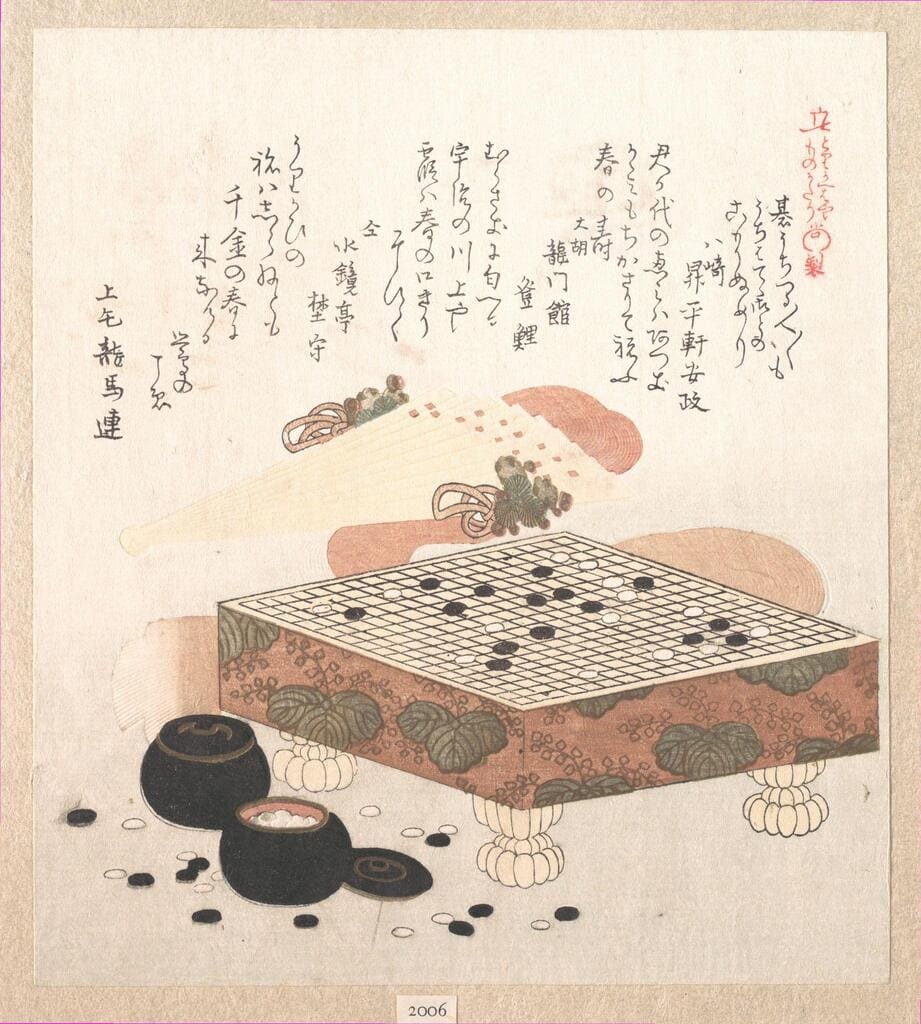

Exploring the Intricacies of Go Through Its Global Rule Sets

Did you know that there is a plethora of Go rule sets around the world? I’m sure you’ve heard of some of them: Chinese rules, Japanese rules, and maybe even AGA rules–but could you actually identify the difference between each rule set? And how they’d affect the outcome of a game?

In this article, I’m going to review six of the most popular rule sets and how they differ from each other.

I’m also going to review territory scoring versus area scoring, cover a few unique situations, and then review a few examples from professional games–where the chosen rule set changed the outcome of the game.

If you’re new to Go or need a refresher on the rules, check out How to Play Go article.

Territory vs. Area Scoring

Before we dive into the different rule sets, I want to quickly review the difference between territory and area scoring–as knowing the difference between the two is fundamental to understanding how the rule sets function. Check out Go Magic’s video and chart below.

| Territory Scoring | Area Scoring |

|---|---|

| Commonly known as Japanese counting | Often called Chinese counting |

| Score is counted by empty points within a player’s territory | Every stone on the board counts towards the overall score. |

| At the end of the game, prisoners are placed in the opponent’s territory, subtracting from their score | Captured stones are placed back into the bowls and not kept as prisoners |

| Each player’s overall score is the sum of their territory and prisoners | Neutral points/dame count towards the overall score, as that each stone is counted to calculate the score |

| Traditionally, empty intersections in seki are not counted |

The Rule Sets

The following section compares the rule sets of:

- AGA

- Japanese

- Chinese

- Korean

- Ing’s SST

- New Zealand

AGA Rules

The AGA rules are the rules used by the American Go Association. This rule set is best characterized by attempting to make any game played under AGA scoring have the same result—whether the players use territory scoring or area scoring.

In order to end the game, when a player passes, they give their opponent a “pass stone” which becomes a prisoner. White must pass last.

Scoring: Area or Territory minus prisoners (Resulting winner is always the same in either case due to AGA provisions.)

Komi: 7.5

Handicap Score Adjustment: When area counting is in effect, White receives an additional point of compensation for each black handicap stone after the first. (Otherwise black would receive an additional point for each handicap stone.)

Self-Capture: Illegal

Super-Ko: Repetitions are explicitly forbidden.

Ending the Game: Either two or three consecutive passes, with White being the last to pass. Opponent receives one prisoner for each pass.

Dame Filling During Stone Removal: No

Stone Removal: Dead stones mutually agreed upon.

Japanese Rules

Japanese rules are best characterized by its territory style scoring. In fact, Japanese rules are one of the most commonly taught and used by casual players in local play.

Scoring: Territory minus prisoners

Komi: 6.5

Handicap Score Adjustment: None

Self-Capture: Illegal

Super-Ko: Legal, however, one side must be willing to break the loop, otherwise the game ends in no-result.

Ending the Game: Two passes

Dame Filling During Stone Removal: Yes, placements must be agreed upon by both players.

Stone Removal: Group life and death status is determined according to Japanese rules and removed accordingly.

Chinese Rules

Chinese rules are best characterized by their use of area scoring, where every single stone on the ending board is counted towards the final score. The Chinese Weiqi Association uses the area scoring method.

Scoring: Area

Komi: 7.5

Handicap Score Adjustment: White receives an additional point of compensation for each black handicap stone.

Self-Capture: Illegal

Super-Ko: Repetitions are explicitly forbidden.

Ending the Game: Two passes

Dame Filling During Stone Removal: No

Stone Removal Phase: Dead stones mutually agreed upon.

Korean Rules

Korean rules are the rules adopted by the Korean Baduk Association. Overall, Korean rules have clear rules for super-ko situations–all of which end in a draw/no-result.

Scoring: Territory minus prisoners

Komi: 6.5

Handicap Score Adjustment: None.

Self-Capture: Illegal

Super-Ko: Legal, however, one side must be willing to break the loop, otherwise the game ends in no-result.

Ending the Game: Two passes

Dame Filling During Stone Removal: Yes, placements must be agreed upon by both players.

Stone Removal Phase: Subject to special Korean stone removal rules

Ing’s SST Rules

Ing Chang-Ki, a Go philanthropist and promoter of the game, created his own rules–called the Ing Rules. The Ing Rules are perhaps the most complicated rules covered in this article, especially for amateur play. Both players must have exactly 180 stones in order to play. Players count by filling in their own territory with stones.

Scoring: Area

Komi: 8

Handicap Score Adjustment: White receives an additional point of compensation for each black Handicap stone.

Self-Capture: Yes

Super-Ko: Forces avoidance of repetition through special SST Ko Rule

Ending the Game: Two passes

Dame Filling During Stone Removal: Yes, alternating placements.

Stone Removal Phase: Dead stones mutually agreed upon.

New Zealand Rules

These are the rules commonly used by the New Zealand Go society. The most interesting part of this rule set is that a player can “suicide” or self-capture their own stones.

Scoring: Area

Komi: 7

Handicap Score Adjustment: None

Self-Capture: Yes

Super-Ko: Repetitions are forbidden

Ending the Game: Two passes.

Dame Filling During Stone Removal: No

Stone Removal Phase: Dead stones mutually agreed upon.

Interesting Situations

The following are unique situations and rules that come up during a game of Go.

Super Ko and ING Special Ko

The term super ko refers to a rule created by Ikeda Toshio, a former amateur go player whose numerous rule proposals have largely been adopted over the years, where he expanded the concept of a single ko repetition to whole board repetition including triple kos, quadruple kos, eternal kos, and cyclic kos. With the creation of the super ko rule he sought to eliminate drawn games.

Eternal Life

Eternal life is a term that refers to a state of a game of go where a certain position of the board repeats. The super ko and Ing special ko rules help prevent eternal life from occurring.

Eternal life refers to the following sequence below:

Check out the following professional game between Uchida Shuhei and O Meien where eternal life occurs at move 100.

A video detailing the Eternal Life situation

Triple Ko

The triple ko is a unique situation in Go where there are three active kos being played on the board. Under Korean and Japanese rules, triple kos are allowed, but one side must be willing to break the loop–otherwise the game ends in a draw or no result. Check out this real life example of a triple ko in a 1975 game between Cho Chikun and Kato Masao starting at move 145.

Bent-Four in Corner

Unlike the typical bent-four, the bent-four in the corner is usually considered dead. Under Japanese rules, unless the ko is played out, the shape is considered dead.

Example of a bent four in the corner

A video detailing the Bent-Four in Corner situation

Self-Capture

Self-capture or suicide is banned under most rule sets, but is legal under New Zealand rules and Ing Rules. Playing a self-capture can be advantageous in the event of a ko fight. See the diagram below.

In this diagram from Sensei’s Library after white self-captures at 1, black must come back and play at 1, otherwise white can kill the group. In this example, it’s clear to see how self-capture rules could matter towards the outcome of a game.

Self-capture can also change the winner of a capturing race. Black is losing this capturing race–but if black can play at A it creates a seki. See for yourself the value of self-capturing in this situation.

For enthusiasts eager to delve deeper into the captivating world of Go, our website features an exclusive course The Magic of Go — Complete Edition. This comprehensive course meticulously explores peculiar ko fights, extraordinary tesujis, rules disputes and all the scenarios mentioned in this text.

Unique Situations by Rule Set

| Rules | Triple-ko, Eternal life | Seki points | Bent-four |

|---|---|---|---|

| AGA | Repeats forbidden | Yes | Play it out |

| Japanese | Break loop or draw | No | Dead |

| Chinese | Repeats banned; possible draw | Yes | Play it out |

| Korean | Draw/no-result | No | Dead |

| Ing’s SST Rules | Ko requires elsewhere play | Yes | Play it out |

| New Zealand | Repeats forbidden | Yes | Play it out |

Real Examples of Rule Discrepancies

While all the different sets of rules seek to determine the true winner of the game, there are instances where different rule sets determine a different winner. Here are a few examples where confusion about the rules affected the outcome of the match.

Takagawa Kaku vs. Go Seigen (1959)

Another fascinating example from Fairbairn’s book was the 1959 game between Go Seigen and Takagawa Kaku.

In the game, Go believed he did not have to play a fill-in move in the center, as that his opponent did not have enough ko threats. The current Nihon Ki-in rules of the time required Go to play the move. Go protested that because he was not a Nihon Ki-in member and this wasn’t a Nihon Ki-in event, the rules shouldn’t be enforced here. The judge ruled that a fill-in was required by the current Nihon Ki-in rules, and so Go lost by half a point.

Kobayashi Koichi vs. Ma Xiochun (1993)

This game was the second in a three game match between Kobayashi and Ma during the 6th Japan–China Meijin playoff. Ma had won against Kobayashi during the previous year’s Meijin playoff and was currently leading 1-0 in the 1993 match.

According to the 70th issue of Go World, during the game, Kobayashi led by a slim margin and had already calculated his victory. Dame points and a seemingly inconsequential ko were the only uncertain points left on the board. Kobayashi became upset when Ma battled incessantly over the ko–feeling it was disrespectful and pointless. Ma pointed out that because they were playing under Chinese rules the ko and dame were in fact very important to the score. In fact, Kobayashi, still befuddled from the contentious ko exchange, accidentally played successive moves–a cause for forfeit under Chinese rules–but Ma, knowing he had fairly lost the contest decided not to ask the referee to enforce the forfeit and accepted his loss.

Check out the game below. The sequence in question is from move 245-278.

Huang Yizhong vs. Kim Kang-keun (2004)

Rule sets matter, and in 2004, Huang Yizhong of China and Kim Kang-keun of Korea discovered just how much they matter.

During the infamous game, detailed by Sensei’s Library, Huang accidentally put a prisoner in his opponent’s bowl. Under Chinese rules, this wouldn’t have mattered–but under Japanese rules this mattered greatly. In fact, the game ended up being decided by half a point.

The accident caused great confusion among the players and both players realized there was something wrong with the score. Huang, calculating the score by Chinese rules, discovered there was in fact a missing stone. The sequence in question is presumably after move 188, which would have been Huang’s fifth prisoner.

The problem in question became whether Huang or Kim deserved the win. Kim felt that he had made his decisions based upon the agreed-upon game state, and Huang felt he was the rightful winner.

In the end, media backlash towards Kim shamed the player into forfeiting the win. This was a preliminary match before the main competition.

Chen Yaoye vs. Iyama Yuta (2015)

In the final game of the 4th Super Meijin tournament in Xi’an China, Japanese fans were ecstatic when they thought Iyama had won by half a point. That excitement quickly turned to confusion when Chen was declared the victor. This was due to the fact that the international match was being played under Chinese rules and the seki on the right side counted towards Chen’s score. (Seki points are not counted under Japanese rules).

See the game below and check out the final losing position for Iyama.

It’s important to understand the intricacies of your country or region’s rule set before you start the game. As exemplified by the previous examples, even professional players often make mistakes while navigating different rule sets. While the game of Go is praised for its universal appeal and simplicity–there are still complicated details amongst the different rulesets that can change the outcome of a game. How does the rule set in your country or region influence your approach to the game of Go, and which rules do you prefer? Share your thoughts and experiences in the comments below.

Leave a comment