Go Strategy and Tactics: How to Maximize Your Win Rate at Every Step of the Game

Introduction

“Strategy without tactics is the slowest route to victory. Tactics without strategy is the noise before defeat.” — unknown

One of the most compelling aspects of Go compared to other games is its endless capacity for strategic invention. It’s what captivates players of all levels and drives the most ambitious and creative among them to pursue ever-greater mastery. Yet to become too fixated on Go’s underlying strategic framework and neglect its dynamic tactical arsenal would be a grave mistake. This is, after all, a game of war, where victory depends equally on both types of weaponry: Strategy and Tactics. Strategy is the pen that sketches out the vision of victory, imbuing our play with direction and purpose; Tactics are the blade that carves this vision into the board, stone by stone, with surgical precision. The pen may be mightier than the sword, but only about half of the time.

If your recent discovery of Go has left you exhilarated and eager to master its fundamentals in order to move on to the deeper, war-general levels of scheming, you’ve come to the right place. In this guide, we’ll explore the game comprehensively through its three main stages: the Opening, the Middle Game, and the Endgame. By learning the principles covered in each stage and applying the strategies and tactics that arise from them, you’ll quickly find yourself playing several stones stronger.

Since this article assumes a basic familiarity with the rules and mechanics of Go (placing & capturing stones, eyes, life and death, counting, rankings etc), if you have no prior knowledge of the game and find yourself led here by nothing other than a piqued interest, you’re in luck: Our in-house team of Sensei Extraordinaires has prepared a series of brilliant, interactive courses that will teach you everything you need to start playing and winning your very first games. Furthermore, these courses introduce foundational principles necessary to understand some of the more technical concepts discussed below. You can also explore our Beginner’s Guide for some practical tips as you embark on your newfound Go journey.

Are you ready? Let’s GO.

Setting the Pace from Start to Finish

The dramatic arc of a game of Go unfolds over three main acts: the Opening, the Middle Game, and the Endgame. Each stage manifests its own tensions and demands its own resolutions: Where do I even begin? How should I expand? When should I attack? What should I defend? How do I turn advantage into points?

Succeeding in this evolving struggle depends on seizing an early advantage and maintaining it until the very end – from the strategic groundwork of the opening, through the tactical clashes of the middle game, to the closing maneuvers of the endgame. The player who sets the pace wins the race.

Helpful Link: Three Stages of the Game

1. Opening

With 361 legal opening moves on a full 19×19 board, deciding where to place your first stone can feel paralyzing. Even limiting yourself to one quadrant of the board (accounting for symmetry), there are still 100 possibilities to choose from. So, how do you choose?

Thankfully, due to theoretical and practical constraints, 99.9% of all Go games begin with fewer than 10 distinct opening moves. Even better news for beginners: You only really need to consider three main points: the 3-3, 3-4, and 4-4 points; More adventurous players might also explore the 3-5 and 4-5 points. Given the extensive literature devoted to each of these moves we won’t delve into their specifics in this article. Suffice it to say that each offers its own unique blend of influence and territory.

Influence & Territory

The first great balancing act every Go player must perform is to choose between influence and territory – between the potential of acquiring space and the certainty of owning it. Territory is tangible: secure, surrounded points that can already be counted; Influence is subtler: the anticipation of future territory radiating from a strong formation of stones.

In the early stages of the game, influence typically outweighs territory. The open board favours dynamic formations that serve as launch pads for large-scale attacks rather than static positions that enclose territory prematurely. As the game develops, the interconnectedness of the influence-territory relationship is elucidated: Abstract influence takes concrete shape as increasingly defined frameworks crystallize into solid territory.

Beginners to this complex and subtle relationship tend to err at either extreme: They surround territory too early, clinging to corners and sides while neglecting the open space of the board; Or they play too loosely for influence, developing hollow positions with no real territorial substance. It takes a fair amount of skill to know when to emphasize one over the other, but real mastery to cultivate influence organically and allow one’s stones to blossom into full-blown, far-reaching territory in their own time, in the living garden of Go.

Helpful Link: Territory and Influence

Whole-Board Thinking

We can only begin to understand influence and territory properly once we start viewing the board as a single, interconnected whole.

When our vision is restricted to a single area, we play myopically: We chase short-term gains, respond automatically to the opponent, and treat local exchanges as isolated events. To think globally is to operate with the awareness that every move indirectly affects all position: that developing along the edge foresees an expanding framework; that defending a weak group builds strength for a future attack; that a local fight can drastically alter the balance of power across the entire board.

But even after grasping the idea of whole-board thinking from a theoretical stance, it’s perfectly normal to struggle on a practical level with coordinating several areas of play at once, let alone the entire board. The surest way to develop this mindset and ingrain it into your play is to make a habit of stepping back before every move to assess the full board situation. By applying this simple directive, you will hone the ability to sense which areas matter most and gradually attune yourself to the flow of the game: the way moves follow naturally from the current state of the board rather than artificially force an isolated advantage.

As your whole-board perception improves, so will your command of the powerful tactic of tenuki: ignoring the opponent’s local move in favor of a larger opportunity elsewhere. The strength of a well-timed tenuki stems from the simple fact that the biggest move on the board is not always where the last stone was played. By cultivating a holistic awareness of the game, we can repeatedly steal the initiative (sente) from our opponent and redirect the play toward areas of greater potential, which is often the key to winning.

But if keeping the initiative is so crucial in Go, can we simply ignore everything our opponent does and play wherever we please?

Helpful Links:

The Joy of Ignoring Your Opponent

Urgency

The guiding principle is this: Urgent before big.

Not all moves carry equal weight on the Go board. Among the many strategic instincts you’ll develop as you improve, one of the most vital will be recognizing what must be played now. It helps to think of these moves as the ones you need to play before the ones you want to play.

Urgent (need) moves stabilize your groups by securing a base, connecting to strength, or running to the center – and threaten your opponent’s weak groups in the same way. Big (want) moves develop influence and expand your frameworks while limiting your opponent’s potential. But what counts as “big” is not always clear. A quiet move that stores up strength in the long run often proves more effective than a flashy, short-lived attack. Conversely, a move that’s perfectly fine for a later stage of the game may be disastrously small in the opening, losing you the initiative by allowing the opponent to claim the largest point on the board.

Ultimately, improving at Go has much to do with developing a sense of timing and tuning into the rhythm and flow of the stones (whole-board thinking). Knowing when to defend, when to strike, and when to expand is a mark of strategic maturity. And the coolest moves, of course, are those that manage to do everything at once.

Helpful Links:

Efficiency

Embedded into the very fabric of the game is a deceptively simple goal that elegantly dictates all of your decisions: securing the most territory with the fewest possible stones. Consider how many points you can secure with the same number of stones in different areas of the board:

- Corners require the smallest number of stones to secure territory.

- Sides require more stones than corners but fewer than the center.

- Center territory demands dramatically more stones to secure the same number of points.

This basic principle is the reason the game starts in the corners and extends sideways and into the center. Your stones work harder for you in the corner than anywhere else on the board, making it the key type of area in the very first stages of the opening.

But the principle of efficiency extends far beyond claiming territory points. The hallmark of a strong move is the number of layered strategic and tactical objectives it can accomplish simultaneously: A peep that forces your opponent into a heavy shape while strengthening your own; a sacrifice that creates endgame value while making eyes for a weak group; an extension that secures territory, builds influence and suppresses the opponent’s framework all at the same time.

In essence, efficiency is the discipline that silently governs all great Go. While it is certainly a sensibility that develops over time, the simple awareness that every move should serve a deeper purpose beyond its surface value can bring us that much closer to winning, because fortune favours the player that makes each stone count.

Helpful Link: Move Efficiency

A Practical Guide to the Opening

Grasping the aforementioned concepts intellectually is merely the first step on the road to the ever-profound, integrated type of understanding we are continuously aiming to reach as Go players. As such, trying to implement these rather abstract ideas into our own play can feel a little bit like navigating a bustling city with a world atlas: not nearly specific enough. Thankfully, the essence of these elusive concepts has been distilled from centuries of professional play into a simple set of guidelines to follow at every turn of the opening to help you find the next best move:

- Take as many empty corners as you can: They’re the most efficient territory on the table and the easiest to expand from. The more corners you have the better.

- Seal off your corners and approach your opponent’s ones: Secure what you have already laid claim to and then disrupt their safety.

- Take mutually interesting points: These are areas that expand both yours and your opponent’s positions.

- Take individually interesting points: These are expansion areas that are only interesting for one side.

- Play neutral points: Take the empty areas that remain on the board after the strategically relevant ones have all been claimed.

Helpful link: Key Priorities in Go Opening — The Core Principles of an Elegant Fuseki

Finding Your Style: Exploring Strategies

“When you form your strategy, know the strengths and weaknesses of your plan.” – Sun Tzu, The Art of War

Most professional players experiment with many openings throughout their careers in order to discover their own style and deepen their understanding of opening strategy in the process. Japanese Grandmaster Kato Masao explains: “My method is to concentrate on one Fuseki (opening) pattern for a long period of time. Thus, however much of a dullard I may be, I can feel confident that I have carried out more research on the pattern in question than my opponent. This confidence is what enables me to do well with my favourite Fuseki patterns. Discovering one’s favourite Fuseki, the Fuseki that best suits one’s temperament, is the surest way to improve at the opening.”

In this spirit of exploration, here are some well-established openings that cover different strategies along the influence-territory spectrum, which may help you find the approach that best suits your own style. While these openings are most often used by Black, they can easily be adapted for White with minor adjustments to account for Black’s initiative:

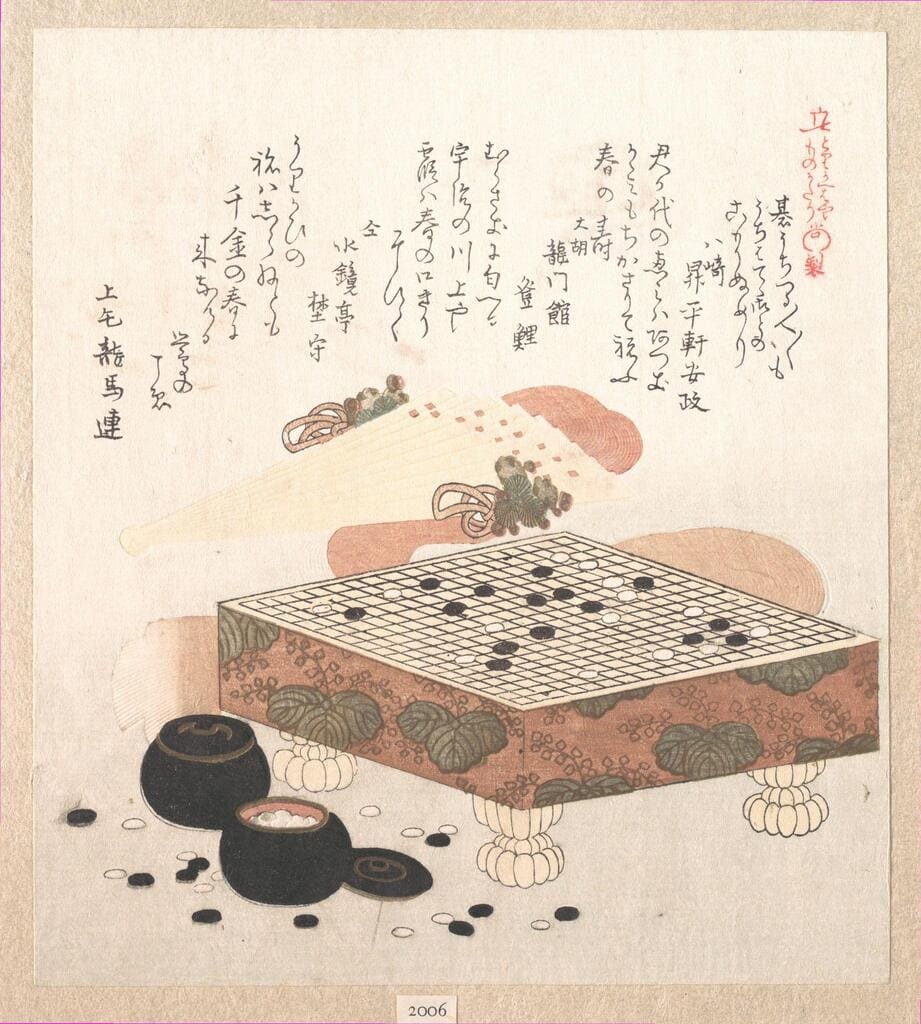

Shusaku Opening: Edo period genius Honinbo Shusaku is one of three players in the history of Japanese Go to have gained the title of “Sage” for their incomparable mastery of the game in their respective time periods. While the rotating 3-4 points had been played long before his time, it was Shusaku who developed them into a formalized opening strategy and used it to such effect that it became eponymous with his name. The pattern emerged as the preferred opening for Black in the time of Shusaku and remained so until the introduction of Komi in the 1930s. Today, it is regarded as the foundation of modern opening theory.

Honinbo Shusaku vs. Ito Showa at the annual Castle Games, 1859

After the first three moves, you may wonder why White would barge into Black’s top corner with move 4 instead of calmly taking the remaining empty corner, as per our opening guidelines. The reason is that a corner enclosure with a stone on the opposite side (move 3) was considered so valuable in the pre-komi period that it was thought better for White to approach in this manner to prevent it. Black 7 is the famous Shusaku diagonal, a relatively slow but extremely powerful move that envisions a solid win by restricting White’s scope of action toward the center.

Chinese Opening: This opening was first pioneered by amateur Chinese players in the 1950s. It wasn’t until the early 1960s, when 9-dan master Chen Zude used it extensively in the Japan-China Go exchange matches to great success, that the pattern caught the wider attention of the professional Go world.

Chen Zude vs. Sakata Eio at the Japan-China Go Exchange Games, 1973

Black plays 1, 3, and 5. Rather than enclose the bottom right corner for immediate profit, he aims bigger by developing a large framework that White will be forced to invade. By attacking this White invasion, Black hopes to create outer strength that will allow him to gain elsewhere on the board. The high-Chinese variant, wherein Black plays at the point immediately to the left of move 5, is an even more influence-oriented option than the low-Chinese (regular) opening.

Sanrensei: The first documented use of the “Three Stars in a Row” opening was in 1933 by Japanese master-educator Kitani Minoru, who helped establish it as one of the defining openings of the Shin Fuseki (Opening Revolution) era. While the Sanrensei is less commonly seen in modern professional play given the diverse ways for White to neutralise large-scale frameworks at high level play, it remains extremely popular with amateur players, who have a harder time invading and reducing efficiently. A notable exception is Japanese Go superstar Takemiya Masaki, who developed a highly expansive playing style in the 70s based on the Sanrensei that came to be known as “Cosmic Go,” with which he dominated his peers for decades.

Takemiya Masaki vs. Cho Chikun at the 21st Japanese Meijin tournament, 1996

Black occupies three star points on any same side of the board for maximum outer influence. Similar to the Chinese opening, The Sanrensei aims at a large framework that will invite an invasion by White, which Black will attack severely using his acquired thickness.

Tengen: Opening the game in the center point of the board is an audacious and somewhat reckless approach on behalf of Black, who is essentially challenging White to a large-scale fight from the very start. This opening is rarely used in professional play, not for being inherently inferior, but because its variations are significantly more complex and difficult to analyze. In other words, proceed with caution: This move demands deep reading and superior positional judgment.

An Younggil vs. Ryu Chaehyeong at the 10th Korean Fresh Best 10, 2003

Tengen is less about making early territory in the middle of the board (inefficient) and more about establishing a central anchor point towards which all future positions may converge: Securing this point will both support Black’s developing frameworks and endangered running groups and limit and chase White similarly, with the additional advantage that his Tengen stone will serve as a ladder breaker for all four corners at once.

Mirror Go: This is the practice of responding to the opponent’s move with its symmetrical counterpart on the opposite side of the board, thus “mirroring” it through the point reflection of the Tengen. The most famous example of Mirror Go is the first encounter between legendary rivals Go Seigen and Kitani Minoru in 1929, when Go opened on the Tengen (removing the only unique point) and mirrored Kitani for 64 moves, to the shock and criticism of those present.

Go Seigen vs. Kitani Minoru at the Jiji Shimpo Competition, 1929

The reasoning behind this type of otherwise passive play is that a mirrored sequence is of inherently equal value to the original, and therefore allows the mirroring player to avoid commitment while keeping the position balanced. In this manner, they can patiently assess the opponent’s moves for as long as they wish and only deviate from this strategy to take advantage of a move they judge as inferior.

Artificial Intelligence: AlphaGo’s landslide victory in 2016 over the world’s top player ushered in a new era for the game Go. Modern AI programs such as KataGo and Leela operate with a type of whole-board logic so alien to human intuition that they have overturned centuries of accumulated wisdom, while at the same time reaffirming some of the game’s deepest principles. And although the AI style is impossible to emulate without exceptional fighting strength and flawless calculating, professionals have been quick to adapt: By 2020, top players had integrated AI study into their daily training and allowed it to drastically reshape their openings and corner pattern repertoires. Today, AI analysis is an integral part of professional training and AI play is the dominating style in tournament games. Its influence continues to both refine and redefine our understanding of the game.

Katago playing itself in a rated game, 2025

The efficiency of corner territory has been emphatically validated by AI’s systematic 3-3 invasions early in the game. Conversely, it has a habit of responding to urgent threats by ignoring them altogether (tenuki), valuing sente above all else. The sheer calculating precision of AI enables it to maximize its probability of winning by tiny margins, as opposed to the human tendency of pursuing large territorial gains.

Helpful Link: Opening Classics

A Word on Joseki

Joseki are established corner sequences that have been developed, tested and refined over centuries of play. They represent the optimal patterns for approaching and defending a corner and yield a locally balanced result for both players.

As a beginner, you may have been advised (or pressured into the idea) that learning joseki is essential to improving your play. While joseki are indeed valuable, learning them through rote memorization is a misguided and counter-productive approach that can actually hinder your progress. A joseki is never “correct” in isolation – it must be understood in the context of the entire board; An excellent local result may be disastrous when the global position is taken into account. For this reason, studying joseki is a lot more nuanced than it appears to beginners, and ultimately not that beneficial to them. An old Go proverb astutely captures the dichotomy of memorizing versus understanding: “Learn joseki and lose two stones; Study joseki and gain four stones.” At this stage of your learning, rather than attempting to memorize complicated sequences, it’s far more useful to understand the ideas behind a few key patterns. Learn a maximum of two or three simple joseki thoroughly while paying attention to each move and why it works: the intentions behind it, the shapes it creates, and the influence it exerts. This conceptual understanding will serve you far better than simply remembering isolated sequences.

In any case, rest assured that a comprehensive knowledge of joseki is not at all necessary for beginners and arguably not even for strong amateurs. A solid grasp of the opening principles and the ability to think holistically at all stages of the game will together provide a much stronger foundation and prepare you to integrate joseki naturally into your play, as your understanding of the game gradually deepens.

Helpful links:

What Is Joseki and Why Learn Them

Finding the Right Joseki at the Right Time

2. Middle Game

Once opening frameworks have been established, conflicts quickly erupt over contested areas of the board, and the Middle Game begins. It is here that strategic vision and tactical judgement converge into actual warfare. Success in this stage hinges on your ability to bolster defenses, exploit weaknesses, and anticipate favorable outcomes through the skillful shaping of your stones, all while flexibly adapting to your opponent’s moves.

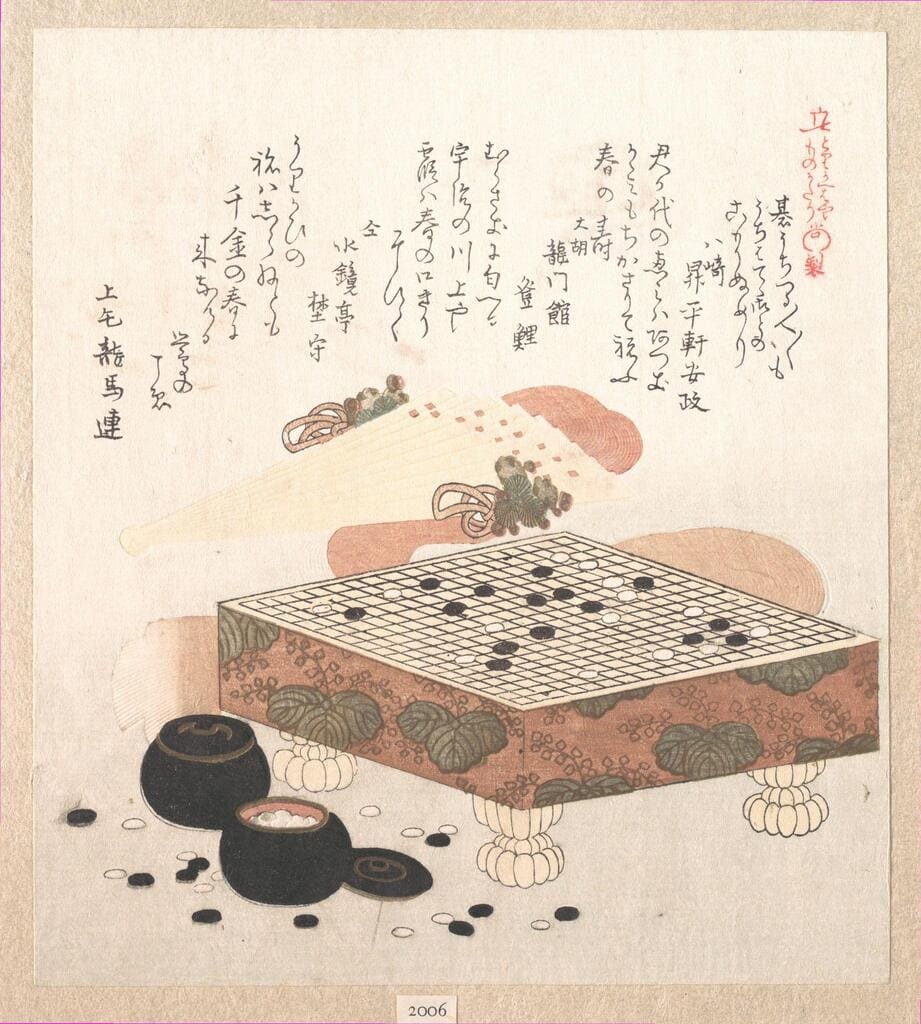

Reading

To read in Go is to visualize sequences of moves before they are physically played out on the board. It is the process of repeatedly asking oneself “If I play here, how will my opponent respond?” until the optimal line of play has been determined over all other variations.

Reading is considered to be the single most decisive skill in Go, and while estimates differ on how closely a player’s reading capacity correlates to their actual rank, there’s no doubt whatsoever that superior reading translates directly into superior play at all stages and all levels of the game. In other words, we can study as much theory and pore through as many Go manuals as we wish, but ultimately, our ability to strategize and tactically execute these strategies – our actual level of play – can only improve as fast as the depth, precision and speed of our reading ability.

It’s no surprise then that the very best Go players in the world can read out invisible lines of stones faster than most people can read out printed lines of words. Japanese 9-dan Sakata Eio, the famed “Razor,” once stated that he could “see thirty moves at a glance,” and top professionals will frequently analyze branches of 100+ moves each before deciding on an important play. As a beginner though, learning to read just two or three moves ahead with clarity can provide a decisive advantage.

A good starting point to improve at reading is to tackle its most basic form: ladders. Given that failing to read them out is one of the most common beginner mistakes, mastering them will immediately see you winning a lot more games. From there, you can practice reading nets and counting liberties in short capturing races. Read slowly and carefully, visualizing every move until you have determined the local result with absolute certainty. Reread as necessary. Like a muscle, the ability will grow stronger with use and you will soon find yourself confidently dominating local fights.

Helpful Links:

Reading Is Power! Where and How to Solve Go Problems

Reading Is Power: Improving Your Reading Ability in the Game of Go

Fighting

When stones come in contact in an area of the board that neither side can afford to cede, fighting is inevitable. This is where players’ reading skills, tactical knowledge, and nerves are all put to the test.

In these altercations, the upper hand is gained not through reckless aggression, but by using one’s formations to their full strategic potential: simultaneously as launch pads for coordinated attacks and strongholds for defensive support. The key principle to keep in mind when attacking and defending is to play away from thickness. A stone played too close to your opponent’s thickness will make the former an easy target for attack, while playing too close to your own wastes its potential and makes you overconcentrated. Instead, aim to drive your opponent toward your thickness, using it as a shield against which to break their offense.

At its core, fighting is about balance: Attack and defense as two functions of the same move. A prepared attack naturally reinforces your own position, while a solid defense can quickly shift to a counterattack. The aim is not to kill – killing is merely a happy consequence of solid play – but to pressure the opponent into disadvantageous positions and inefficient shapes.

Helpful Links:

How to Think During the Middle Game in Go

Are You Attacking, or Being Attacked?

Making Shape

In Go, shapes are the recurring patterns formed by the interaction of same-colored stones in relation to nearby enemy stones. The goal of the game in terms of shape is to connect one’s position as solidly as necessary – but no more – using as few stones as possible. In essence, proper shape is the local expression of the efficiency principle: deploying one’s forces effectively in space and time to gain a tactical advantage.

To beginners, the principles that determine good and bad shape often appear vague or mysterious, which may lead to the assumption that years of study are necessary to gain any meaningful understanding of them. While it does take time to cultivate the aesthetics of proper shape and apply them elegantly in one’s play, the core idea is straightforward and easy to grasp: Vital points – the key, multifunctional joints of a position that stabilize, connect, and expand it while maintaining flexibility and exerting influence all around it. By occupying and protecting these points, good shape emerges organically: Stones are alive, connected, and serve the dual purpose of reinforcing our position while applying pressure on the opponent in accordance with the golden principle “The enemy’s vital point is your own.” At every stage of the game – whether expanding or limiting territory, connecting or cutting a group, creating or destroying eyes – the move that’s best for your opponent is often the best one for you too, and taking it will strengthen your shape while leaving theirs thin or overconcentrated, short on liberties, with insufficient eye space to live.

As beginners with a limited intuition of what constitutes proper shape, the most reliable way to achieve it to evaluate each shape move through the lens of three simple questions:

- Does it connect my position efficiently?

- Does it create or protect eye space?

- Does it pressure the opponent?

Moves that satisfy at least two of these criteria tend to form the strongest, most efficient shapes.

Helpful Links:

The Dance of Bad and Good Shapes

Essential Middle Game Tactics

Here are some practical fighting tips to consider at all stages of play, but specifically in the middle game where the bulk of the conflict arises. Adding these to your tactical toolkit will greatly sharpen your combative instincts:

Attack from a distance: Weak stones should be approached rather than touched directly. Contact moves strengthen your opponent by forcing solid responses.

Defend by attaching: Conversely, when your own group is weak or under attack, attach to enemy stones. This will force local exchanges that help stabilize your position.

Play forcing moves before defending: Before automatically responding to a threat, look for sente moves locally or elsewhere that your opponent must answer to prevent unacceptable losses. You can then defend under improved conditions.

Always connect against a peep: Peeps threaten to cut and disconnect your stones, and ignoring them is almost always disastrous. “Even a fool connects against a peep.” -9-dan master Kageyama Toshiro.

Don’t peep where you can cut: Peeping at a cutting point allows your opponent to connect their position, essentially offering them a “thank you” move.

Cut first, think later: When your opponent leaves a cutting point, it’s often best to take it immediately. Cutting separates their stones and creates attacking opportunities that could lead to considerable profit in the long run. Cut now and read out the continuations later.

Capture your opponent’s cutting stone(s): Cutting stones are usually the key stones for both sides in an ongoing fight. Capturing them settles the local position in your favor and often weakens or even collapses your opponent’s positions elsewhere.

Capture ladder stones as soon as you can: If your opponent plays into a losing ladder, capture as soon as there is nothing more urgent on the board. Waiting gives them time to create ladder breakers or complicate the fight in other ways.

3. Endgame

When major conflicts subside and the largest groups have been settled, the focus of play shifts to the yet-unresolved borders of territory, and we enter the third and final stage: the Endgame. Attack and defense remain deeply relevant here, but rather than serving broad strategic goals, their purpose is immediate and concrete: to secure the most points by solidifying your territory and reducing the gains of your opponent. This is where the ability to quickly count how many points a move gains you – and prevents your opponent from gaining – often determines the final outcome.

Because the Endgame is the most calculation-heavy stage, its deeper study typically begins at the higher kyu levels, once players have developed the reading and counting skills necessary to evaluate the more subtle Endgame exchanges. Nevertheless, even a basic grasp of point calculation can sharpen your positional judgment and dramatically improve your closing play.

Helpful Links:

A Game of Initiative

The other critical factor that determines the overall value of a move beyond its raw point count, is whether it secures the initiative – sente. Gaining and keeping sente is one of the central directives of Go (see Whole-Board Thinking), and often the decisive winning factor in a game.

Broadly speaking, all moves fall into two categories: sente moves, which force an immediate response from the opponent, and gote moves, which conclude the local exchange and allow them to redirect the play elsewhere.

Ideally, we want to finish every local exchange in sente. However, depending on the situation, a gote move may be necessary to secure a vital shape point or stabilize an important group. It’s the skillful balancing of sente and gote moves to maximize gains without leaving weaknesses that transforms your endgame from a desperate scramble into a disciplined, deliberate closing act.

Helpful Links:

Endgame Checklist

Here is the general order of priority to follow when choosing endgame moves, based on their conferred initiative:

- Double sente: Sente for you and for your opponent – These are the highest-priority moves on the board and should be taken immediately, as they secure points while denying the opponent the same.

- Sente: Sente for you, Gote for your opponent – These moves force a response and let you keep the initiative. Aim to chain together as many sente exchanges as possible, starting with those that yield the largest territorial gain or follow-up moves.

- Reverse Sente: Gote for you, Sente for your opponent – When no more sente moves remain for you, look for gote plays that neutralize your opponent’s sente. These are rare, as the sente is usually taken before the reverse sente becomes profitable.

- Gote: Gote for you and for your opponent – These are the final moves of the game that solidify borders and claim the last available points. Play them last, beginning with the largest.

Conclusion

Every game of Go is a personal journey through shifting landscapes of intangible thought. In the beginning, it unfolds as a vast strategic expanse – endlessly abstract and brimming with potential. As stones multiply and positions collide, the terrain morphs into a dynamic field of fierce tactical struggle. By the final moves, the board has been transformed from mere ideas in the mind into a tangible tapestry of living territories.

Each stage of the game builds upon the last: The Opening establishes the balance of influence, the Middle game challenges and refines this balance, and the Endgame converts it into measurable values. Viewed as a whole, the three stages of the game flow naturally from the broad brushstrokes of strategic planning to the incisive thrusts of tactical execution. Yet at every stage, both remain indispensable. Without sound strategy, tactics have no purpose; Without sharp tactics, strategies are merely castles in the air.

But to develop true strength in this inseparable combination of Strategy and Tactics, one must go above and beyond the actual moves played at the board. Meaningful improvement – more than just a few stones – comes from deliberate study and the practical application of learning in one’s own play. In the next article, we’ll explore how to train effectively off the board and build a practice routine that drives consistent, long-term progress.

Stay tuned, and keep sente.

Great article! A lot of info explained short and sweet!

Thanks Francisco!