On Honinbo Shusaku

Mukashi, Mukashi…

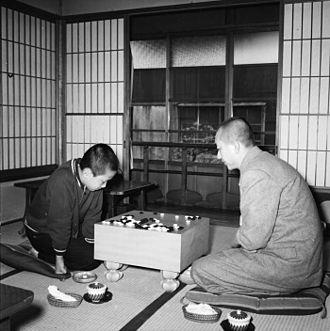

You, Kishi, are seated in a fine tatami room. You are full of food and drink and feeling fine. The locals have wined and dined you well, and as you can well guess, they now wish to ply you. With what, you can also guess. You are Ito Showa, a well-respected Go Kishi affiliated with the Honinbo house. And yes, here he comes, the young little genius these common countrysiders imagine to be a real diamond in the rough. Play him a game, they say. You’ll see right away. He’s something else; a creature of heaven. How uncouth. You’ve seen too many of these kind to expect anything beyond a paltry offering. Every fish thinks they’re big until they leave their river and jump into the sea. The thought alone raises the bile in you and darkens your mood.

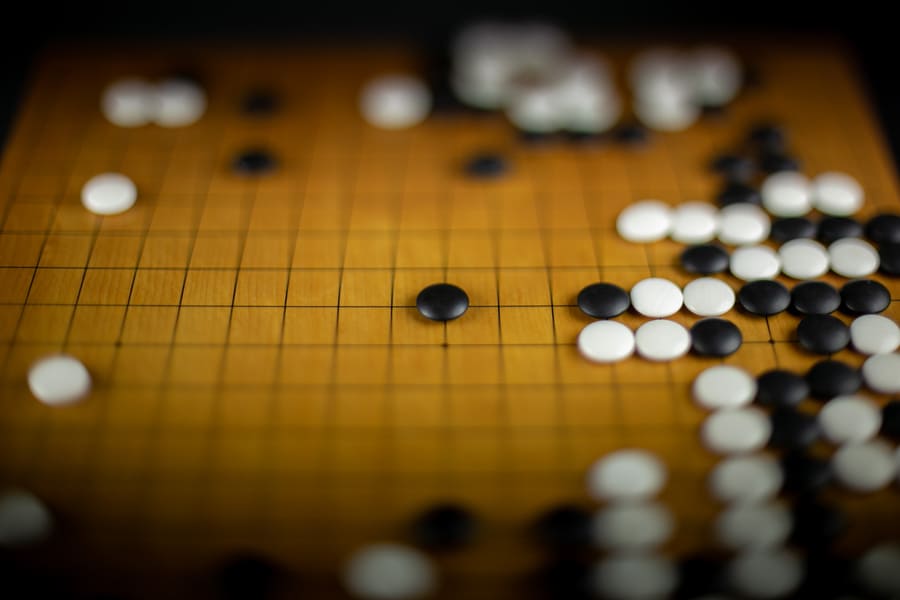

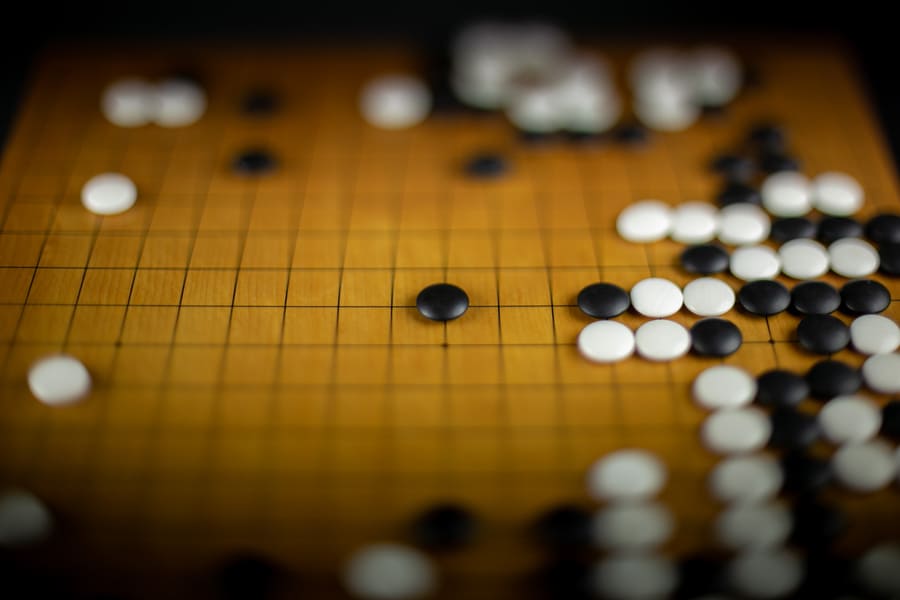

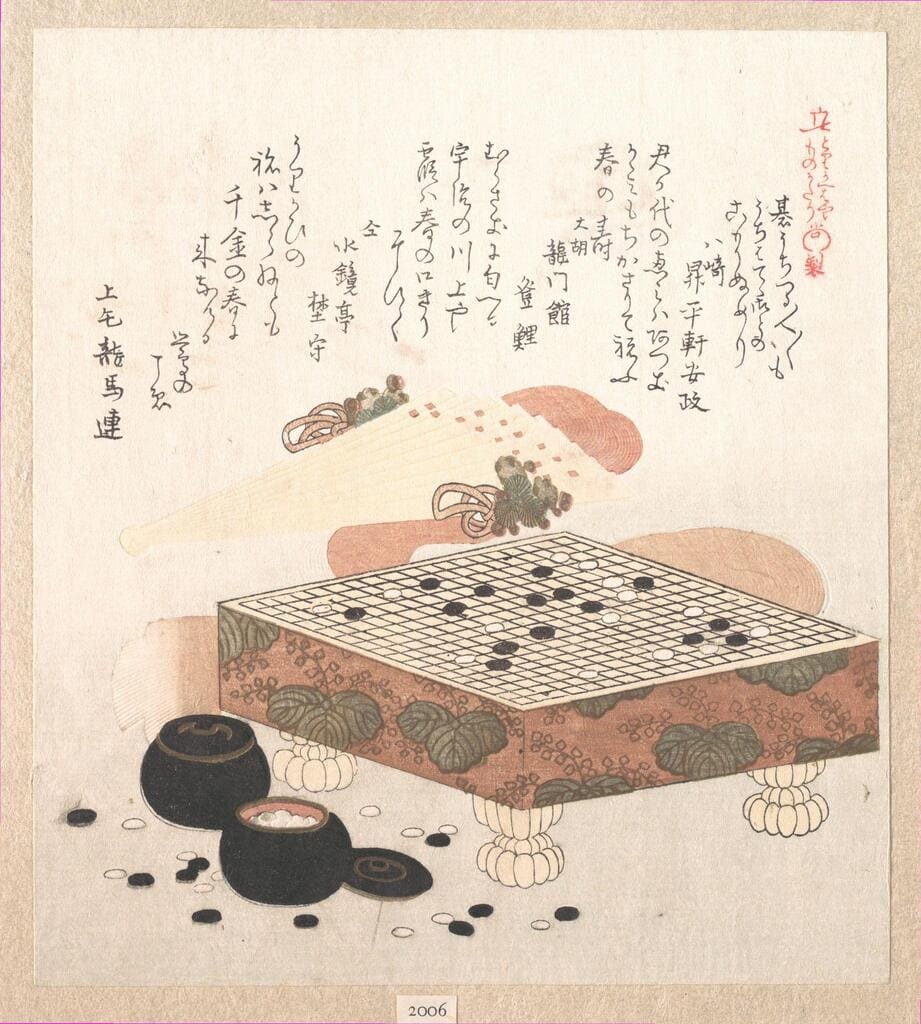

Unthinking, you lash out and insult the boy. But all he does is sit calmly across the Go board from you, waiting. Something inside your gut twists. All of a sudden, you feel a tremble in your hand as you reach to uncap the Go bowls. But you’re not that old. The boy’s manners aren’t that odd. Well, what is it then? Perhaps, as all the rest of us have come to know only after you, you too have come to know that history speaks in moments like that. Not from the pages of a book, but from a person’s eyes and the way they hold yours; from their lips it pours, and from their hands it is born.

Stories like this from the life of Honinbo Shusaku (1829 – 1862) emphasize how dramatic his life was. But what of his Go? Certainly, Shusaku’s Go is full of beautiful forms and powerful moves, but many a modern player wouldn’t call Shusaku’s famous style “dramatic” in the way we think of the word. And there are many modern players that could contest Shusaku for being “the best to ever touch the stones,” but for my money, I would argue that no player has the dramatis persona such as that which has followed after Honinbo Shusaku, past his death, through his ghost, and into our lives.

An Opening Assessment

Shusaku was born in the Edo era (roughly 1600 to 1868) in a small fishing village near Hiroshima on the island of Innoshima and was quickly recognized as being a Go prodigy.

The story related above (embellished, mind you) was a real event. Ito Showa actually met boy Shusaku, did insult him, and was subsequently forced to eat his words after playing a game against him. (Later in life Ito Showa apologized to Shusaku for his poor behavior at their first meeting, but Shusaku politely declined the apology, telling his dear tutor and mentor that he was energized by the remark and may not have played as well as he did without it.) Soon after passing this test against the venerable Ito Showa, Shusaku was quickly whisked off to Edo (present day Tokyo) and apprenticed to the Honinbo Go House to which Ito Showa was affiliated.

There is something of a rags to riches element to this tale. The Honinbo House was one of four Go houses under the supervision of the Jisha Bugyo, or “The Commissioner for Shrines and Temples.” The Honinbo was the most successful and the most prestigious, but all four were directly funded by the government, receiving a healthy stipend of rice and money so that their members could focus directly on the study and play of the art of Go. The pinnacle of this highly developed Go Culture was playing in the annual Castle Games, a competition of sorts held in front of the Shogun himself (if he chose to attend)! If you were widely recognized as the best Go Kishi of the day, you could even be appointed Meijin, the personal teacher of the Shogun himself.

Something of an unimaginably wonderful setup for any of us modern Go dreamers, the Go houses were a semi-hereditary quasi-school-family scheme which was quite common for many different forms of art in Edo Japan; Go was recognized by the shogun as being more than just a game, but a function of strategy applicable to war as well as settling domestic affairs. This put the game of Go as well as the professionals who played it on a special pedestal within the very strict ordering of feudal Edo society. Normally it would have been impossible for a fisherman’s son such as Shusaku to move up into the aristocrat ranks — and certainly no fisherman’s son from Hiroshima ever before dared dream of the honor of prostrating himself and performing a long loved art in front of the Shogun himself, and certainly not in Edo Castle.

Shusaku would be given such a chance, not just once, but nineteen times. Keep this in mind, dear Kishi as we proceed: there can be no understating just how meteoric Shusaku’s rise was.

This small opening volley will serve as a solid framing of the context. That said, herein I will not take a long and detailed look at the details of Shusaku’s life per se; there are many places where such information can be found and I highly recommend that every serious student of Go buy John Power’s incredible book: “INVINCIBLE THE GAMES OF SHUSAKU.” Such beautiful histories of Shusaku already exist and in fact, quite a bit of Shusaku’s life story is something of common knowledge, espoused on the internet and passed around at any old gathering of Go players. This leaves me in a land where I could only tread over already trampled ground. Therefore, herein I’d like to examine what are the elements and factors of Shusaku (player and Go) that pertain to our modern Go era, why he isn’t remembered for what you might think, and why you should absolutely still study him.

Rethinking Shusaku

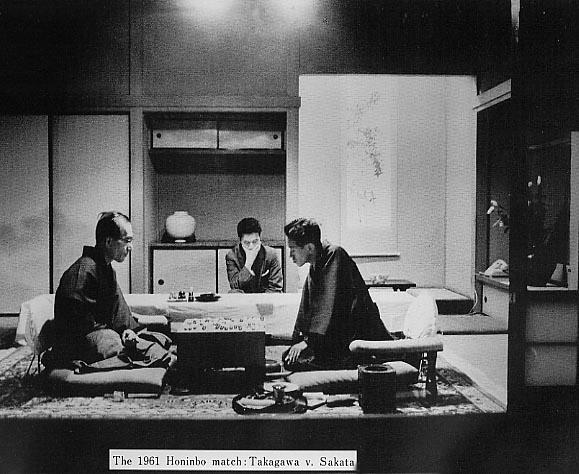

To begin, what elements of Shusaku are unique that make him required reading and study for the serious amateur (or the even more serious professional)? Is it his being a savant discovered at a young age? Certainly not. He was not unique in that regard. Shusaku himself discovered and helped raise several young geniuses and our modern and slightly pre-modern era are rife with them. In fact, our modern era almost insists upon them. These days, if you aren’t a pro before fifteen, well… But in Shusaku’s time the ideas on peak ability were different. You weren’t thought to be in your prime until you were in your late thirties or early forties; only then, could you play your “mature style.” Go skill was thought to be something like the aging of a fine whiskey: you needed the right ingredients to start, but it would only be truly great with time. Nowadays we pinpoint the peak of any player’s skill in the mid-twenties or early thirties. This precipitous change in attitude led off the modern era when Rin Kaiho took the Meijin title from Sakata Eio. Sakata was in his prime by the old calculations at 45 years, Rin Kaiho the prodigy still unripe at 23.

So, if not his age or his touted genius, what about Shusaku’s style? We all know well the famous Shusaku Style Opening and the even more famous Shusaku Kosumi; but it must be stated upfront, my fellow Kishi: Shusaku’s style was not unique. This might come as a shock to some people who imagine that Shusaku brought new kinds of style to the Go board. He did not. His style was highly regular for the time in the fashion of the Honinbo House: steady and secure, with a focus on opening theory. His teacher, Honinbo Shuwa, was a proponent of this style and some argue that he played it better than Shusaku.

Shusaku’s style of Go has been compared poetically to a beautiful flowing river, harmonious in appearance, raging depths underneath. And while Shusaku’s Go is undeniably beautiful and refined, there is also no denying that it is not unique or original in its composition. He did not even invent the pattern which bears his name. What he did do was to take the pattern and experiment with it endlessly, as well as to divorce the famous kosumi from the pattern, often playing it even when he held white later in his life.

This could be summarized as Shusaku having a solid and beautiful style based on deep reading and excellent positional judgment. Compare this to Takemiya Masaki’s “Cosmic Go,” Cho Chikun’s extreme territorial style, or the innovative risks of players such as Fujisawa Shuko and Kajiwara Takeo, and Shusaku starts to look a little pallid.

Ok. Forget style then. Was Shusaku a great innovator of moves? Again. Sorry. No, not really. He toys with the star stone a bit in his youth but gives up on it until much later in his life, where he toys with it again without any real curiosity. He doesn’t break the mold or reform his generation’s understanding of Go Theory. Go Seigen and Kitani Minoru come much later as the first real revolutionaries and are followed by many others such as Nie Wei Ping and Cho Hun-hyun. This invites the question: if placed in our era, how would Shusaku stand up?

Shusaku on Modern Footing

The first thing we must remember is that in the Edo era when Shusaku lived, Go was played without komi of any kind. In this context, AI thinks highly of Shusaku. But with Komi? Many of Shusaku’s wins would be erased with a 6.5 tithe to white, to say little of the 7.5 in the Chinese rules. Another aspect of Shusaku’s Go that we must consider is time limits. Shusaku had none. Go in his era was played at the pace of the players and many games went on for several days. This would be an unthinkable boon for modern players and forces us to put many of the modern players on a slightly higher rise compared to their Edo era counterparts for being able to play brilliant Go under time pressure. We must also ask ourselves at what age are we taking Shusaku?

Shall we take him young — at say, fifteen — and transport him to the modern era to learn under the tutelage of AI Sensei and the modern opening theory? That seems unfair. We would be removing the context in which Shusaku grew to play “his” Go, which is the Go we want to see. We want the fully formed genius, and we want to see how that genius will respond to the new will of Go. Let’s take him at twenty-seven. He must play with komi and a time limit. Let’s watch the sparks fly. Genius is genius, of course, but it’s hard to imagine how he would compare to players like Go Seigen or any of the modern Japanese, Chinese, or Korean players. Personally, I imagine the heavy fighting style of the Korean players would be difficult for a player like Shusaku who only ever competed within the Japanese system. (Of course, at Shusaku’s time, the rest of the Go world was highly underdeveloped. No Chinese or Korean professional during the Edo era could even hope to compare to any of the Japanese. It was not an exaggeration but a fact to say that during the Edo era the best Japanese player was the best in the world.)

Rebuilding Shusaku

By now all this might sound intimidating. What could it possibly be that still grabs us about Shusaku? If not his style or his genius, then what? Well, the answer is: story, my good Kishi. He sticks around in our hearts and minds as something larger than the miniature of life he lived; this special aspect of his is what makes him an eternal presence on the Go boards of our minds. There is a reason Hikaru No Go uses Shusaku as a backdrop for the Go playing ghost, Sai. Shusaku’s story is rich and moving. He came from a small fishing village and made his way to the top of the Go world! And while many Go players in Shusaku’s era committed much intrigue, (see Honinbo Jowa and Gennan Inseki) Shusaku was famously a good-natured man his entire life. Humble and self-effacing even in his most amazing moments, Shusaku never let his genius go to his head. Even when he earned the right to play his teacher, Honinbo Shuwa, on even terms, Shusaku refused to ever take white, a sign of deep respect. Shusaku won all nineteen of his castle games and was considered almost INVINCIBLE when he held black, but never claimed such a title or was known to brag about his victories. Perhaps — as I have argued herein — Shusaku was so strong in what is an unflashy way, but this, too, was in keeping with the style of the man. It is often said the Go board reflects who you are; in Shusaku this was certainly the case.

Let us then call Shusaku the greatest instance of an easy to love hero. He is easy to identify with, and easy to root for. We want to be him. Every beginning Kishi imagines themselves as having some kind of spark in them that will be found and nurtured and recognized as something great; and all of us Kishi imagine that we have the potential still hidden in us long after we find that we don’t quite have the time or energy to dedicate to Go that we would like. Shusaku allows us to live out this dream vicariously: no more fishing for us, onwards to the great bustling city of Edo! Personable, loveable, and inspirational. Serene surfaces, hidden rapids, dramatic backdrops. Who among us doesn’t enjoy at least imagining ourselves in Shusaku’s shoes? He came from poverty and anonymity and played Go in front of the Shogun. His greatest rival was an Edo playboy by the name of Ota Yuzo, whom he crushed in a thirty-game match. He defeated the strongest amateur of all time — who was a samurai no less — too. He married Jowa’s daughter and even that old man couldn’t give Shusaku two stones. He made Gennan Inseki’s ears turn red in frustration and he died of a fever he acquired from caring for the other Honinbo students who had come down with a foreign sickness. Truly, Shusaku’s was a life fully lived, even if only for three decades and change. It is a story worthy of being told, admired, cherished, and told again.

Shusaku, Invincible After All

And what of Shusaku’s Go, then? What mark has it left? What should we take with us and why, oh why, should we study him seriously? The first remark I must make is a throat clearing: Shusaku was an extraordinarily strong player. He may not prefer complications or large-scale fighting, but when forced into such situations by his opponents, he soon swamps them and shows how powerful his reading is. We could say that Shusaku’s style belies his strength. Or, if we wanted to don the cowl of Honinbo, say that a one point win is still a win. But how does this wolf in sheep’s clothing come to be the one we must study above all others? Well, as related above, Shusaku had a Go style poetically called a peaceful river with hidden rapids in its depths. We can extrapolate this to mean that Shusaku’s moves are easy to understand and have a dangerous aspect to them if the opponent misplays. The study of such a style will be rewarding throughout your growth as a Go Kishi and it is this source of endless self renewal that invites players of all ages and of any strength to seriously consider the games of Shusaku.

If you are a kyu player, Shusaku will teach you shapes and fuseki strategy and how to secure your territory. If, as a kyu player, you mimic Shusaku’s style, you will find that you lose as many games as you win — it’s not a magic pill — but you will also find that your losing margins will shrink. Your games will no longer end in implosions (or, at the very least, there will be less of them). As you work your way up the ranks and get into the amateur dans you will find the depth of Shusaku’s moves begin to pop out at you. You’ll be able to see beneath the serene surface and absorb the tricks and pitfalls Shusaku is placing about the board. Consult some commentaries of his games and you’ll begin to realize there is an overwhelming pressure that builds up in the middle game following the peaceful opening; you’ll begin to feel how Shusaku’s opponents felt: How am I supposed to win against this? What is this overwhelming wave? There are lessons unique for each of us waiting in the games of Shusaku, no matter how far along on your Go journey you are. No other player has served such a role.

Take for example the beautiful style of Takemiya Masaki mentioned before: “Cosmic Go.” This is not a style that is easy to play or easy to explain. Any amateur of the kyu grade who tries it will most certainly feel frustration. This isn’t to say that the style isn’t accessible in any way, only that if you’re trying to teach Go and show beautiful and powerful Go that your students could grow from, Cosmic Go might not be the best place to start. The same could be said for the more exciting styles of Fujisawa Shuko and Kajiwara Takeo: fascinating and thrilling, but not the best place to start to learn how to play and understand Go. Indeed, for many professionals teaching, Shusaku serves as the golden standard to jump from, for amateurs and professionals alike. And this brings us to Shusaku’s effect on modern Go.

Previously, I stated that Shusaku was not a major innovator on the Go board. He had his moments like the famous Ear Reddening Move and his nineteen castle game wins, but overall? Solid and steady as it goes. But! Who were the real innovators I mentioned? Go Seigen and Kitani Minoru. Both have a connection to Shusaku. Go Seigen trained himself up to professional 3 dan level on the collected game records of Shusaku when he was growing up in China. (More proof that Shusaku’s games are the best tutor anyone could ask for, including a genius.)

Kitani Minoru also used Shusaku as the basis for his famous rock-solid style later in life. Go Seigen himself also switched back to using the Shusaku style in his later years when he held black (usually with a bit more dynamism, but still, the Shusaku effect is noticeable). We could even say there is a sort of hereditary feeling in the Shusaku style of Go that permeated the entire world.

Stay Calm, and Shusaku on

Shusaku’s story lingers and his Go still shines. Other stars come and go, but Shusaku’s refuses to fade. He remains fresh in our minds as a personable story, and he remains relevant on the Go board because no other player has approached the level of clean, pure, and simple Go like he has. If not the “best to ever touch the stones,” Shusaku does earn the title of the “purest to ever touch the stones.” His Go reflects this.

In closing, I encourage every Kishi, no matter your level, to review Shusaku’s games and read the commentaries on them. Many professionals who have won major titles have said that reviewing classic collections of games (Shuwa’s, Shusaku’s, and Shuei’s, to name a few of the most common) have revitalized their Go. Among these classic masters, Shusaku is the most accessible. And to us, when we feel stuck in a cycle of loss and loss and — hell! More loss! Well: take up Shusaku. Let’s sit across the board and hear a story as the stones come dancing across the 361 lines that compose the music of heaven.

About the Author

Matthew McKee is a member of the Go Magic team and a 4-dan player residing in Japan. A passionate Go enthusiast, he possesses extensive knowledge of Japanese Go history. Professionally, he is a college-educated archaeologist and writer, with two published novels to his credit: Keeping The Stars Awake and Flicker.

Matthew’s courses on our platform:

Leave a comment