in 1983 and devoted himself entirely to promoting, writing about, learning, and teaching Go until his own death in 2014. He is widely regarded to have been the strongest player of the 20th century.

Go and Kitani, raging with talent and insatiable curiosity, carved out a new path for Go; and the ancient game will never be the same.

*This was considered exceptional at a time when 9-dan professionals were only a handful.

*Komi is a compensation of points to White for Black playing first. It was introduced in professional games in subsequent decades.

Featured: First encounter at the Jiji Shimpo Competition, 1929

❤️

<3 :))