Growing Gains: A Practical Guide to Improving off the Go Board

Introduction

There’s no question that Go is a profoundly interconnected game, wherein every move subtly or drastically affects every other. But this interconnection extends beyond the individual moves themselves: The core skills of Go are deeply interdependent, with mastery in one area often requiring a deep understanding and integration of the others. Most players who persevere at the game don’t fail to improve due to a lack of effort, they fail because their effort is scattered and inconsistent. One week is spent solving random problems, the next memorizing joseki, and yet the next grinding games online, all without a clear sense of how these activities relate to one another or how they address their actual weaknesses.

While slow, incremental gains are certainly achievable through scattered practice, the most meaningful improvement comes from integrating the core elements of the game into a structured, continual study routine. Only by doing so can one unlock the deeper levels of intuitive understanding of the invisible network of patterns that connects each and every stone—the metaphorical mycelium that runs through the Go board.

This article lays out a practical framework for building such a study practice: identifying the core skills that define Go strength, determining your level in relation to each of these skills, and translating the resulting insights into a sustainable routine that produces actual results.

The Core Skills of Go (and How to Train Them)

The most efficient way to improve at any complex discipline is to break it into discrete components that can be trained separately. Humans learn most effectively through this “divide and conquer” approach: our brains can only process so much information at the same time, yet they excel at integrating independently trained actions into a fluid, coordinated whole.

In the same way, a serious bodybuilder cannot rely solely on multi-purpose compound lifts to become stronger. They must also perform simpler movements that target specific muscle groups in isolation, repeated consistently over long periods, in order to achieve meaningful overall gains.

Go improvement follows the same logic. When each aspect of the game is trained independently and consistently, those skills reinforce one another over time and eventually combine into a level of play that is greater than the sum of its parts.

Let’s look at the major skills that collectively define strength in Go and how to train them.

Reading

Reading is the mental process of visualizing move sequences before they are physically played on the board. It is widely considered the most important skill in Go and often the deciding factor between two evenly matched players, as the player who can read more deeply and accurately under time pressure almost always prevails in a decisive fight. For this reason, fighting itself is largely a function of reading ability.

How to train

The fastest way to improve one’s reading is through life-and-death problems, also known as tsumego. These puzzles are solved by finding the precise sequences of moves required to either kill a group or secure its life. Top professionals are known to spend hours a day on tsumego, and many classic collections—some hundreds of years old – remain staples of serious study whose sheer ingenuity has elevated tsumego to a veritable art form.

Shape

Shapes are said to be efficient when stones are connected flexibly and occupy or protect vital points. Good shape is naturally strong and resistant to attack, while bad shape creates weaknesses that the opponent can exploit while expanding their own position.

Most losses in high-level Go are not caused by dramatic blunders, but by the quiet accumulation of inefficient moves that sap the vitality of stones and lead to heavy shapes, eyeless groups, and other positions that collapse under sustained pressure.

How to train

- Studying common shapes will help you internalize efficient patterns and integrate them naturally into your play.

- Tesuji collections are especially valuable, as they demonstrate how a single well-chosen shape move can create decisive tactical advantages both in fighting and life-and-death situations.

Strategy

Strategic skill is a refined sensibility to the areas of strategic relevance at every stage of the game. It’s the invaluable ability to perceive the board holistically, as a single, interconnected, interdependent ecosystem as opposed to scattered pockets of stones to be managed independently. Effective strategic play presupposes a deep understanding of the balance between influence and territory, a clear sense of direction, and acute positional judgement (see below). Strong strategists take the advantage by choosing where to develop, where to fight, and where to ignore with confidence.

How to train

- Learning and re-learning opening theory, as one progresses in skill.

- Analyzing whole-board positions through choose-the-right-move problem sets

- Reviewing one’s own games (high kyu +).

- Reviewing professional games (low dan +).

Endgame

Once the main territories on the board have been settled, the game enters its final stage, where players compete to secure the largest remaining moves before their opponent. Endgame skill requires precise counting to identify moves with the highest point value alongside moves that preserve the initiative, and to determine the correct order in which to play them. Games that appear conclusive in the late middle game are often decided in the endgame by only a handful of points, and players who approach this phase half-heartedly are often surprised at the final count to discover that what felt like a clear advantage has quietly slipped through their fingers.

Because of the numerical precision involved, endgame study becomes especially relevant at the upper kyu-level and above, where games are decided by increasingly narrow margins rather than large tactical swings.

How to train

- Learning the fundamentals of endgame counting and working through dedicated problem sets to improve speed and accuracy.

- Studying the different types of endgame sente and gote moves, and practicing common sequences to develop a reliable sense of timing and move order.

Positional Judgement

Positional judgement is the ability to accurately evaluate which side is ahead and by how much, in order to formulate a sound strategic plan or recalibrate an existing one: whether the position calls for risk or restraint; when to attack or defend; and when to complicate or simplify. Rather than relying on vague impressions or emotional momentum – as amateurs often do – players with strong positional judgement base their choices on an objective assessment of the board’s overall balance.

At the highest levels, this skill becomes almost instantaneous. Top professionals can assess complex positions within seconds, accurately estimating the score to within a couple of points and adjusting their plans accordingly.

How to train

- Practicing full-board score estimation exercises.

- Deliberate in-game counting: Developing the habit of frequently assessing the overall score during play, even roughly, will significantly improve your counting speed and accuracy, and consequently your strategic decision-making at all stages of the game.

Determining Your Level (and Why it Matters)

If you have only recently started playing Go, it is generally safe to assume that you fall somewhere in the 30–20 kyu range, and you may proceed to build a study plan centered around the very basics.

However, if you have been playing for some time and are unsure of your current strength, determining your level is an important step to studying effectively as it will help you focus on the skills that will yield the greatest improvement. Given that study material in Go is highly level-dependent, problems that are too easy will offer minimal growth, while material that is too advanced can be discouraging or simply misunderstood. A reasonably accurate sense of your level will allow you to choose problems, books, and exercises that sit just beyond your current ability, where learning becomes the most efficient.

Diagnostics

To begin, the team at Go Magic has put together an excellent diagnostic test designed to determine your playing strength. The test is available in multiple formats, ranging from an express version (≈ 10 minutes) to a full version (≈ 40 minutes), depending on how thoroughly you wish to evaluate yourself.

The results are generally accurate within 1–2 kyu and provide a strong starting point for identifying your current level. Furthermore, the tool will suggest areas of study focus based on your results.

Why One Type of Measurement Isn’t Enough

In Go, overall strength is the result of multiple, independent yet overlapping skills that often develop unevenly: reading, strategy, shape, endgame, and positional judgement. As a result, rank can fluctuate significantly depending on personal strengths, matchup and context. It is not unusual for a 11-kyu player with exceptional reading to defeat an otherwise stronger 8-kyu player, nor for a 1-dan player with average positional judgement to lose consistently against a strategically sharp 1-kyu player.

Because of this variability, no single tool can capture a player’s true strength across their full skillset. For a more reliable estimate, therefore, it is best to use multiple methods and then average the results.

Additional Ways to Measure Your Strength

a. Online Play – Human and AI Opponents

Playing rated games online, against both human opponents and bots, remains one of the most practical ways to gauge your strength. Over a sufficiently large sample of games, your rank will stabilize around your true level. Be mindful, however, that ranks vary between servers and that short-term results can fluctuate. Sensei’s Library provides a worldwide rank comparison chart that equates ranks across different Go servers and international organizations. While useful as a reference, the survey is somewhat outdated and should be treated as an approximate guide rather than a precise conversion.

b. Baduk.org Full-Board Test

This test, compiled by 3-dan professional Alexander Dinerstein consists of 20 full-board problems designed to assess overall playing strength. It offers problems that evaluate full-board judgement as well as localized tactical skill.

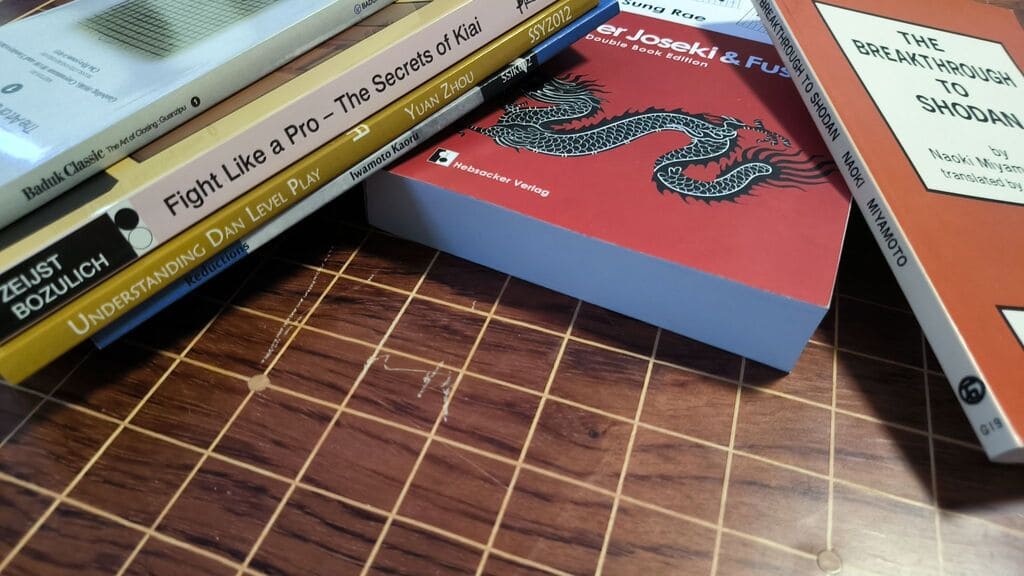

c. Miyamoto Naoki – Test Your Go Strength

This classic problem collection from 1975 offers a methodical, structured self-assessment. The book contains 50 multiple-choice problems divided into three sections:

- 20 opening (fuseki) problems

- 20 middlegame problems

- 10 endgame problems

Each answer is assigned a score based on its quality, and by tallying your total, you arrive at an estimated rank. While not a highly precise measurement tool, the book rewards careful analysis and provides insight into your strengths and weaknesses across different phases of the game. You can find this book at gobooks.com

d. How Deep Is Your Go?

This tool analyzes your games in SGF format and returns a rating and rank on the OGS scale. Accuracy improves with the number of games submitted. When uploading multiple files, ensure that the player name is consistent so that the program correctly identifies your moves with Black or White.

Skill Table

The skill table presented below outlines how different core abilities typically develop across different ranks. Keep in mind that these descriptions are broad averages, and individual players will often deviate from these patterns depending on their natural inclinations and areas of focus. As such, your own profile may show strengths above your nominal rank in some areas and weaknesses below it in others. It is meant to be used not as a set of labels, but as a diagnostic lens – another tool to help you understand where your study time will be most effective.

| Level/Skill | Reading/Fighting | Strategy | Shape Efficiency | Endgame | Positional Judgement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30k to 20k | Reads one or two moves ahead at most and recognizes simple instances of atari and capturing. | Possesses no sense of strategy beyond occupying empty areas on the board; plays locally and responds automatically to immediate threats. | Applies basic connecting and cutting principles semi-arbitrarily, without a clear sense of how stones work together. | Does not count points; plays endgame moves instinctively with little to no sense of value or initiative. | Evaluates positions as alive or dead, with no meaningful score estimation or point-range awareness barring a visibly striking imbalance of territory. |

| 20k to 10k | Can read 3–4 move sequences and solve basic life-and-death situations on the go; fights to capture and kill rather than to profit and develop. | Identifies large points and increasingly weighs options before playing; forms simple strategic goals that extend beyond local move sequences. | Makes use of common, solid shapes and avoids obvious bad ones; stones serve the uni-dimensional purpose of building living groups. | Identifies obvious endgame moves and sente plays without meaningful coordination; counting is approximate and rarely decisive. | Makes rough evaluations based on perceived advantage and overall feeling within a very broad range (30+ points). |

| 10k to 1k | Reads 5–7 moves ahead in straightforward positions and maintains accuracy in complex middle-game situations; approach to fighting shifts from killing to gaining profit and expanding influence. | Considers the whole board position when formulating plans but lacks the tactical precision to execute them correctly; capable of adapting an initial strategy as the game develops. | Occupies and protects vital points semi-efficiently; stones are sacrificed in service of light shape and better leveraged for attacking and developing territory. | Distinguishes different types of sente and gote and prioritizes sequences that keep the initiative; counts with reasonable accuracy to determine move order. | Can determine which side is ahead with moderate accuracy, typically within a range of 15–20 points; lacks the consistency to use positional judgement reliably for guiding long-term strategy. |

| 1 dan + | Reads 10+ moves ahead comfortably while managing multiple branch variations; selects fights deliberately, avoids unnecessary complications and punishes overplay with confidence. | Consistently chooses the appropriate direction of play; times attacks, invasions, and reductions with high accuracy; coordinates local play with global board position to optimize long-term strategy with every move; | Intuitively creates flexible, resilient shapes in complex positions; each move serves multiple functions across attack (probing etc), defense (settling etc), and development; | Counts accurately under pressure while comparing point value against move initiative; executes endgame sequences in optimal order. | Assesses positions quickly and frequently and can estimate the score within a 5–10 point margin; bases strategic goals consistently on objective evaluation. |

Building a Training Routine (and Sticking to it)

Once you understand the core skills that make up Go strength and have determined your current level, the next step is to synthesize that information into a simple, sustainable study routine. The goal is not to study everything at once, but to study the most important things consistently.

Identify Your Primary Focus

Start by selecting one core skill as your main area of improvement, and one or two secondary skills depending on your available study time and level of motivation. Your primary focus should be your weakest area relative to your rank, or the one most likely to yield immediate gains (often reading or whole-board strategy for kyu players, and endgame or positional judgement for stronger players). Secondary skills can still be practiced regularly for balanced development, but the fastest overall progress will come from concentrating your efforts on a single primary skill.

Study by Availability

Your routine should fit your schedule, not compete with it:

- 5–10 minutes: Life-and-death problems, quick reading drills, or single-move shape recognition exercises.

- 10–20 minutes: Endgame flashcards or middle-game/whole-board exercises.

- 20–40 minutes: Opening theory study, structured problem sets, or positional evaluation exercises.

- 45+ minutes: Review of personal or professional games, in-depth analyses, or other desired studying.

Remember that short, frequent sessions are far more effective cognitively than occasional, extended study marathons. A modest, well-defined routine followed consistently will outperform ambitious plans that are difficult to sustain. In Go, as in all cerebral disciplines, steady, directed effort compounds slowly but surely over time into concrete results.

Review and Adjust Periodically

Every few weeks, reassess your level using the same diagnostic tools provided above and adjust your focus area(s) accordingly. As one weakness improves, another will naturally emerge as part of the growth process. An effective study practice is never static, but evolves organically alongside your game.

Additional Tips and Resources

- Delay AI game analysis until you reach dan-level play. Relying on AI too early – without fully understanding the reasoning behind its moves – can encourage shallow pattern imitation and overconfidence, rather than fostering careful reading and sound judgement.

- If you want to improve faster, work with a teacher. A strong teacher can identify blind spots, refine your focus, rekindle your motivation, and accelerate progress dramatically. Go Magic offers several experienced teachers who would be happy to work with you.

- Use tools that support consistency. Phone apps are especially useful for maintaining a study routine on the Go. The Go Magic Skill Tree in particular helps you plan your study by skill, track progress, and ensure that each session contributes to long-term improvement. For a broader overview of problem-solving apps and tools, see here.

Further Reading and Practice Resources

- A deep dive into improving your reading ability

- Optimized Endgame Flashcards for fast, focused practice

- An excellent curated guide to Go books from beginner through 1-dan

Conclusion

While the point of this article is to emphasize the value of structured study, it’s important to remember that Go is first and foremost a game, and the most powerful driver of improvement in any game is simply to play it. No amount of off-board work can replace the experience of real positions, real decisions, and real mistakes made in live play. Especially in the early stages (roughly up to 20-15 kyu), what matters most is to play as much as possible. As the Go proverb reminds us: “Lose your first 100 games as fast as possible.”

At Go Magic, we recommend spending about 60% of your Go time playing, and the remaining 40% studying. Playing provides essential experiential context and exposes areas of weakness; studying addresses those weaknesses with focussed, specialized tools. Together, they form a positive feedback loop in which each deepens the effectiveness of the other.

Just as important to keep in mind is that improvement thrives on enjoyment. Learning research consistently shows that the brain absorbs information much more effectively when engagement is playful and driven by curiosity. This is one reason beginners – and children in particular – tend to improve so quickly. So whether you’re playing or studying, enjoy the process. And don’t worry about winning or losing: Victory is not required to improve – it’s the unassuming, inevitable result of it.

All I can say is that from reading the contents, I knew this were to be a great read. It came right on time since I’ve started pondering on how I should build up an effective study/practice plan.

Thanks for reading! I hope it helps you build the study routine that is perfect for you. And remember to have fun :))

*this was going to be a great read*

I’ll try this, thanks!

Cheers!

Thank you for the exceptional article. I think that having in one place a brief overview of the larger skills conceptualized throughout Go theory history was really necessary. I enjoyed the sober discussion how they blend to determine overall rank and why ranks hold inherent variability due to this. Also, the surveying of strength tests was a nice touch.

Glad you enjoyed! Thanks for reading 🙂